1240: By the entrance to Somerset House on Waterloo Bridge, there is a shop called Knytta, where one can "create your own unique jumper and see it made in front of you." It is near here, on a bright and invigorating January day, that about 40 people wait to be summoned down into the basement. PJ Ha...

1240: By the entrance to Somerset House on Waterloo Bridge, there is a shop called Knytta, where one can “create your own unique jumper and see it made in front of you.”

It is near here, on a bright and invigorating January day, that about 40 people wait to be summoned down into the basement. PJ Harvey’s “Recording In Progress” project started on Friday, with publicity and early reports suggesting a kind of art installation, where Harvey and her band work on an album as a rock analogue to a Marina Abramovic performance piece: sealed behind glass, unable to see the fans watching, with self-consciously suppressed excitement on the other side.

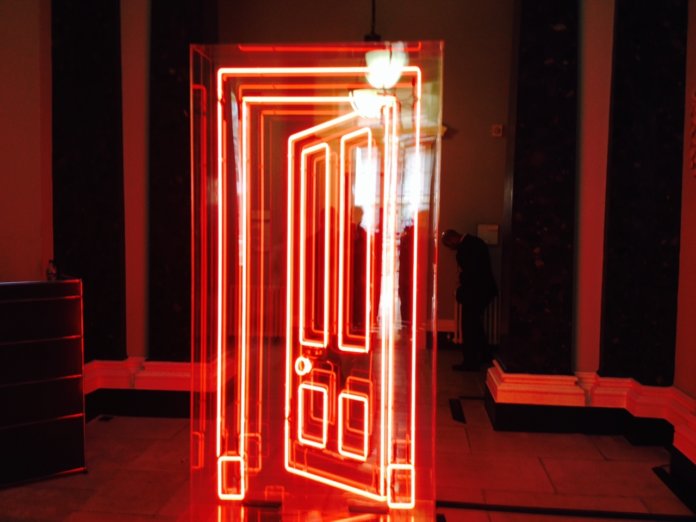

1245: We are admitted, past a glowing door sculpture, into a grand anteroom, smelling of paint. Here you can buy postcards (£1.50), signed posters (£25; not a bad deal), and photographs by Harvey collaborator Seamus Murphy (£300). Lyric sheets are £50 each. Here, also, handing in phones, cameras and any other electronic recording devices is a necessary protocol: PJ Harvey’s openness, reasonably enough, has its limits.

To emphasise the aesthetic of an art event, rather than a musical one, there are programmes, containing an interview with Harvey by Michael Morris, co-director of Artangel. They talk a good deal about the significance of place, and the history of Somerset House: about how Oliver Cromwell’s body lay in state there; about how the stone it was built from comes from the Jurassic coast, near Harvey’s birthplace; about how the Thames runs underneath the building. There is some discussion, not for the first time regarding Harvey, of “water and death”, and Morris – who had heard demos of the songs at time of writing – reveals the putative album to be a “much broader, more geopolitical record than Let England Shake”.

“This cycle of songs considers the major issues of our time,” he notes, “social inequality and injustice, the politics of poverty, anxiety and paranoia about terrorism and the way that hate breeds hate among generations in opposition.” Money, it will transpire, gets everywhere.

1300: Artangel curators lead us behind a restaurant and down into the lower levels of Somerset House, towards a room that was, in a previous life, the Inland Revenue’s staff gymnasium. Eventually, we reach a door that reveals steps down towards the gymnasium/studio itself. Feedback and martial drums greet us: suspicions that the musicians might be eating their lunches prove surprisingly unfounded.

At the bottom of the steps is a glass case displaying instruments. Then, turning left, we are in the viewing gallery. Two sides of the studio are glass (though the performers cannot see out), and it is easy to wander around and catch them – Harvey, producer Flood, John Parish, Terry Edwards, drummer Kendrick Rowe and two techs/engineers, plus a photographer I assume is Seamus Murphy – from a multitude of angles. There is a heraldic crest for PJ Harvey on the wall and on a marching band bass drum, the shield supported by a goat and a two-headed dog.

Edwards is playing flute, heavily distorted. Parish is hunched over a National Steel guitar. Rowe is stood up, playing two snares. Flood is sat on a white sofa. Harvey, meanwhile, is surrounded by saxophones, dulcimers and a small mixer, blowing her nose.

1303: The song restarts, and this time Harvey is singing: “God sent you” seems to be a frequent refrain. Framed copies of lyrics in progress are mounted around the walls, though none seem to correspond with what I can make out she’s singing. The number of musicians is sparse, but the sound is dense and frictional; “Is This Desire” might be the closest comparison, though it may also be a mistake to draw comparisons at this early stage (perhaps a reason why Artangel only issued review tickets to art critics rather than music ones).

It is, though, a short and instantly excellent song, and one whose catchiness will become apparent in the next 45 minutes. Harvey’s part ends with some virtuoso whoops. As it finishes, the audience almost starts to clap, then realises that such a response would be vulgar – and, of course, futile, since the performers cannot hear anything outside their space.

1306: Flood, who soon emerges as the dominant – or at least the most talkative – character, gives his notes on the take. He is not happy with Parish’s guitar part: “I don’t want to hear the guitar. I know it’s there for a guide.” There is some discussion of replacing it with a keyboard, but Parish eventually experiments with a lighter, less noisy strum. Nearby, is a table of beautiful hand percussion, and weathered, arcane instruments proliferate in the space – aesthetically pleasing objects in a fairly blank and functional room. Harvey is stationed well away from the glass – no-one can read her lyrics and notes over her shoulder – and is close to a gorgeous old upright piano.

1309: One of the engineers appears to be giving, under Flood’s tutelage, names to each take, and this one is “Brian Take”; a significantly demystifying moment, really. It’s at this point that the reality of what we’re seeing crystallises. It’s not like watching animals in a zoo, and it’s not much like an art installation, either. The weirdness of the setting doesn’t add any mystique to studio in-jokes, it just broadcasts them to 40 fans quietly delighted at the intimacy of their access.

Nothing here is materially that different from any other studio session I’ve attended, and it’s worth remembering that plenty of artists, especially in the past, have recorded albums in busy studios, full of friends, business associates, hangers-on and so forth. Myths that cluster round PJ Harvey often privilege the seriousness, intensity and privacy of what people assume is her working practice, but maybe that’s a naïve way of looking at a collective and often mundane endeavour.

And maybe that’s one of the critical purposes of “Recording In Progress”; to get rid of some of those assumptions, while at the same time ensuring that Harvey remains in control. A lot of her work can be seen as challenging her own shyness, in a mediated way, and using that as part of the artistic process; it’s a good way to look at “Recording In Progress”, anyhow.

1310: Harvey rubs her sides; it’s possibly chilly in there. Another take begins, and with Parish’s noise reduced, Edwards’ flute rises to the fore; looping and scuffy, reminiscent of how Florian Schneider played on an early Kraftwerk track like “Ruckzuck”. Flood approves. “Gregory take”.

1313: Another similar take. Still sounds great. Flood encourages Edwards to concentrate on the “rhythmic side of things”. Edwards says something about “distorted ska”.

1317: And again. Not bored of it yet. The strength and clarity of Harvey’s vocal is uncannily consistent and, while she allows Flood to do most of the talking, her constant alertness, the way she turns precisely to look at whoever is talking, is striking. As the session goes on, what initially appears to be passivity slowly reveals itself to be a more quiet, considered, collaborative, discreetly authoritative way of working.

This time, Flood is interested in working on the beats. “Let me experiment,” says Parish, wryly. Flood talks about loops, and tells Harvey “I’m even singing a bassline in my head.”

1322: A tech rigs up another snare for Parish, then he and Rowe play for a while together. I walk around to the other side of the room and copy down what appear to be song titles on a wallchart: “River Anacostia”, “Medicinals”, “Chain Of Keys”, “Near The Memorials To Vietnam And Lincoln”, “A Dog Called Money”, “The Ministry Of Social Affairs”, “The Age Of The Dollar”, “The Community Of Hope”, “The Wheel”, “Homo Sappy Blues”, “Imagine This”, “The Ministry Of Defence”, “The Boy”, “A Line In The Sand”, “Dollar Dollar”, “I’ll Be Waiting”, “The Orange Monkey”, “Guilty”.

1326: Parish and Rowe play their interlocking martial rhythms over the top of a recorded take. While her recorded voice plays, she pulls comically aggressive faces at Flood and bends her knees in time to the beat. Flood is increasingly taken with the rhythm and wants to do another overdub.

1329: Another dual drummer take. I wander over to the window. About 20 feet above, I can just see people heading over Waterloo Bridge.

1331: PJ Harvey yawns.

1332: Flood instructs Parish and Rowe to switch kits and both play Parish’s part. This time, Edwards nonchalantly picks up a melodica and honks along, disconsolately. Flood is impressed, and gives him a thumbs-up. “Are you playing a note or just breathing?” Edwards honks again, disconsolately. “It’s nicely out of tune,” he says.

1335: We’re off again. Harvey fiddles with her mixer as Edwards’ melodica wanders back into the mix. She picks up a sheet from her music stand and makes a note. “It’s starting to sound pretty interesting now,” she says, approvingly. “How’s the song going?” asks Flood. “I don’t know where the song is,” she laughs.

Flood, though, is energised, even if he hasn’t moved from the sofa, and is keen on how things are “atonal but tonal”, and how it’s important for him that it avoids slipping into the blues. There is a suggestion Harvey adds a bass clarinet line.

1340: Instead of the clarinet, Harvey picks up her tenor saxophone while the tech fixes her mic. She begins to warm up.

1341: Terry Edwards stares directly into the glass with an air of profound suspicion. It becomes apparent, though, that he’s adjusting his headphones in the mirror. Flood hunches over a guitar while Harvey blows experimentally, eventually matching her tone to that of Edwards’ melodica.

1345: The band are on the verge of running again, when the sound cuts out, and we’re ushered out of the studio space.

“You’ll witness something that is passing in real time,” Harvey says in the programme interview, “and I feel that the best part of any creation is the creating itself. That is when it’s most vital, most exciting…”

Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey