Five-CD boxset from punk years shows the Stranglers were the outsider’s outsiders... From the start, The Stranglers never quite fitted in. They were punk enough to get banned from venues around Britain during the Sex Pistols scare, and their early records - notably “Something Better Change” and “No More Heroes” – were propelled by the energy and anger of the period. They scowled. They wore leather. They were, on occasion, violent. But listen, now, to their first two albums, Rattus Norvegicus and No More Heroes, and you hear a fierce pub rock group, playing fast and loose with their influences. The Doors are there, obviously. The presence of Dave Greenfield on organ, and, later, Moogs, offer a link to prog rock. The vocal hiccups on “Straighten Out” are an echo of Buddy Holly. “Nice N’Sleazy” is almost a reggae song, sung like a robot prophesy. “Peasant in the Big Shitty” is – though this may not be immediately apparent - influenced by Captain Beefheart, who also provided the riff for “Down In The Sewer”. And Don Van Vliet’s impersonation of Howlin’ Wolf was the inspiration for the vocal style of Hugh Cornwell and Jean-Jacques Burnel, even if their interpretation of the bluesman’s growl was inflected with more than a dash of White Van Man. So there was sound and fury, and it felt like punk rock. But it would probably have happened anyway, even if the Sex Pistols hadn’t. In truth, punk as it is now understood was a shapeless, ill-defined thing. It was an energy. The Stranglers were fortunate enough to have an album and a half worth of songs ready to go when the nascent movement hit the mainstream, and though they radiated a sense of danger and malevolence, their songs were rarely political. True, there was “I Feel Like A Wog”, an unthinkable sentiment now, though its intention was, the group argued, to identify with the downtrodden. Their apparent sexism was also out-of-tune with the ideological assumptions of the day, though that may have been the point. Their first hit, “Peaches”, was a voyeuristic prowl along a beach, with lyrics which included a rather confusing reference to a clitoris. It was educational in a way. Clitorises weren’t as prevalent in popular culture in 1977 as they are now. But if it was discomfiting, it was also honest about male (hetero)sexuality. This set collects the six albums made for United Artists, adding a disc of oddities, including radio edits of singles, and (largely unnecessary 12” remixes). The rarities aren’t all that edifying, though the thin humour of an early novelty number, “Tits” (live at the Hope and Anchor) does illuminate a persistent feeling that the real roots of the Stranglers were in musical theatre, possibly burlesque. (The song itself is rotten). And the tunes originally released as Celia and the Mutations (“Mony Mony” and “Mean To Me”) – show how they were capable of turning their hand to pop, albeit with marginal commercial success. Their biggest hit, “Golden Brown” came towards the end of their tenure at UA, just as the label was giving up on them, and on punk. True, the record company had endured 1981’s The Gospel According To The Meninblack, a heroin-induced space opera laden with squeaky voices and Clangers-style sound effects. (Or, if you are on the right medication, a visionary precursor of techno). But if it did nothing else, that lengthy experiment with Class “A” drugs produced the lovely “Golden Brown”, the highlight of 1981’s La Folie, and perhaps the prettiest hymn to stupefaction not written by Lou Reed. Musically, it showed how far the Stranglers had travelled. The riff is played on a harpsichord, and lopes along in bleary waltz-time. The anger and venom of punk is entirely absent. Cornwell sings prettily. But perhaps there’s a note of exhaustion in his delivery too. For, although the title track of La Folie has a kind of early 1980s’ majesty, and bit of Euro-weirdness, courtesy of Burnel’s Serge Gainsbourg-style vocal, the energy is gone. True, the single “Strange Little Girl” (a rejected song, revived in the hope of repeating the success of “Golden Brown”) had a delicate melody, but 1980s’ pop was about frivolity and light, not ennui. The Stranglers, whose dark energy had soundtracked the Winter of Discontent, were outsiders again. Alastair McKay

Five-CD boxset from punk years shows the Stranglers were the outsider’s outsiders…

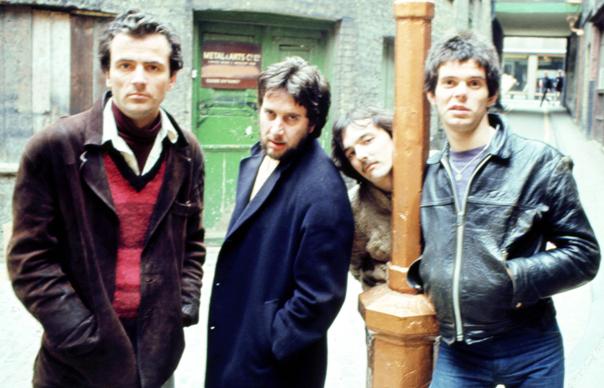

From the start, The Stranglers never quite fitted in. They were punk enough to get banned from venues around Britain during the Sex Pistols scare, and their early records – notably “Something Better Change” and “No More Heroes” – were propelled by the energy and anger of the period. They scowled. They wore leather. They were, on occasion, violent.

But listen, now, to their first two albums, Rattus Norvegicus and No More Heroes, and you hear a fierce pub rock group, playing fast and loose with their influences. The Doors are there, obviously. The presence of Dave Greenfield on organ, and, later, Moogs, offer a link to prog rock. The vocal hiccups on “Straighten Out” are an echo of Buddy Holly. “Nice N’Sleazy” is almost a reggae song, sung like a robot prophesy. “Peasant in the Big Shitty” is – though this may not be immediately apparent – influenced by Captain Beefheart, who also provided the riff for “Down In The Sewer”. And Don Van Vliet’s impersonation of Howlin’ Wolf was the inspiration for the vocal style of Hugh Cornwell and Jean-Jacques Burnel, even if their interpretation of the bluesman’s growl was inflected with more than a dash of White Van Man. So there was sound and fury, and it felt like punk rock. But it would probably have happened anyway, even if the Sex Pistols hadn’t.

In truth, punk as it is now understood was a shapeless, ill-defined thing. It was an energy. The Stranglers were fortunate enough to have an album and a half worth of songs ready to go when the nascent movement hit the mainstream, and though they radiated a sense of danger and malevolence, their songs were rarely political. True, there was “I Feel Like A Wog”, an unthinkable sentiment now, though its intention was, the group argued, to identify with the downtrodden. Their apparent sexism was also out-of-tune with the ideological assumptions of the day, though that may have been the point. Their first hit, “Peaches”, was a voyeuristic prowl along a beach, with lyrics which included a rather confusing reference to a clitoris. It was educational in a way. Clitorises weren’t as prevalent in popular culture in 1977 as they are now. But if it was discomfiting, it was also honest about male (hetero)sexuality.

This set collects the six albums made for United Artists, adding a disc of oddities, including radio edits of singles, and (largely unnecessary 12” remixes). The rarities aren’t all that edifying, though the thin humour of an early novelty number, “Tits” (live at the Hope and Anchor) does illuminate a persistent feeling that the real roots of the Stranglers were in musical theatre, possibly burlesque. (The song itself is rotten). And the tunes originally released as Celia and the Mutations (“Mony Mony” and “Mean To Me”) – show how they were capable of turning their hand to pop, albeit with marginal commercial success.

Their biggest hit, “Golden Brown” came towards the end of their tenure at UA, just as the label was giving up on them, and on punk. True, the record company had endured 1981’s The Gospel According To The Meninblack, a heroin-induced space opera laden with squeaky voices and Clangers-style sound effects. (Or, if you are on the right medication, a visionary precursor of techno).

But if it did nothing else, that lengthy experiment with Class “A” drugs produced the lovely “Golden Brown”, the highlight of 1981’s La Folie, and perhaps the prettiest hymn to stupefaction not written by Lou Reed. Musically, it showed how far the Stranglers had travelled. The riff is played on a harpsichord, and lopes along in bleary waltz-time. The anger and venom of punk is entirely absent. Cornwell sings prettily.

But perhaps there’s a note of exhaustion in his delivery too. For, although the title track of La Folie has a kind of early 1980s’ majesty, and bit of Euro-weirdness, courtesy of Burnel’s Serge Gainsbourg-style vocal, the energy is gone. True, the single “Strange Little Girl” (a rejected song, revived in the hope of repeating the success of “Golden Brown”) had a delicate melody, but 1980s’ pop was about frivolity and light, not ennui. The Stranglers, whose dark energy had soundtracked the Winter of Discontent, were outsiders again.

Alastair McKay