Earlier today, I spent a few minutes looking for anything I’d previously written about Leonard Cohen. One of the things I found, and had forgotten about, was a review of “Ten New Songs” from my last days at NME. There isn’t much to be proud of in the piece; a lot of pat auto-criticism involv...

Earlier today, I spent a few minutes looking for anything I’d previously written about Leonard Cohen. One of the things I found, and had forgotten about, was a review of “Ten New Songs” from my last days at NME. There isn’t much to be proud of in the piece; a lot of pat auto-criticism involving “the qualities that have inspired at least three generations of self-conscious miserablilists” and “cheesy production”. The last line, though, is kind of interesting: “Life’s a bitch and then you die, but in Cohen’s case, nowhere near as early as he imagined.”

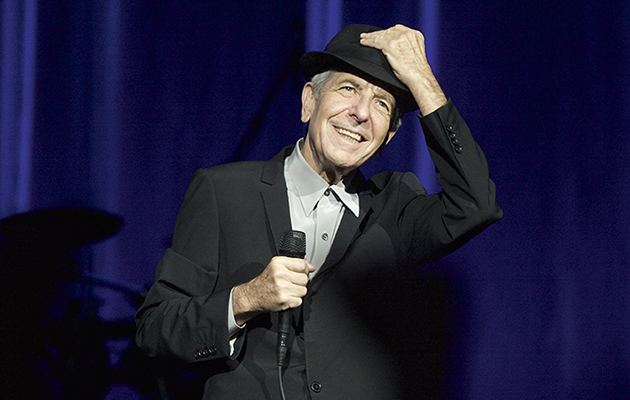

The enduring survival of Leonard Cohen – comfortably into his eighties, and some distance beyond many of his juniors, as well as his contemporaries – was a small miracle to take comfort from these past few years. It became more obvious than ever these past few weeks, as “You Want It Darker” landed in a time of such turmoil, at a time when voices of contemplative maturity, wisdom and humanity seemed in chronically short supply.

As is the modern way, and one that may well have been anathema to Cohen himself – though his epigrammatic gifts with a perfectly weighted sentence would have ruled on Twitter – I resorted to sticking favourite songs onto social media. An improbable amount of Cohen material worked almost too neatly as valedictions, so the first thing I turned to, perhaps perversely, was an instrumental, “Tacoma Trailer”, from “The Future”; a tune I’ve always loved, and which felt like the end credits music at the close of an epic, though emotionally measured, drama.

It’s a neat illustration, too, of the point made by Bob Dylan in David Remnick’s recent Cohen profile. “When people talk about Leonard,” said Dylan, “they fail to mention his melodies, which to me, along with his lyrics, are his greatest genius. Even the counterpoint lines—they give a celestial character and melodic lift to every one of his songs. As far as I know, no one else comes close to this in modern music.”

The second piece I chose was a track called “Recitation”, from the “Live In London” album, recorded at the O2 run in 2008. I’m never sure whether that’s the right title for it, given how it seems to derive from the same poem that produced “A Thousand Kisses Deep”.

Some fine things have been written about Cohen these past few days, and I don’t feel I’m ready, or maybe capable, of matching them. We’re working on what we hope will be suitable Uncut tributes for further down the line, but in the meantime, here’s the best piece from my personal archives: a review of that “Live In London” album, “an uncommonly thoughtful victory lap”…

When The Songs Of Leonard Cohen arrived in record shops just after Christmas, 1967, its creator was already 33 years old – an unusual age to be releasing a debut album. But the patina of experience was critical to Cohen’s appeal. Here was a singer – no, a poet – who could write about the usual stuff, chiefly girls – well, women – with a rueful and weathered maturity far beyond the range of his younger contemporaries.

It was a good trick then, and it remains so four decades later, as Leonard Cohen continues his extraordinary comeback tour. While the likes of The Rolling Stones tackle the songs of their youth in an absurd if bracing defiance of age, and Bob Dylan and Neil Young often seem to have an ambiguous, sometimes fraught, relationship to their back catalogues, Cohen has no comparable problems. The older he becomes, the better he inhabits many of these uncannily graceful and profound songs.

Consequently, Live In London is much more than a souvenir of a memorable show at the O2 Arena in July 2008. It showcases a (then) 73-year-old singer with still-growing wisdom and an ever-deepening voice, who now brings an even greater gravity to songs that were hardly bubblegum in the first place.

Take “Who By Fire”. It’d be risky to claim that this live reading is a more definitive version than the original on 1974’s New Skin For The Old Ceremony. But the incantatory resonance of Cohen’s baritone, the way it is underpinned so delicately by the female vocals, Javier Mas’ lute-like archilaúd and Neil Larsen’s Hammond B3, make it sound more like sacred music than a folk singer’s appropriation of sacred music, band introductions notwithstanding. An enterprising film director would do well to cast this Cohen as the voice of a god – if Cohen could reconcile the complexities of his own beliefs to accept such a frivolous gig.

Then again, as Live In London proves, Leonard Cohen is a covertly frivolous man. If he has been stereotyped for 20, 30, 40 years as the laureate of misery, these shows have redefined him as more of a droll old charmer, not averse to satirising himself.

“It’s been a long time since I stood on the stage in London,” he intones wryly before “Ain’t No Cure For Love”. “It was about 14 or 15 years ago. I was 60 years old, just a kid with a crazy dream. Since then I’ve taken a lot of Prozac, Paxil, Welbutrin, Effexor, Ritalin, Focalin. I’ve also studied deeply in the philosophies and religions, but cheerfulness kept breaking through.”

He says more or less the same every night, but the crafted wit is well worth repeating. Rehearsal does not preclude warmth, and the three months of preparation that Cohen and the band went through before the tour began last spring – down to the ad libs, perhaps – is one good reason why Live In London has more in common with a measured studio album than most live sets.

Spontaneity isn’t necessary here. Instead, meticulous control is crucial to the potency of these 25 songs, particularly in the marvellous sequence that closes the first half of the concert, running through “Who By Fire” and “Hey, That’s No Way To Say Goodbye” to a broadly celestial “Anthem”.

These are not complete reinventions: the musical director, Roscoe Beck, was imbuing Cohen’s songs with the same stately pacing, with similar Mediterranean fringes, as far back as 1988, judging by the Cohen Live album released in 1994. Now, though, there’s a shade more discretion to Bob Metzger’s guitar playing, and fewer cruise liner flourishes from Dino Soldo on the “instruments of wind”. Javier Mas, the Spanish guitarist, is an obvious star, but as the whole band take compact, jewel-like solos during “I Tried To Leave You”, it’s hard to spot a weak link.

Cohen himself, of course, may be more reliable these days, having lost his old habit of drinking three bottles of wine before a show. He has a clutch of relatively new songs, too, with two from 2001’s underrated Ten New Songs included in the London show, plus a stirring recitation of verses from “A Thousand Kisses Deep” that didn’t make the original recording. A meditation on love, memory, mortality and related topics, it’s an apposite highlight, not least when Cohen intones, “I’m still working with the wine, still dancing cheek to cheek/The band is playing ‘Auld Lang Syne’, but the heart will not retreat.”

It captures a man forced back on to the road by financial exigency – back to “Boogie Street”, he might say – only to discover that something else is driving him onwards. Perhaps that something, Cohen realised, is a chance to achieve a resolution of sorts, with both his art and with his fans. An uncommonly thoughtful victory lap, which deserves – and has received – a handsome recorded memorial.