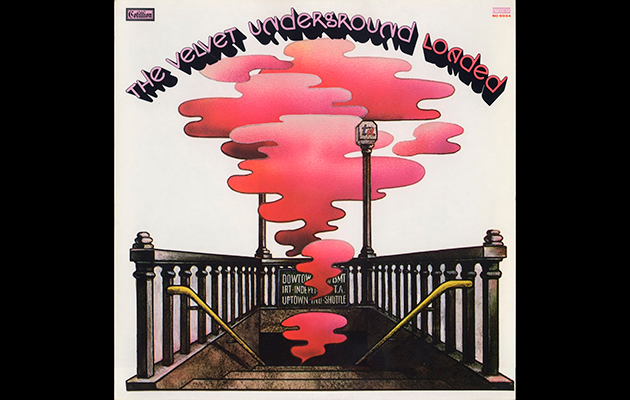

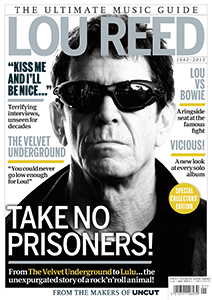

Following yesterday's news that the Velvet Underground's Loaded is to due a posh six-disc anniversary reissue, I thought I'd dig out my review of the album that originally appeared in our Lou Reed: Ultimate Music Guide. It's funny, the older I find myself coming round to the idea that the Velvets we...

Following yesterday’s news that the Velvet Underground’s Loaded is to due a posh six-disc anniversary reissue, I thought I’d dig out my review of the album that originally appeared in our Lou Reed: Ultimate Music Guide. It’s funny, the older I find myself coming round to the idea that the Velvets were a better band after John Cale had left and – whisper it – I even quite like Squeeze…

Incidentally, you can find interviews I conducted for the anniversary reissue of the third Velvets album with Doug Yule and Moe Tucker by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner

——–

Looking back on the circumstances around his departure from the Velvet Underground, Lou Reed had this to say in 1972: “I gave them an album loaded with hits and it was loaded with hits to the point where the rest of the people showed their colours. So I left them to their album full of hits that I made.” The recording of Loaded was clearly an emotional time for Reed. The period between the March 1969 release of The Velvet Underground and the start of Loaded’s principal recording sessions in April 1970 was especially fraught for the group. They began work on a fourth studio album in May, 1969. But by August, the band had parted company with MGM – new MD Mike Curb envisaged a more wholesome direction for the label, and suspecting how that might pan out the for his charges, manager Steve Sesnick extricated the group from their contract. By November, the album had disappeared. Reed, meanwhile, was having problems of his own. His long-running affair with Shelley Corwin, his muse, was in a slow decline. Increasingly disturbed by the effects of long-term drug use on close friends including Factory compatriot Billy Name, Reed responded by getting even more out of it. “Lou went out of his skull and ended up with a warped sense of time and space that lasted several weeks,” journalist Richard Meltzer is quoted by Reed’s biographer, Victor Bockris.

At the start of 1970, the Velvet Underground signed to Atlantic Records, while still $30,000 in debut to MGM. Moe Tucker, meanwhile, took maternity leave in March; her stand-in was Doug Yule’s younger brother, Billy. Existing frictions between Reed and Sterling Morrison continued. “I had hardly spoken to Lou in months,” Morrison admitted to NME’s Mary Harron in 1981. “Maybe I never forgave him for wanting Cale out of the band. I was so mad at him, for real or imaginary offences, and I just didn’t want to talk. I was zero psychological assistance to Lou.” Elsewhere, other equally toxic dramas were being played out. Writing in The Velvet Underground fanzine in 1996, Doug Yule revealed, “Sesnick, always looking for the advantage, was driving wedges between everyone, trying to keep the bickering going and the communication between us shut off.”

By the time the Velvets convene to record Loaded, you could be forgiven for wondering whether they’d actually finish the album, or simply combust in the studio. The April to July sessions at Atlantic Studios, New York overlapped with a ten-week homecoming residency at Max’s Kansas City. Reed, worried about his straining his voice, ceded four lead vocals to Doug Yule. “The sessions for Loaded were extremely different than those which produced the third album,” Yule wrote. “Many of the songs had been played live, but the recorded versions were very different than the road versions. The emphasis was on air time. Every song was looked at with the understanding that there was a need to produce some kind of mainstream hit… Songs were built intellectually rather than by the processes that live performances brought to bear, instinct and trial and error.”

The songs – including their roll call of ladies: Jane, Ginny, Miss Linda Lee, Polly May and Joanna Love – represent a refinement of the band’s aesthetic – a healthy middle ground between the avant garde stylings of the first two albums and Reed’s Top 40 sensibilities. And such variety! From jaunty, Monkees style pop (“Who Loves The Sun”) to freewheeling rave-ups (“Oh, Sweet Nuthin’”). And then there’s “Sweet Jane” and “Rock & Roll”. The former, with its sensational ‘D-A-G-Bm-A’ hook, finds Reed on familiar territory, “Standing on the corner / Suitcase in my hand”, watching Jack and Jane, two straights: a banker and a clerk. Reed describes the differences between male and female, conservative and liberated, old and new, shifting perspectives as the song progresses, double backing on himself, wrong-footing the listener. It’s an immense and highly complex piece of narrative songwriting, followed by “Rock & Roll” – one of the great songs about the transformative power of music. Possibly autobiographical, it’s about five-year old Jenny, who “one fine morning turns on a New York station and she doesn’t believe what she heard at all.” Her “life is saved by rock and roll” and she is elevated to the ultimate Reed condition: “It was alright”.

“Cool It Down” is more up-tempo pop, this time with a Stonesy barroom piano, before “New Age” – another example of Reed’s next level song writing on this album. A love song of sorts – delivered by Yule – full of tender nostalgia for a “fat blond actress… over the hill now / And you’re looking for love”. But the real thing here is the song’s audacious three-act structure, beginning with the verses, rising at 3:08 to what you assume is the outro and then slipping in a majestic middle eight at 3:32 to lead you out of the song across the next minute and a half. “Head Held High” is a fun stomping boogie followed by the almost comically jaunty “Lonesome Cowboy Bill” and the beautiful “I Found A Reason” which walks a line between the doo wop so beloved by the young Reed and the stoned balladry of “Pale Blue Eyes”. The pace quickens with “Train Round The Bend” draped in eerie swathes of tremolo, before we reach the album’s hymnal-like closer, “Oh, Sweet Nuthin’”. Step forward Sterling Morrison, who delivers some fine intuitive guitar playing here opposite Reed: whatever issues they might otherwise have had, they operated entirely in synch here as Morrison’s loose, rolling guitar chords sit perfectly against Reed’s wide-ranging solos. Credit, though, is also due to Doug Yule: an accomplished multi-instrumentalist, whose work here – on bass, piano, guitar and vocals – provides a consistently solid bedrock for Reed’s flourishing songwriting.

Lou Reed left the Velvet Underground on August 28, 1970 after the final show at Max’s, leaving New York for his parents’ home in Freeport, Long Island. The strain had become too much for him. In his absence, Sesnick meddled with Loaded: he cut the “wine and roses” bridge section from “Sweet Jane”, trimmed back the ending to “New Age” and messed with Reed’s intended sequencing. Further, he shunted Reed’s name below Yule and Morrison on the band line-up for the album’s original pressing, and attributed the songwriting credits as: “All selections are by The Velvet Underground”. It took a subsequent court case to restore Reed’s full rights to all the material.

While Reed spent 1970 and 1971 in exile, Yule ploughed on with the Velvet Underground, fulfilling dates in Europe. It was a dismal end – their explosive promise fizzing out in European backwaters during the early Seventies, the corpse growing cold somewhere between Kingston Polytechnic and Northamptonshire Cricket Club. A fifth album, Squeeze, appeared in February, 1973 although this was ostensibly a Doug Yule solo record (with, curiously, Deep Purple’s Ian Paice on drums).

None of this, though, can diminish the power and brilliance of Loaded. As Reed himself observed, “Despite all the amputations, you know you could just go out and dance to a rock and roll station.” The power of rock and roll conquers all. It was alright.

The History Of Rock – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – is now on sale in the UK. Click here for more details.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.