On the evening of February 9, Robin Pecknold ambled into one of those strange controversies that blow up on social media and, for a few hours, consume the music world’s chattering class. Talking to the Dirty Projectors’ Dave Longstreth on Instagram, Pecknold became embroiled in a droll, quasi-academic discussion about the precarious state of (his quotes) “indie rock”. “I feel,” he wrote, “like 2009, Bitte Orca/Merriweather/Veckatimest, was the last time there was a fertile strain of ‘indie rock’ that also felt progressive w/o devolving into Yes-ish largesse.”

Opprobrium, inevitably, was swift. Pecknold’s comments were taken as a lament for a time when records by Dirty Projectors, Animal Collective, Grizzly Bear – and, by extension, Fleet Foxes – had greater cultural traction. In the mainstream nowadays, it tends to be R&B, hip hop and pop that are feted for an experimental as well as a commercial imperative. Pecknold’s argument was more nuanced than soundbites allowed, but it was disseminated as if he were yearning after some halcyon era, when groups of largely diffident American boys – often bearing guitars, often his friends – became stars, after a fashion.

Plenty of “progressive indie rock” is still being made in 2017, but not many debut albums of the stuff are selling 600,000 copies in the UK alone. That was what “Fleet Foxes” achieved in 2008, even while Pecknold, his bandmates and peers defied expectations of how a popular band should present themselves. They were human and unassuming, bookish and allusive, unencumbered by rock braggadocio and averse to showy press quotes. Perhaps, at times, they were also a little twee.

How, then, do we take the return of the Fleet Foxes six years after “Helplessness Blues”, at a time when their enduring aesthetic could be seen as relatively quaint, at least in mainstream terms? Unlike Pecknold, 2017’s most prominent “indie-rock” standard-bearer has correctly calculated that he will game most publicity with an agenda of snark, controversy and the most archly debauched posturing. That Father John Misty – “Elton John singing Comment Is Free pieces,” as one Twitter observer described “Pure Comedy” – once occupied the Fleet Foxes drum stool is just one more irony for his wearyingly vast collection of them.

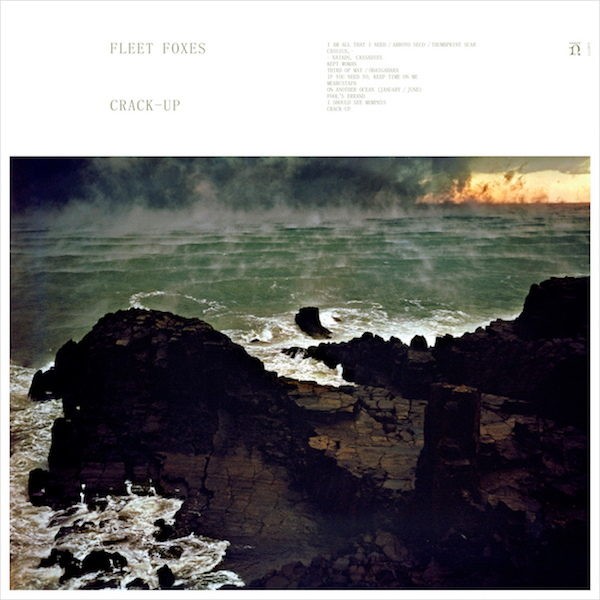

While Misty assiduously courted the headlines, Pecknold made a tactical retreat. He pursued a degree at Columbia University in New York and, he told Reddit in May 2016, “got some academic pretensions out of my system that I won’t be inflicting upon the listening public through song.” This, it turns out, is something of a fib. “Crack-Up”, the third Fleet Foxes album, is both elaborate and earnest, picking up roughly where “Helplessness Blues”’ “The Shrine/An Argument” left off. Songs are burdened with multiple movements and knotted titles. Classical allusions and logophilia are rampant, so much so that Pecknold seems to be in a competition with his old touring mate, Joanna Newsom, to deploy the most obscure reference: she says “Sapokanikan”; he says “Mearcstapa” (It’s the name of a monster in Beowulf, translated as “border-walker”). Track One alone has three titles (“I Am All That I Need/Arroyo Seco/Thumbprint Scar”) and, over six and a half minutes, features chromatic bells and bird song, a significantly creaking door, a clanging instrument used in Moroccan gnawa rituals called a qraqeb, a faintly eastern-sounding string section, and a sample of a high school choir singing the Fleet Foxes’ formative hit, “White Winter Hymnal”.

In the midst of all this, the old stereotype of Fleet Foxes as bucolic fabulists, peddling a hygienised vision of log-cabin folk-rock, feels almost comically inaccurate. And yet, even as Pecknold and his right-hand man, Skyler Skjelset, pile more and more esoteric detail onto each song, the fundamental charms of their band shine through. The heart of “I Am All That I Need/Arroyo Seco/Thumbprint Scar” is still Pecknold and a buccaneering acoustic guitar, leading his bandmates in sacred harp harmonies that retain all the ravishing prettiness of the original “White Winter Hymnal”. Crack-Up might be a record about flux and contrast, as musical and lyrical ideas clash and mutate, and repeated images of city and ocean roll into one another. But Pecknold’s sweet and tentative air remains constant even when he is trying to articulate how he has changed. “I know you’ll be/Bolder than me/I was high, I was unaware,” he sings over the rustic systems ripple of “Kept Woman”.

Pecknold, in fact, is at times chronically self-aware. He recently described the shifting terrain of “Third Of May/Ōdaigahara” as beginning like “Fleet Foxes: Phase One” – “happy, upbeat, sunny” – and passing through “glimmers of doubt”, a “super fraught and tense” passage with “glimmers of hope”, and a “final defeat” before “it just floats away into a beautiful nothing”. Ōdaigahara, for the record, being a mountain in Japan, and Japan being where Fleet Foxes concluded their last tour, in 2012. Embedding a meta-narrative about the history of your band into one song, even when that song is nearly nine minutes long, seems a bit of a stretch. But “Crack-Up”’s filigree constructs are a lot more robust than they first appear, and no amount of ornamentation – the harpsichords! the autoharps! – or conceptualising can imbalance the essential loveliness of these 11 songs.

For a record that expressly strives to present a mature band, Pecknold and his bandmates’ industry can be easily mistaken as sophomoric, driven by a neurotic need to be respected as eclectic and ambitious. But satisfyingly, the multiple gambles and expansions almost all pay off. A jazzy little guitar solo among the swells and buffets of “Mearcstapa”? A random clip of an old Mulatu Astatke record at the end of “On Another Ocean (January/June)”? A free squall of horns in the climactic title track? Every one of them makes sense in the enveloping 56-minute patchwork.

“Crack-Up” hardly aspires to be a withering commentary on art and the world and how the two intersect in 2017. It is, though, distinctive, involving, challenging, accessible, “progressive” and most other things that continue to be desirable in an indie-rock record, whatever the year. A recipe for total entertainment forever, you could say, if you were being fashionably edgy.