Early 1973. The Melody Maker’s Michael Watts is on a plane from Durango to Mexico City, with at least some of the cast and crew of Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid. Across the aisle from Watts is the amiable and forthcoming star of the movie, Kris Kristofferson, generous enough to be sharing his bottle of Jameson’s with the writer.

Just behind Kristofferson, with a straw hat pulled right down over his face, sits another member of the cast; one who shares a trailer with Kristofferson on set, but can let days go by without even speaking to his supposed friend. A newcomer to acting, whose pathological guardedness leads the film’s publicist to describe him to Watts as, “just rude”. A man renamed, for the purposes of Sam Peckinpah’s movie, as Alias.

“This guy can do anything,” says Kristofferson, marvelling. “In the script he has to throw a knife. It’s real difficult. After 10 minutes or so he could do it perfect. He does things you never thought was in him. He can play Spanish-style, bossa nova, flamenco…one night he was playing flamenco and his old lady, Sara, had never known him do it at all before.”

Watts, possibly emboldened by the liquor, confides in Kristofferson that he is scared to speak to this glowering enigma. “Shit, man,” Kristofferson roars. “You’re scared. I’m scared, and I’m making a picture with him!”

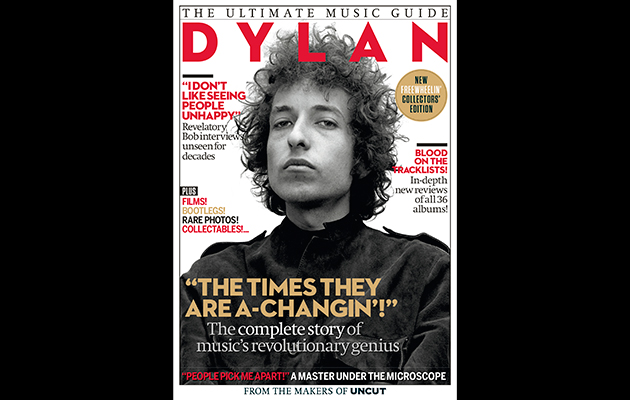

Fear. Mystery. Confusion. Awe. The magnetic strangeness of Bob Dylan has now dominated our world for over half a century, casting a long shadow over most everyone who has followed in his wake. The prospect of compiling an Ultimate Music Guide dedicated to the great man was itself rather daunting, which may explain why it’s taken us so long to put together this very special issue (It’s in UK shops on Thursday, but you can order a Dylan Ultimate Music Guide from our online store right now).

Anyhow, we pursue rock’s most capricious and elusive genius through the back pages of NME and Melody Maker, revisiting precious time spent with Dylan over the years: from a relative innocent in a Mayfair hotel room, complaining about how, already, “people pick me apart”; to a verbose prophet of Armageddon revealing, with deadly intent, “Satan’s working everywhere!”

To complement these archive reports, we’ve also written in-depth new pieces on all 36 of Dylan’s storied albums, from 1962’s “Bob Dylan” to this year’s “Shadows In The Night”; 36 valiant, insightful attempts to unpick a lifetime of unparalleled creativity, in which the rich history, sounds and stories of America have been transformed, again and again, into something radical and new. In which Dylan has revolutionised our culture, several times, more or less single-handedly.

“‘Tombstone Blues’ proved Dylan had not exactly abandoned protest music, more broadened the scope of his protest to accurately reflect the disconcerting hyper-reality of modern western culture,” writes Andy Gill, in his exemplary essay on “Highway 61 Revisited”. “It was a transformation which would change the way that both artists and audiences alike regarded their relationship with the world. No mean feat for rock’n’roll.”