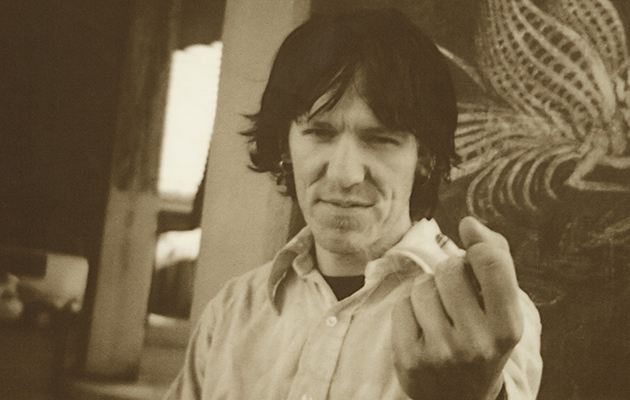

Elliott Smith may have been a romantic, after a fashion, but it seems unlikely he would have chosen to be memorialised as a tragic hero. “I don’t want to perpetuate the notion that if somebody plays music they must be fucked up or crazy,” he told me in Austin in March, 2000. “I don’t think...

Elliott Smith may have been a romantic, after a fashion, but it seems unlikely he would have chosen to be memorialised as a tragic hero. “I don’t want to perpetuate the notion that if somebody plays music they must be fucked up or crazy,” he told me in Austin in March, 2000. “I don’t think it’s glamorous in the least. It winds up being another part of your cartoon costume, because then it’s supposed to stand in for actual life.”

In Smith’s short life and brilliant music, opposites often seemed to be pitted against one another, not least the strains of romance competing for traction with a heartfelt scepticism. While that latter instinct could have self-sabotaging consequences, it also made Smith fiercely cynical about rock mythologies and martyrdoms. He wrote about dependency and fragility out of something akin to journalistic accuracy, not for transgressive cachet.

It’s worth remembering this, nearly 14 years after Smith’s likely suicide, as a deluxe edition of his finest album looks destined to be greeted not just with acclaim, but with the full gamut of doomed poet clichés. “Either/Or Reissue Shines New Light On Tormented Singer Elliott Smith,” read a headline on the New York Times website as the 2CD set was announced and, in fairness, it’s easy to accentuate the negative: the intimations of mortality on every album stretching back to his solo debut, 1994’s Roman Candle; the fatalism intertwined with his beautiful melodies. “When they clean the street,” he sings on “Rose Parade”, “I’ll be the only shit that’s left behind.”

I first met Smith in spring 1998, as Either/Or was being belatedly released in the UK, and he was sweet, funny, solicitous, and not quite as shy as his increasingly formidable reputation suggested. With a similarly unexpected candour, he was swiftly talking off the record about how he’d been institutionalized a few months earlier. At his side was his former girlfriend, Joanna Bolme, who had come along to London to look after him. Smith’s career was blooming, with a recent Oscar nomination for Best Song, a major label debut (XO) in the works, and a move from the hometown security of Portland, Oregon, to New York. In the midst of such upheaval, he seemed to require significant care and reassurance.

But, as Bolme says in Autumn de Wilde’s book, Elliott Smith, she and her friends always saw Smith as a practical, capable man; “A smart guy, not just some creative genius… He could do all sorts of other shit. He was a really well-rounded person. When he started being surrounded by fans and people who would do everything for him, he lost that need to use the part of his brain that could figure things out or be organized.”

Such complexity, an unstable blend of strength and insecurity, is key to understanding Smith’s work, and Either/Or in particular. The album title was borrowed from Søren Kierkegaard’s Either/Or: A Fragment Of Life (1843), and it’s easy to find clues in the original text – “If you hang yourself, you will regret it; if you do not hang yourself, you will regret it” – that reinforce a certain dark perception of Smith. But while the Danish philosopher may have alluded to suicide, his existential point was more sophisticated; about how, whatever dilemma one faces, it’s hard to be satisfied with any binary option. “The true eternity,” Kierkegaard continues, “lies not behind either/or but ahead of it.”

Smith probably never reached that point of transcendence, but his Either/Or can be interpreted as a determined attempt to try and get there. While his previous two solo records had been seen as adjuncts to the career of his substantially rockier band, Heatmiser, now it became apparent that this music – a silvery, whispered folk-pop, always more ornate and complicated than it was given credit for – should be his main focus. For all the protests of self-deprecation, it’s the sound of a singer-songwriter clearly aware that his gifts demand a bigger stage. The reissue credits list the houses in Portland where these songs were first recorded, but at the same time Either/Or acts as a farewell to that city, and to home recording.

One of Smith’s old Portland associates, Larry Crane, has remastered the dozen songs on Either/Or, scurfing off some of the lo-fi muffle and adding new zing to, for instance, the steady clip of the drums on “Alameda”. It’s a process of clarification that tends to enhance the album’s air of intimate engagement instead of diminishing it, while at the same time pointing up the fact that, albeit on a tiny scale, Either/Or’s songs are meticulously arranged confections. XO and Figure 8 might have expanded Smith’s canvas, but the likes of “Angeles” are already elaborately layered masterpieces of folk-baroque.

“It was just absurd,” co-producer Rob Schnapf told Pitchfork for an excellent oral history in 2013. “The guitar stuff isn’t even easy. It was ridiculous that he was able to just nail a vocal and guitar performance live, and he was able to double it live again…. It sounds so natural, and so simple — then you try to play it.”

Understated virtuosity proliferates on this expanded set. If anything, a solo version of “Angeles”, one of five live performances from the Yo Yo A Go Go Festival in Olympia, 1997, is even more intricate than Schnapf and Tom Rothrock’s studio take. Similarly, an alternative version of “I Don’t Think I’m Ever Gonna Figure It Out” (the original cropped up as the B-side to “Speed Trials” in 1996) is so adroit in its fingerpicking one suspects Smith would have enjoyed comparisons with John Fahey, had his taste for Beatlesy toplines not masked those folk-blues foundations.

Beatlesy toplines, of course, provided an entrée into the mainstream, and “Angeles” itself, along with the palpably angry “Pictures Of Me” (an indication, along with the spiralling “Cupid’s Trick”, of where Smith’s sound would go next), capture a songwriter railing against the vicissitudes of fame before they have even impacted on him. Again, though, there’s a hint of ambiguity about what kind of career he really wants: “All your secret wishes could right now be coming true,” he sings in “Angeles”, alluding to his own covert ambitions hidden beneath so much indie-rock contempt.

“Say Yes”, meanwhile, is melodically all lightness and charm – a McCartney hovering on the safe side of whimsy – while simultaneously graphing out the end of Smith’s relationship with Joanna Bolme. The prognosis on love seems gloomy – “Situations get fucked up and turned around sooner or later” – but the duality is there once more, as Smith ends the album at least trying to assert how the relationship has made him a better person: “Now I feel changed around and, instead of falling down,” he claims, “I’m standing up the morning after.” “I wish the circumstances in which it was delivered were a little bit more ideal,” Bolme would note, ruefully, in the 2014 documentary, Heaven Adores You.

“Everybody pretends they’re more coherent so that other people can pretend they understand them better,” Smith said in 2000. “That’s what you have to do. If everybody really acted like how they felt all the time, it would be total madness.” Either/Or takes that principle of emotional inconsistency, and turns it into a symphony of mixed messages. The theme extends into the second CD of this 20th anniversary edition, featuring plenty of gorgeous music that shouldn’t be underestimated as marginalia. A Yo Yo A Go Go live version of the unreleased “My New Freedom” presents the aftermath of his relationship with Bolme in less mediated and much more bitter terms than on “Say Yes”.

“I Figured You Out”, meanwhile, is a critical discovery, dating from 1995: Smith’s demo for a song he gifted to another Kill Rock Stars artist, Mary Lou Lord, for her “Martian Saints” EP (1997). Recorded at the Heatmiser house, with that band’s Neil Gust on drums, it still sounds like a fully-arranged, finished piece of work, notable for a wheezing organ carrying the lovely melody rather than the acoustic guitar. There is also a first stab at “Bottle Up And Explode”, which eventually appeared on XO (1998), featuring an unlikely synth line, a slightly wobbly pace and completely different lyrics in which the theme of frustration seems to be targeted at the cold, claustrophobic environs of Portland: “Everything around here happens so slow.”

Once “Bottle Up And Explode” finishes, the album ends with a brief reprise of “Pictures Of Me”, rescored for fairground organ. How should we understand such a version, after all that has gone before, and after? As a sarcastically jaunty way for Smith to articulate his hatred for showbusiness? Or as a cute, goofy exploration of musical possibilities – an innocent pleasure, from a man whose legend would mitigate against him having such things? The true answer, perhaps, lies not behind either/or, but ahead of it…