When Stax Records re-emerged, phoenix like, from the flames of corporate arson in mid-1969, it was with the simultaneous release of 27 albums. The label had lost its entire back catalogue when Warner Brothers took over Atlantic Records, and lost its totemic star, Otis Redding, in a plane crash. Stax...

When Stax Records re-emerged, phoenix like, from the flames of corporate arson in mid-1969, it was with the simultaneous release of 27 albums. The label had lost its entire back catalogue when Warner Brothers took over Atlantic Records, and lost its totemic star, Otis Redding, in a plane crash. Stax looked finished; instead it soared anew.

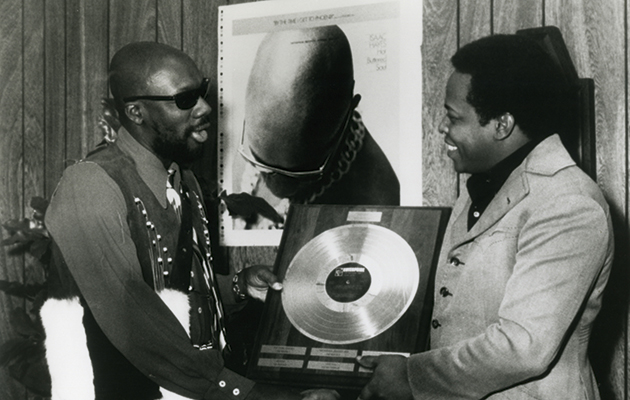

Like the rest of the music industry, the album would prove the future for Stax, with the company kept buoyant by the sprawling, million selling ‘symphonic soul’ outings of Isaac Hayes. Still, even in the early 1970s, the golden age for albums by luminaries like Gaye, Wonder and Mayfield, the African-American market remained tuned principally to the 7” single, where love ballad and dance anthem held sway. Hit singles were no longer the sine qua non of rock music – consider Zeppelin or Floyd – but in soul, the break-out hit remained crucial.

Hence the sheer profusion contained in the two chunky boxes here, some 430 tunes in all, many without any parent album. It’s a more diverse collection than the familiar finger-snapping Stax logo might suggest (in fact, many sides were issued on the subsidiaries of Volt, Enterprise, Respect and We Produce). There is crisp southern funk and deep soul aplenty from both Stax’s star names – Johnnie Taylor, Rufus Thomas, The Staple Singers, The Emotions, Eddie Floyd – and from few-hit wonders like Veda Brown, Jean Knight and Shirley Brown, but there is also blues, ‘northern’ stompers, novelty offerings, Christmas records (including The Emotions’ ”Black Christmas”) film themes (Melvin Van Peebles” “Sweetback Theme”), country covers, and the blue-eyed soul of Delaney and Bonnie.

Such diversity, more apparent on Volume Two, reflected the ambitions of Stax’s new driving force, Al Bell, elevated from head of promotions to Vice President by Stax founder Jim Stewart. Bell saw Stax as an emblem of black pride and empowerment, but he also harboured a vision of Stax as “a total record company” unrestricted by genre. The label’s lifeblood had always been the productions of its McLemore studio, cut with the house band of Booker T and the MGs and the horns of the Markeys, and drawing principally on local talent. No longer. Bell signed acts from all points of the compass, leased ready-made productions and increasingly sent Stax’s acts to record at Alabama’s Muscle Shoals, a studio that had lent its Midas touch to Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett before hosting the likes of the Rolling Stones and Paul Simon.

Bell’s policy was not without success. The Staple Singers, one of the touchstones of the new Stax, sired masterpieces like “I’ll Take You There” and “Respect Yourself” at Muscle Shoals, and among the cross-over hits here are buy-ins like Frederick Knight’s wistful “I’ve Been Lonely So Long”, but the family atmosphere and identity of Stax were broken, to the point where guitarist Steve Cropper, a lynchpin as writer, arranger and player, left in disillusionment.

Still, great singles and contenders for the R&B Charts continued to roll out. Here you’ll find blues classics like Albert King’s “Crosscut Caw” and Little Milton’s “Rainy Day” (alongside John Lee Hooker’s less celebrated “Grinder Man”), intricate vocal harmony pieces like The Dramatics “In The Rain”, complete with elaborate aquatic effects, tough dancers like Veda Brown’s “Short Stopping” and tearful slowies like Mel and Tim’s gospel-soaked “Starting All Over Again” (modelled on Johnny Nash’s “I can See Clearly Now”).

Infidelity and double-dealing are a constant theme, the narrative of Shirley Brown’s “Woman To Woman”, the Soul Children’s “I’ll Be The Other Woman”, Johnnie Taylor’s “Who’s Making Love” (the first big hit of the post-Atlantic era), and William Bell’s overlooked “Gettin’ What You Want (Losin’ What You Have)”. Though soaked in the church traditions of the south, the influence of Ike Hayes’ rap-heavy bedroom crooning is often evident – not least on “Tribute to A Black Woman”, written by Ike and sung by sister (?) Bernice – while Hayes’ own work is arguably more digestible in the edited down single versions of “By The Time I Get To Phoenix”, “Walk On By” et al.

The call of the dancefloor is never far off. The irrepressible Rufus Thomas saw to that with “Funky Chicken” and “Funky Penguin”, while “Singing About Love” by the obscure Jeanne and The Darlings is the kind of belter favoured by Northern Soul aficionados (though the group came from Arkansas). Other curios include Detroit’s Black Nasty, a rock-soul amalgam partial to squealing guitars, and an impromptu grouping of Cropper, Albert King and The Staples for John Lee Hooker’s “Tupelo”.

Such in-studio inventions became increasingly uncommon once Cropper split; there would be no more MGs gems like “Soul Limbo” and “Time Is Tight”. You can feel the energy draining from McLemore Avenue on Volume 3, which is notably lighter on hits despite the increased presence of Stax’s major acts – William Bell, Emotions, Dramatics, Staples et al. The company, plagued by dubious fiscal dealings, wound up in 1975 with a whimper; the end of an era not just for Stax but for soul music, which would soon be eclipsed by disco.