Noel Scott Engel's journey from easy listening interpreter to fearless songwriter, remastered... To those who knew him in 1966, “loneliness is a cloak you wear” (from “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore”) must have sounded like a line absolutely custom written for Scott Engel. Not only was it a snug fit for his heaven-sent baritone, but it was apposite, too, to his offstage moods of existential angst. Feeling imprisoned by the dreamboat wholesomeness of The Walker Brothers, the 23-year-old Engel was dubbed by NME “the man likely to be more miserable than most in 1967”. Isolation being his best option, he struck out for a solo career that year. Engel still records under his Walker Brothers stage name, although God knows there aren’t many similarities between Bish Bosch and Scott 2. These days his music is all about machetes and raw meat, like the soundtrack to an abattoir. But on his early albums, five of which are collected in this boxset (on CD and vinyl), Walker and his arrangers aimed for something highly sophisticated: a romantic, majestic, orchestral pop inspired by Nelson Riddle’s richly tonal arrangements for Frank Sinatra and by the innovative film scores of Morricone and John Barry. Hoping to establish himself as an important songwriter, Walker put alienation and realistic grit into his poetry, drawing his characters against a harsh metropolitan backdrop. “Such A Small Love” (Scott, 1967) was about a woman being eyed scornfully at a funeral by a friend of the deceased who knew him more intimately than she did. “Montague Terrace (In Blue)”, on the same album, had the echo-laden grandeur of The Walker Brothers’ hits, but its residents lived life on a humbler scale, rattling around their bedsits with only their dreams and the sounds of their neighbours to connect them to the human race. Rather aptly, for Scott’s American release, it was retitled Aloner. Those two songs – and others such as “The Amorous Humphrey Plugg” (Scott 2), “Big Louise” (Scott 3) and “The Seventh Seal” (Scott 4) – are regarded now as classics. It’s strange to think of them being disdained as filler by some fans at the time, who preferred him to drape his voluptuous tonsils around smooth, middle-of-the-road love songs. What unifies Walker’s two distinct personae of 1967-9 – the reclusive intellectual and the cabaret crooner – are his brilliant arrangers (Wally Stott, Reg Guest, Peter Knight) who make sure that we can’t see the join. This is no easy matter when, for example, Walker’s hallucinatory rooftop epic, “Plastic Palace People” (Scott 2), is followed by “Wait Until Dark”, a tune from a popular Audrey Hepburn movie. There should be glaring incongruities, or at least grinding gear-changes, but there are none, even when Walker sings something like “The Big Hurt” (a 1959 Billboard hit) or “Through A Long And Sleepless Night” (from a 1949 musical). His solo career remained for some time a fascinating push-and-pull between High Art and Light Entertainment. One moment he’s singing about a “fire escape in the sky”. The next, the BBC give him his own TV show like Cilla Black. To complicate the picture further, there were the songs of Jacques Brel. Nine of the Belgian’s action-packed tales are spread across Scott, Scott 2 and Scott 3, including “My Death”, “Jackie”, “Amsterdam” and “Next”. Teeming with opium dens and bordellos, cackling whores and bawdy sailors, Brel’s literacy and fearlessness slaked Walker’s craving to produce serious music and effectively changed his life. The influence on his writing was enormous. The barmaid in “The Girls From The Streets”, who “slaps her ass” and “shrieks her gold teeth flash”, could never have existed without Brel. Nor could “fat Marie” and the urine-stained cobblestones in “The Bridge”. Walker’s imagery is wildly overwritten in his coltish desire to out-Brel Brel, and his sentiments are not always plausible, but look at it as he surely did: how liberating to immerse yourself in coarse, potent language when the public have you pegged as the next Tony Bennett. The frosted-up windows of Scott 3 take us into winter. The easy listening ballads and movie themes have gone. Only two songs have a swagger or an exploit they want to boast about: Walker’s “We Came Through” and Brel’s “Funeral Tango”. Otherwise there’s an eerie stillness in the freezing city, where Wally Stott’s violins and harps fall gently and magically like snowflakes. Deeply melancholy, Scott 3 could be seen as a Sinatra-esque rumination on love lost, but it’s also about what happens to forgotten people when memories are all they have left. Writing with a sensitivity beyond his years, Walker introduces us to the lonely Rosemary (“suspended in a weightless wind” with her photograph and clock), the even lonelier Louise (“she’s a haunted house and her windows are broken”) and a pair of elderly tramps (“Two Ragged Soldiers”) who’ve suffered life’s bitterest blows but still take comfort from their friendship. As the Ohio-born Walker applied for British citizenship (which he was granted in 1970), Scott 4 seemed to remind him of the land he’d emigrated from. There are glorious Jimmy Webb panoramas (“The World’s Strongest Man”) and some Bourbon-soaked C&W (“Duchess”, “Rhymes Of Goodbye”). “The Seventh Seal” is the loftiest of starts, summarising the chess game between the knight and Death in Bergman’s film, but despite its solemn conceits, Scott 4 is equally celebrated for its bass-playing by Herbie Flowers, some of the finest and funkiest ever recorded. There’s nothing quite like hearing Flowers cut loose on “Get Behind Me”. If only more people had heard it; instead, Scott 4 saw Walker’s fanbase desert him and the fifth album in this box, ’Til The Band Comes In, is an uneasy compromise between his own material (some of it excellent) and the vanilla MOR standards he felt obliged to sing for a living. The prisoner was once again trapped, a slave to his own voice. Audio note: mastered from original tapes, The Collection 1967-1970 gives Scotts 1–4 a relaxed, room-to-breathe sound. Previous CD editions may seem over-loud in comparison. Differences are less striking between ’Til The Band Comes In and its 1996 BGO reissue. David Cavanagh

Noel Scott Engel’s journey from easy listening interpreter to fearless songwriter, remastered…

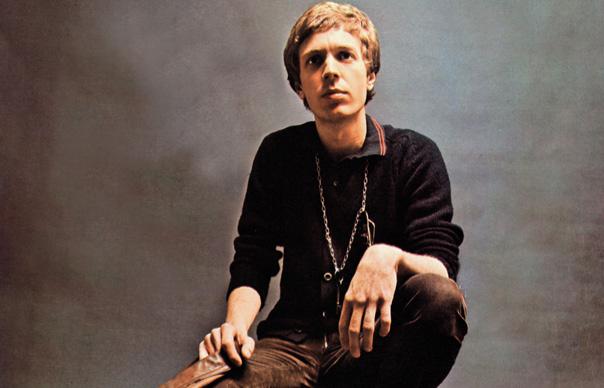

To those who knew him in 1966, “loneliness is a cloak you wear” (from “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore”) must have sounded like a line absolutely custom written for Scott Engel. Not only was it a snug fit for his heaven-sent baritone, but it was apposite, too, to his offstage moods of existential angst. Feeling imprisoned by the dreamboat wholesomeness of The Walker Brothers, the 23-year-old Engel was dubbed by NME “the man likely to be more miserable than most in 1967”. Isolation being his best option, he struck out for a solo career that year.

Engel still records under his Walker Brothers stage name, although God knows there aren’t many similarities between Bish Bosch and Scott 2. These days his music is all about machetes and raw meat, like the soundtrack to an abattoir. But on his early albums, five of which are collected in this boxset (on CD and vinyl), Walker and his arrangers aimed for something highly sophisticated: a romantic, majestic, orchestral pop inspired by Nelson Riddle’s richly tonal arrangements for Frank Sinatra and by the innovative film scores of Morricone and John Barry. Hoping to establish himself as an important songwriter, Walker put alienation and realistic grit into his poetry, drawing his characters against a harsh metropolitan backdrop. “Such A Small Love” (Scott, 1967) was about a woman being eyed scornfully at a funeral by a friend of the deceased who knew him more intimately than she did. “Montague Terrace (In Blue)”, on the same album, had the echo-laden grandeur of The Walker Brothers’ hits, but its residents lived life on a humbler scale, rattling around their bedsits with only their dreams and the sounds of their neighbours to connect them to the human race. Rather aptly, for Scott’s American release, it was retitled Aloner.

Those two songs – and others such as “The Amorous Humphrey Plugg” (Scott 2), “Big Louise” (Scott 3) and “The Seventh Seal” (Scott 4) – are regarded now as classics. It’s strange to think of them being disdained as filler by some fans at the time, who preferred him to drape his voluptuous tonsils around smooth, middle-of-the-road love songs. What unifies Walker’s two distinct personae of 1967-9 – the reclusive intellectual and the cabaret crooner – are his brilliant arrangers (Wally Stott, Reg Guest, Peter Knight) who make sure that we can’t see the join. This is no easy matter when, for example, Walker’s hallucinatory rooftop epic, “Plastic Palace People” (Scott 2), is followed by “Wait Until Dark”, a tune from a popular Audrey Hepburn movie. There should be glaring incongruities, or at least grinding gear-changes, but there are none, even when Walker sings something like “The Big Hurt” (a 1959 Billboard hit) or “Through A Long And Sleepless Night” (from a 1949 musical). His solo career remained for some time a fascinating push-and-pull between High Art and Light Entertainment. One moment he’s singing about a “fire escape in the sky”. The next, the BBC give him his own TV show like Cilla Black.

To complicate the picture further, there were the songs of Jacques Brel. Nine of the Belgian’s action-packed tales are spread across Scott, Scott 2 and Scott 3, including “My Death”, “Jackie”, “Amsterdam” and “Next”. Teeming with opium dens and bordellos, cackling whores and bawdy sailors, Brel’s literacy and fearlessness slaked Walker’s craving to produce serious music and effectively changed his life. The influence on his writing was enormous. The barmaid in “The Girls From The Streets”, who “slaps her ass” and “shrieks her gold teeth flash”, could never have existed without Brel. Nor could “fat Marie” and the urine-stained cobblestones in “The Bridge”. Walker’s imagery is wildly overwritten in his coltish desire to out-Brel Brel, and his sentiments are not always plausible, but look at it as he surely did: how liberating to immerse yourself in coarse, potent language when the public have you pegged as the next Tony Bennett.

The frosted-up windows of Scott 3 take us into winter. The easy listening ballads and movie themes have gone. Only two songs have a swagger or an exploit they want to boast about: Walker’s “We Came Through” and Brel’s “Funeral Tango”. Otherwise there’s an eerie stillness in the freezing city, where Wally Stott’s violins and harps fall gently and magically like snowflakes. Deeply melancholy, Scott 3 could be seen as a Sinatra-esque rumination on love lost, but it’s also about what happens to forgotten people when memories are all they have left. Writing with a sensitivity beyond his years, Walker introduces us to the lonely Rosemary (“suspended in a weightless wind” with her photograph and clock), the even lonelier Louise (“she’s a haunted house and her windows are broken”) and a pair of elderly tramps (“Two Ragged Soldiers”) who’ve suffered life’s bitterest blows but still take comfort from their friendship.

As the Ohio-born Walker applied for British citizenship (which he was granted in 1970), Scott 4 seemed to remind him of the land he’d emigrated from. There are glorious Jimmy Webb panoramas (“The World’s Strongest Man”) and some Bourbon-soaked C&W (“Duchess”, “Rhymes Of Goodbye”). “The Seventh Seal” is the loftiest of starts, summarising the chess game between the knight and Death in Bergman’s film, but despite its solemn conceits, Scott 4 is equally celebrated for its bass-playing by Herbie Flowers, some of the finest and funkiest ever recorded. There’s nothing quite like hearing Flowers cut loose on “Get Behind Me”. If only more people had heard it; instead, Scott 4 saw Walker’s fanbase desert him and the fifth album in this box, ’Til The Band Comes In, is an uneasy compromise between his own material (some of it excellent) and the vanilla MOR standards he felt obliged to sing for a living. The prisoner was once again trapped, a slave to his own voice.

Audio note: mastered from original tapes, The Collection 1967-1970 gives Scotts 1–4 a relaxed, room-to-breathe sound. Previous CD editions may seem over-loud in comparison. Differences are less striking between ’Til The Band Comes In and its 1996 BGO reissue.

David Cavanagh