Leonard Norman Cohen was born in Montreal in 1934 to a family of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. His grandfather was Polish, his mother Latvian and his father, who owned a clothing concern, died when he was nine. He went to McGill University and, despite an early affection for country music and a trio called The Buckskin Boys, his first love in those bohemian, beatnik days was poetry. By 1956, while Presley was recording “Heartbreak Hotel”, Cohen was publishing Let Us Compare Mythologies, his first collection of verse. By the late Fifties, he had pitched up in New York at Columbia University and his second volume of poetry, The Spice Box Of Earth, was published in 1961 just as Dylan was appearing on the Greenwich Village scene.

Cohen drifted to Europe, missing the great folk explosion and eventually settling in Greece. The search for the world’s quiet places was to become a recurring motif in his career, and, when he bought a house on the island of Hydra (where he lived on-and-off for several years with Marianne Jensen and her son, Axel, the inspiration behind “So Long, Marianne”), Cohen was met with the same incomprehension that greeted his retreat to the monastery.

“Everyone asked how I could isolate myself,” he reflects now. “This world is very alienated and lonely, but the two places I have felt least isolated are on the island and up the mountain.”

Two acclaimed novels followed: The Favourite Game in 1963, an autobiographical work about his early days in Montreal, and the ambitious Beautiful Losers in 1966, which had reviewers comparing him to James Joyce. But Cohen was restless – and, more to the point, broke. Good reviews don’t put food on even Greek tables and his books initially sold fewer than 3,000 copies. Yet he recalls the novel-writing days with affection, fulfilling his desire for order in a similar way to the regimented monastic life.

“In retrospect, writing books seems the height of folly, but I liked the life. It’s good to hit that desk every day and have your meal on the table every evening. There’s a lot of order to it that is very different from the life of a rock’n’roller. I turned to professional singing as a remedy for an economic collapse. I’d always played guitar and made up songs, and I decided to go to Nashville to get a job.”

He never got as far as Tennessee.

“I went through New York and got ambushed. In Greece, I’d been listening to Armed Forces Radio, which was mostly country music. But then I heard Dylan and Baez and Judy Collins, and I thought something was opening up, so I borrowed some money and moved into the Chelsea Hotel.”

After Collins recorded “Dress Rehearsal Rag” on her 1966 album, ‘In My Life’, he was invited to appear at the Newport Folk Festival and was introduced to John Hammond, the legendary Columbia A&R man, who had signed everyone from Billie Holiday to Bob Dylan.

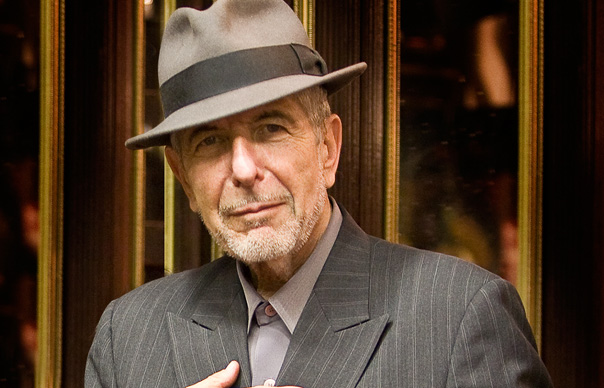

“He took me to lunch and then we went back to the Chelsea,” Cohen recalls. ‘‘I played a few songs and he gave me a contract.” That it was such a mature, assured debut is partly explained by the fact that Cohen was already 33, yet the sheer intensity of such songs as “So Long Marianne” and “The Sisters Of Mercy” took the musical world by surprise. Some of it was Dylanesque (“I walked into a hospital where none was sick and none was well/When at night the nurses left I could not walk at all”), but Cohen was a unique voice with his own literary style and a bold romantic streak to match the dark, smouldering good looks that stared out from the austere cover.

Accompanied by not much more than a nylon-stringed guitar, the confessional quality detailing highly tangled emotional relationships immediately established a huge bedsit appeal, particularly in Europe, and his debut camped out in the British charts for 18 months.

“Yes, it’s autobiographical,” he says. “I can’t just establish a narrative and fill in the characters and action in the ways some writers do, so people like Suzanne and Marianne and the Sisters of Mercy all exist. And it seems that in the manifesting of the song I have to get to what is really going on. That’s why it takes me so long to write, because I discard so much along the way.”

Cohen is full of envy for those who routinely pluck songs fully-formed out of the ether.

“The only time that ever happened to me was ‘Sisters Of Mercy’. I was in Edmonton during a snow storm, and I took refuge in an office lobby. There were two young back-packers there, Barbara and Lorraine, and they had nowhere to go. I asked them back to my hotel room – they immediately got into the bed and crashed while I sat in the armchair watching them sleep. I knew they had given me something, and, by the time they woke up, I had finished the song and I played it to them.”

It is more usual for Cohen to spend several years over a song.

“We had an intermittent friendship with Dylan for years. I don’t see him very often but we always connect in a very satisfying way and I met him in Paris a few years ago when he was performing my song, ‘Hallelujah’.

“He asked me how long it took to write, and I lied and said three or four years when actually it took five. Then we were talking about ‘I And I’, one of his songs, and he said it took him 15 minutes.”