Onboard his battlebus, Uncut is granted a conference with the laidback potentate of country music, WILLIE NELSON. On the agenda: Patsy Cline, Johnny Cash, a sanctified guitar, an army of Willie Nelson clones, and the simple business of being America’s best-loved outlaw. Originally published in Unc...

Onboard his battlebus, Uncut is granted a conference with the laidback potentate of country music, WILLIE NELSON. On the agenda: Patsy Cline, Johnny Cash, a sanctified guitar, an army of Willie Nelson clones, and the simple business of being America’s best-loved outlaw. Originally published in Uncut’s July 2010 issue (Take 158). Words: Andrew Mueller

__________________________________

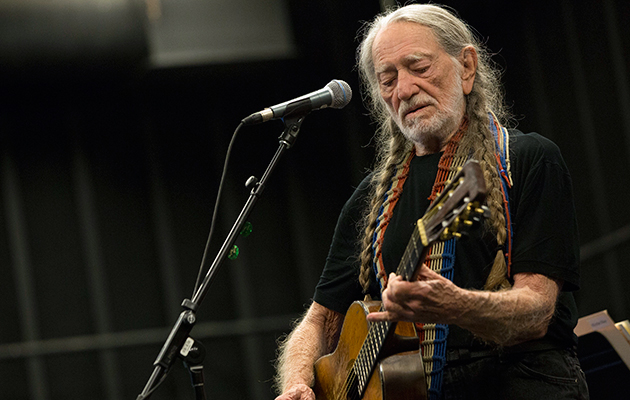

Even amid the gaudy bustle of midtown Manhattan, Willie Nelson’s bus is hard to miss. It’s a bronze leviathan airbrushed with lurid western scenes, parked on West 53rd Street alongside the Ed Sullivan Theater, where Nelson is due to make an appearance on David Letterman’s show later this evening. Nelson, wearing a purplish plaid shirt draped over black T-shirt and jeans, emerges from a room at the back of the bus, and parks himself on the seat at the table opposite the kitchenette. Many are the musicians who complain about life on the road. Nelson, who has lived it longer than most, is not among them (indeed, one of his best-known songs – “On The Road Again” – is a celebration of the touring musician’s lot).

“This bus has done about a million miles in the last five years,” he says, and he does not appear to be exaggerating for comic effect. “It’s just much more fun doing it by bus than any other way – and I’ve done it every other way. Flying is too big a hassle. And this is more like home. I’ve got everything I need here – a bed, a shower, a stove. I very seldom go into the hotel. The rest of the band check in, and I stay here.”

A noticeboard behind him is pinned with photos and assorted touring ephemera. On the table before Nelson are components of a contraption that look suspiciously like they’ve recently been used to smoke dope (Nelson’s enthusiasm for dope is sufficiently legendary to have inspired other country singers: Toby Keith wrote a song called “Weed With Willie” in 2003). Nelson has long been an ardent campaigner for reform of marijuana laws, and cannot be accused of not knowing his subject. He has been busted many times, and several of his band and crew were charged with possession of marijuana and moonshine in North Carolina as recently as January (although Nelson says of himself that “They [the police] mostly leave me alone, now.”) In April, Nelson admitted to Larry King during an interview on CNN that he was stoned (something that King should probably have spotted when Nelson started mumbling about 9/11 conspiracies).

Nelson is, unsurprisingly, an altogether mellow and affable conversationalist. A few days earlier, I’d seen him play in Binghamton, in upstate New York. He laughs delightedly when I mention the proportion of men in the crowd who looked like him – apparently, they’re a regular feature of his shows (“Aw, they’re great,” says Nelson, “did you see some good ones?”). So, it seems, is the pre-show veneration of Nelson’s battered guitar, Trigger. The decrepit acoustic has logged uncountable miles with Nelson, and by the look of it has been dragged behind the tour bus for most of them. When delivered to the stage in anticipation of Nelson’s arrival, it prompted a surge of camera-brandishing worshippers. Are there any special measures taken for the guitar’s safe transport?

“I just keep it with me all the time,” he shrugs. “We had to get a new case, because the old case wore out, but I just keep it back there. I sleep with it.”

Is it insured for some fantastic sum?

“No.”

What’s special about it?

“Well,” he considers. “I’m a big Django Reinhardt fan, and this guitar has a similar sound to Django’s guitar. I think that’s the most important thing. I’ve had other guitars, but that’s the sound I really like.”

It sounded fine in Binghamton, NY, anyway. Nelson himself had appeared in increments. His opening act was his son, Lukas – one of nine children from four marriages (the first three of which were, at the very least, eventful – his first wife beat him with a broom handle, and his second threatened him with a gun when she found out about the woman who would become his third).

Though there were few surprises in Nelson Sr’s setlist, he’d ambled amiably through “Whiskey River”, “Georgia On My Mind”, and “Mama, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Cowboys”, giving every impression that, at the very least, he didn’t object to being up there. People threw gifts onto the stage, mostly baseball caps: he picked them up, squinted at the logos to make sure they didn’t endorse anything he wouldn’t want to be photographed in, wore them briefly, and tossed them back. He solicited applause for the band, especially his sister, Bobbie, on piano, and for his temporary drummer Billy English, stepping in for his brother and Nelson’s old friend Paul English, who had recently suffered a stroke. Inevitably, Nelson dedicates “Me & Paul” to him. A Nelson staple since 1971 album Yesterday’s Wine, it recalls what was, at that point, merely a decade and half’s dissolute friendship. The stories of misadventure the song recalls – about being almost busted in Laredo, refused boarding of an aircraft in Milwaukee, overdoing the hospitality in Buffalo and neglecting to play the show – are all, both Nelson and English have repeatedly insisted, true.