How a gang of psychedelic tailors and shopkeepers changed the look and the culture of 1960s London. Tom Pinnock stitches together the story of Granny Takes A Trip, and the rock elite who shopped there. “I’ll never forget trying on some green velvet trousers,” says Kenney Jones. “The bloke sa...

How a gang of psychedelic tailors and shopkeepers changed the look and the culture of 1960s London. Tom Pinnock stitches together the story of Granny Takes A Trip, and the rock elite who shopped there. “I’ll never forget trying on some green velvet trousers,” says Kenney Jones. “The bloke said, ‘Jimi Hendrix tried them on earlier.’”

Originally published in Uncut’s October 2016 issue (Take 233)

________________________

On May 23, 1968, The Beatles opened their second boutique, Apple Tailoring (Civil And Theatrical), at 161 King’s Road, London. The store dealt mainly in the ‘regency look’ of expensive velvet jackets, and boasted a hairdressing salon in its basement. For once, though, the Fab Four were far from the cutting edge; in fact, the group were belatedly jumping on the coattails of the pioneering boutiques that had sprung up along the same corner of Kensington and Chelsea almost three years previously as psychedelia bloomed into being. Hung On You, Top Gear and Biba had all opened in 1964 and ’65, attracting debutantes, fashionistas and those too hip to rate the more mainstream Carnaby Street. But for those most in thrall to the coming psychedelic zeitgeist – musicians, artists, film stars, and the coolest followers – Granny Takes A Trip was the most important boutique of all.

“When did I start to notice clothes becoming more interesting?” says Nigel Waymouth, one-third of the team behind Granny’s, which opened at 488 King’s Road in early 1966. “Well, after we opened the shop! The Beatles had a go with their Apple store, but that didn’t last five minutes. It was the ones that started the ball rolling that are really remembered.”

“Fashion and music went together for us,” remembers Kenney Jones of the Small Faces, who were regulars at Granny’s. “We were young and impetuous, and liked the journey of discovering new things, clothes or songs.”

“We were one of the first,” says John Pearse, Waymouth’s partner in Granny’s alongside Sheila Cohen. “I guess it was a time when everything seemed possible – and it was possible, because we made it happen.”

____________________________

While British psychedelia reached its commercial zenith with the release of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band on June 1, 1967, the scene had begun flowering some years before. Drugs, of course, had something to do with it – by summer

1965, just a year after Bob Dylan got The Beatles stoned for the first time, beatnik scenesters like Nigel Lesmoir-Gordon and his wife, Jenny, were experimenting with the purest LSD available, brought straight from the Sandoz laboratory in Switzerland via Timothy Leary. What they experienced seemed a long way from the monochrome world of post-war Britain. “We were all taking a lot of LSD,” explains Lesmoir-Gordon, who later recommended David Gilmour to replace his friend Syd Barrett in Pink Floyd. “We saw a world of colour and enchantment, and we wanted our clothes to look like we felt inside. We’d seen beyond the ego. We had gone on a trip and become – you just have to buy this – one with the universe, where our consciousness expanded to fill it, and became a timeless, unified experience of love. We thought we were going to change the world, we really did.”

“We were looking for a bit of a spiritual path, I think we were seekers… fun-loving seekers,” says Jenny Lesmoir-Gordon. “I took so much acid, and it was quite pure then. If anyone came into the room you could see their thoughts. Nothing was hidden.”

The ‘teenager’ as a concept had been around since the ’50s, but many of those who reached their twenties in the mid-’60s were borne along on a wave of newly discovered optimism. “It was a great time to be young,” says Neil Innes of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, “it was empowering. We didn’t have student loans, and you never thought, ‘Can I get a job?’, it was, ‘What job shall I do?’ So young people felt they could wear anything and grow their hair long. It was a rebellion, but it was a collective narrative too, that we were gonna do this to make the world a better place.”

When producer Joe Boyd left England for the US in June 1965, he remembers beatnik culture still reigning, and his friends Nigel Waymouth and Sheila Cohen selling second-hand clothes at Church Street Market.

“It was exciting, but it didn’t feel like the world was changing,” he says. “I came back to England five months later, and London had leapt forward in a different way, of doing things, of looking… So there was definitely a big change in that summer of ’65.”

On June 11, 1965, the Royal Albert Hall hosted the International Poetry Incarnation, a chance for the capital’s beats and heads to see just how numerous others like them had become. Peter Whitehead filmed the event for his documentary Wholly Communion, and focused a lot of his attention on Jenny Lesmoir-Gordon, in attendance with her husband, Nigel.

“That was the height of everything then, when it all came together, with like-minded people,” says Jenny. “Before then, I remember someone shouting at me in the street because of my short skirt. At the Albert Hall, I was wearing a Biba dress and hat, and amazing black and white shoes. I passed one of The Who in the street once, and we just smiled ’cos we knew… You’d say, ‘He’s a head, he knows where we’re at.’”

Carnaby Street had been the place to shop since the early ’60s, catering mainly to a Mod style – indeed, the Small Faces had accounts at some of the shops – but to those in the know it was becoming too popular as the mid-’60s dawned. “Carnaby Street was the mainstream,” explains Nigel Waymouth. “And we were a reaction away from that. There was a new London look, based in Kensington and Chelsea. There were one or two boutiques, Kiki Byrne and Mary Quant. And then Biba opened up just off High Street Kensington. The look was changing; it was much more flowery, more romantic.”

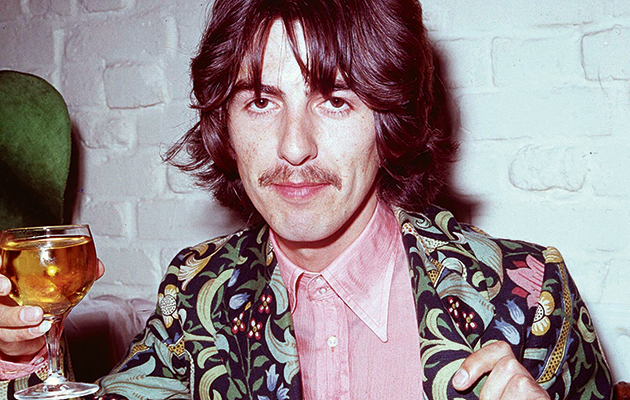

Waymouth and Cohen, then a couple, met tailor John Pearse in 1965, and the trio soon hatched plans to open their own boutique in World’s End on the King’s Road. They also formed their own group, Hapshash And The Coloured Coat, a name Waymouth used for his burgeoning poster company with Michael English. Pearse first made alterations to the clothes that Waymouth and Cohen already had, but soon the three visited stores Liberty and Pontings to buy material – exotic, Asian or floral William Morris designs – with which to create shirts, skirts, dresses, jackets and trousers, all exceedingly tight.

“We were involved in a dandified look that had its roots in the aesthetic movement, people like Oscar Wilde, and fin de siècle sort of swagger stuff,” explains Waymouth. “It starts with the fabric. In Pontings, we found a whole supply of Indian bedspreads which weren’t being used at that time. They were very pretty, and we started to make dresses out of those.”

Waymouth commissioned an Indian bootmakers in Camden Town, Gohil’s, to make patchwork, snakeskin boots in various colours, and friends of the trio went to Afghanistan on the hippy trail and brought back sheepskin coats. “I hated the stench of those coats,” laughs Pearse. “They were just old yaks, I’d imagine.”

The newly opened premises at 488 King’s Road was very different from the stuffy boudoirs of Savile Row. Captain America hung above the door, complete with speech bubble proclaiming the Wildean aphorism “one should either be a work of art or wear a work of art”. The shop window was soon smashed and covered with a board that Waymouth would regularly redecorate; Native American chiefs Low Dog and Kicking Bear were overnight replaced by a giant Jean Harlow, and so on. Even the name was a novelty, referencing both the growing drug counterculture and the rising trend for Victoriana and Edwardiana.

Waymouth decorated the inside of the shop in “New Orleans bordello” style, blowing up risqué postcards for pictures and covering the walls with paper he’d marbled in the basement. At the rear of the shop was a Wurlitzer jukebox stocked with classic rock’n’roll. “I loved going to Granny Takes A Trip,” recalls Marianne Faithfull. “I mean, the clothes were badly made, but very, very nice. There were several places like it on the King’s Road, but Granny’s was one of the coolest places you could go.”

“It got a reputation very quickly,” says Chris Joe Beard, guitarist and songwriter in The Purple Gang, “’cos you got Salvador Dalí going in there, and Eric Clapton, people that put it on the map. Salman Rushdie lived in the flat above.”

One of Granny’s first visible successes could be seen on the back cover of The Beatles’ Revolver, with the group sporting long-collared John Pearse shirts. “After that,” says Pearse, “people would come in and say, ‘Oh, can I have a shirt like Lennon had?’ ‘Well, no you can’t, we’re not making them any more.’ That’s how we were, we never cashed in on anything. We just didn’t care about money.”