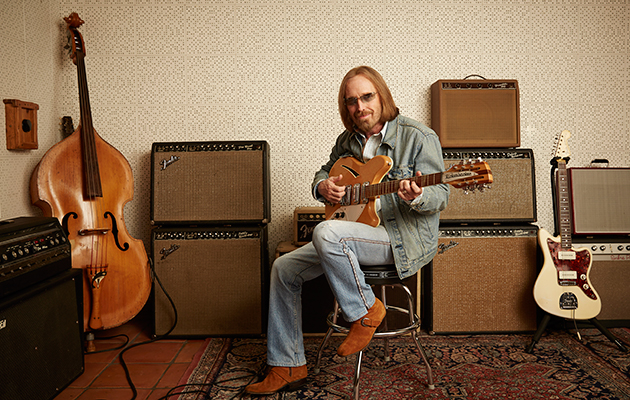

“I did go through a lot of my life with a short fuse, where I could erupt into a serious rage...” At home on his Malibu estate, TOM PETTY is reflecting on his temper, his tempestuous career with the Heartbreakers, and his urgent and essential new album, Hypnotic Eye. Petty might be calmer these ...

The unruly energy of Hypnotic Eye may have been absent from the Heartbreakers’ recorded output recently, but it has remained a conspicuous presence in their live shows. In his time onstage with the band during tours like his last UK dates in 2012 or the theatre residencies in New York and Los Angeles last year, Petty still demonstrates his love for “anything that’s rock’n’roll”, to crib the name of the song that launched them in Britain. This was in 1977, a year before they got any traction amid the surging new wave back home. Yet the albums in the latter half of Petty’s career have tended to be mellower propositions. Certainly, that was as true of such band efforts as 2010’s bluesy Mojo as it was of nominally solo outings like 1994’s Wildflowers.

But there’s no such air of late-life repose on the music on Hypnotic Eye. These songs may arrive the same year that Petty turns 64 but the best of the lot are bold, brash and gloriously loud. The opening salvo of “American Dream Plan B” and “Faultlines” is all fuzz, muscle and rumble, and even quieter songs like “Sins Of My Youth” simmer with tension. Petty’s right to marvel at its wildest moments, like the fevered vamping of keyboardist Benmont Tench, or the “ridiculous” solo by Mike Campbell on “Forgotten Man”.

“That just fries my brain,” he says, his pale blue eyes widening at the memory of hearing his bandmates attack the songs with gusto. Nor can Petty conceal the pride he feels about the album. He even admits he counts it as one of the “special ones” alongside Damn The Torpedoes, Wildflowers and Full Moon Fever. Sipping coffee from a brightly coloured ceramic mug and drawing puffs on a red e-cigarette (and the occasional real one), he settles into the sofa as he reflects on the new LP’s creation.

“The songs just started coming out that way,” he says. “This album has been made kind of in between tours and the first few tracks were done two or three years ago. They were pretty hardcore blues tracks and really great, but then I started thinking, ‘This is going down the same road twice – I’ll hold onto those for later.’ Then the songs just started determining how people were playing and the sounds they were getting. So at some point early on I started to think, ‘Let’s just do a real rock’n’roll album.’”

The Heartbreakers were down with that, to put it mildly. Speaking to Uncut, Tench says he was “really delighted” when he noticed the direction Petty’s songwriting was taking. “The material he was bringing in toward the end was much more the very, very guitar-driven stuff,” he explains. “We’ve always been a guitar band but this was more that style with hard drums and guitar riffs.”

In the keyboardist’s view, the new songs were consistent with the music that remains the Heartbreakers’ fundamental vocabulary: “the rock’n’roll of the middle-’50s and the middle-’60s”. Yet they also ended up sounding like the Petty and the Heartbreakers of the middle-’70s, too. Mike Campbell, Petty’s closest collaborator since the days of Mudcrutch, confesses he surprised the singer when he told him how much the vocals on Hypnotic Eye reminded him of his voice on the first few albums. “There was an urgency in his voice that sounded very familiar,” confirms the guitarist.

“I hadn’t thought of that, but he was kinda right,” agrees Petty with a smile. “That’s the rock’n’roll voice.”

Petty himself is given to wonder who exactly that voice belongs to now or why his signature snarl is back in the picture. “Maybe it’s an angrier, more worked-up kinda guy,” is all he’ll admit. Thanks to the singer’s affable Southern charm, it’s easy to forget what a live wire he used to be. After all, he was ornery enough to incur the ire of the music business at least twice over. On the first occasion, he declared himself bankrupt to get out of punitive early contracts on the eve of Damn The Torpedoes’ release, and then by warring with MCA over their plans to introduce a higher LP price with Hard Promises. “I did go through a lot of my life with a short fuse where I could erupt into a serious rage,” he admits. “I think that was a product of my childhood, when I had some serious abuse.”

Petty chalks up much of that darker energy to his physically abusive relationship with father Earl growing up in Gainesville, Florida. As much as it fueled his musical ambitions and bolstered his determination to stand his ground, his anger could cause considerable trouble. The most dramatic evidence came in 1984, when he vented his frustration during the Southern Accents sessions by smashing his left hand into a wall and pulverising many of the bones within. Eventually, he turned to therapy to help take the edge off the old traumas.

“I started to learn and retrace what had happened to me and why I was that way,” he explains. “It became quite clear to me why. And once you know why something is happening, you know how to fix it. Now I don’t lose my temper and, God, it’s a lot better life.”

According to Petty, the only good thing about getting old is “the wisdom part”. As he explains, “I don’t have many debates with drunks on barstools any more. That’s my shorthand for somebody who’s just a waste of time, somebody who’s just talking bullshit to me. I just walk away.”

Petty now prefers to channel the rage of his younger self into characters, guys like the pissed-off narrators of “Burnt Out Town” and “Forgotten Man”. Then there’s the youngster in the album’s opener, “American Dream Plan B”, a kid who’s “half-lit and can’t dance for shit” but is still determined to get what he can in an era of diminished expectations. Elsewhere, panic and dread colours songs like “All You Can Carry” and the album’s eerie closer “Shadow People”; clearly, this is an album that’s not just louder but darker and more despairing than many of its predecessors. As usual, the prominence of Petty’s melodic gifts and wry sense of humour are two mitigating factors.

But by their author’s estimation, the songs reflect the world as he sees it in an age of widening disparities and a public enthralled to the false values of tech and celebrity. (The album’s title refers to a camera-happy populace who barely notice they’re being controlled by the gadgets they love.) Petty leans forward to put his mug on the wide coffee table in front of him, his manner less relaxed as he mulls the state of things beyond the iron gate at the end of his driveway.

“I’m not really a political person but I am a practical one,” he reveals. “It is easy to see the good guys and the bad guys right now even though the good guys are a little grey.

“But I remember when people made a living and were quite happy and didn’t even want a swimming pool but they were fine. You could do an honest day’s work, support your family and maybe even own your own home – you could get by nicely. And as that’s been taken away, a desperation creeps in. Then you have the media trying to hypnotise them by telling them, ‘No, you should be rich or you’re nothing. If you’re not dressing like Kim Kardashian, you’re nothing.’ And that offends me.”

His laughter suggests that he’s aware of the irony of expressing these sentiments while enjoying the comforts of Malibu living, complete with a beach house closer to the ocean. But Petty still remembers what his life was like growing up in Gainesville, or driving cross-country with barely any gas money as he tried to rustle up interest in Mudcrutch. He presses one of his dark suede shoes against the table as he speaks. “I’ve been poor so whenever I hear somebody say, ‘Oh, money doesn’t matter,’ I think, ‘Well, that guy’s never been poor because that’s a stupid statement.’ But y’know, it’s nice to be able to pay your bills and not having to sweat it out all the time, because that’s most people’s lives. I don’t take that for granted. I feel very blessed and happy. But I don’t think money was ever the most important thing for us.”

Petty also understands the ultimate worth of his worries about where things are headed. “I can’t save the world,” he says, breaking up once again. “I can only bitch about it!”