The Velvet Underground man’s knob-twiddling years. You hire John Cale to produce your record; what do you expect? Logically, you might expect the unexpected, because as a musician, Cale has always been an artful butcher, pulling the guts from songs and snapping the sinews; then adding poetry, or discord, disquiet, or wit. You might also wonder which Cale was going to turn up: would it be John Cage or Dylan Thomas? Waldo Jeffers or Sister Ray? Well, this survey of Cale’s production work comes with a quote culled from Cale’s autobiography, in which he defines the role of the man behind the desk. The producer, he suggests, has to be “a catalyst, an ally, a co-conspirator”. Sometimes, that will mean introducing conflict. “I always try to approach it from the point of view, what would a Zen master do in these circumstances? That is not to give the artist a direct answer to all his questions, but to suggest a solution by other means.” Try telling that to the Happy Mondays. Actually, let’s start there. Cale’s stewardship of the Mondays’ Squirrel And G-Man LP is not regarded as a success. It was, Cale says, “a very quick nightmare”, made more nightmarish by his sobriety. “The band complained that I was on a health kick and that all I did was sit around eating tangerines.” In the circumstances, faced with the task of producing Bez’s maracas, eating tangerines may be the way to go. And Cale goes some way towards making the Mondays sound like a proper group. The palindromic rap, “Kuff Dam”, has a decent groove. If Shaun Ryder could sing, it might qualify as funk. It would certainly be less abrasive. Of course, if Shaun Ryder could sing, the Mondays wouldn’t be Happy: their appeal is based on the singer resembling a hod-carrier in the midst of a lost weekend. In fact, many of Cale’s more successful productions feature vocalists operating within the borders of their own peculiarities. Nico, who was Andy Warhol’s idea of a soul singer – which is to say, she sounded like the bored ghost of the embalmed Marlene Dietrich – has her mannerisms housed within an elegant production, with pretty piano framing her diction. True, she sings like a bad actor playing somebody who can’t sing, but it makes a kind of sense. Cale’s production of The Modern Lovers was regarded a failure. He quit before their debut album was complete, after a breakdown of trust with Jonathan Richman, but, really, he did a great job. “Pablo Picasso” chugs like the Velvets, and Richman inhabits a place between pathos and comedy while the guitar makes noises like insects being electrocuted. With Patti Smith – another vocalist in the process of finding her voice – you can detect the moment she stopped being a poet and became a rock singer. It occurs one minute and 43 seconds into “In Excelsis Deo/Gloria”. The Cale mix of The Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog” is more percussive, less neurotic, than the mix which made the original release. It also sounds more like The Velvets, which is a smaller problem now than it would have been in 1969. Cale’s later productions are less emphatic. There are novelties (Cristina’s “Disco Clone”), gnarly rock’n’roll (Harry Toledo & The Rockets’ “Who Is That Saving Me”) and absolute disasters (“Sex Master” by Squeeze). Sadly, there’s no place for Sham 69’s debut, “I Don’t Wanna”, which is a shame, because it would be nice to know whether Cale was that blame for the unfathomable success of Jimmy Pursey’s Hersham yobs during punk’s twilight. There are two stand-outs. The Velvet Underground’s “Venus In Furs” is fabulous theatre, while Eno/Cale’s beautiful “Spinning Away” marries Eno’s dreamy melodies with off-kilter rhythms. That’s the real lesson here. If you want a bit of John Cale, you need the whole John Cale. Anything less is a Zen tangerine. Alastair McKay

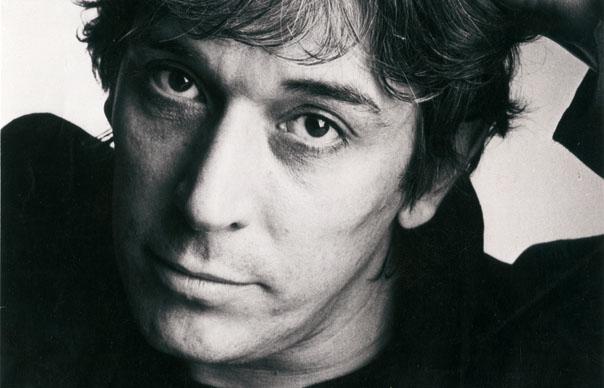

The Velvet Underground man’s knob-twiddling years.

You hire John Cale to produce your record; what do you expect? Logically, you might expect the unexpected, because as a musician, Cale has always been an artful butcher, pulling the guts from songs and snapping the sinews; then adding poetry, or discord, disquiet, or wit.

You might also wonder which Cale was going to turn up: would it be John Cage or Dylan Thomas? Waldo Jeffers or Sister Ray? Well, this survey of Cale’s production work comes with a quote culled from Cale’s autobiography, in which he defines the role of the man behind the desk. The producer, he suggests, has to be “a catalyst, an ally, a co-conspirator”. Sometimes, that will mean introducing conflict. “I always try to approach it from the point of view, what would a Zen master do in these circumstances? That is not to give the artist a direct answer to all his questions, but to suggest a solution by other means.” Try telling that to the Happy Mondays.

Actually, let’s start there. Cale’s stewardship of the Mondays’ Squirrel And G-Man LP is not regarded as a success. It was, Cale says, “a very quick nightmare”, made more nightmarish by his sobriety. “The band complained that I was on a health kick and that all I did was sit around eating tangerines.” In the circumstances, faced with the task of producing Bez’s maracas, eating tangerines may be the way to go. And Cale goes some way towards making the Mondays sound like a proper group. The palindromic rap, “Kuff Dam”, has a decent groove. If Shaun Ryder could sing, it might qualify as funk. It would certainly be less abrasive. Of course, if Shaun Ryder could sing, the Mondays wouldn’t be Happy: their appeal is based on the singer resembling a hod-carrier in the midst of a lost weekend.

In fact, many of Cale’s more successful productions feature vocalists operating within the borders of their own peculiarities. Nico, who was Andy Warhol’s idea of a soul singer – which is to say, she sounded like the bored ghost of the embalmed Marlene Dietrich – has her mannerisms housed within an elegant production, with pretty piano framing her diction. True, she sings like a bad actor playing somebody who can’t sing, but it makes a kind of sense.

Cale’s production of The Modern Lovers was regarded a failure. He quit before their debut album was complete, after a breakdown of trust with Jonathan Richman, but, really, he did a great job. “Pablo Picasso” chugs like the Velvets, and Richman inhabits a place between pathos and comedy while the guitar makes noises like insects being electrocuted. With Patti Smith – another vocalist in the process of finding her voice – you can detect the moment she stopped being a poet and became a rock singer. It occurs one minute and 43 seconds into “In Excelsis Deo/Gloria”. The Cale mix of The Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog” is more percussive, less neurotic, than the mix which made the original release. It also sounds more like The Velvets, which is a smaller problem now than it would have been in 1969.

Cale’s later productions are less emphatic. There are novelties (Cristina’s “Disco Clone”), gnarly rock’n’roll (Harry Toledo & The Rockets’ “Who Is That Saving Me”) and absolute disasters (“Sex Master” by Squeeze). Sadly, there’s no place for Sham 69’s debut, “I Don’t Wanna”, which is a shame, because it would be nice to know whether Cale was that blame for the unfathomable success of Jimmy Pursey’s Hersham yobs during punk’s twilight.

There are two stand-outs. The Velvet Underground’s “Venus In Furs” is fabulous theatre, while Eno/Cale’s beautiful “Spinning Away” marries Eno’s dreamy melodies with off-kilter rhythms. That’s the real lesson here. If you want a bit of John Cale, you need the whole John Cale. Anything less is a Zen tangerine.

Alastair McKay