After a slightly tricky month recovering from a bike accident, I went out to a gig for the first time in a while last night, to see Joanna Newsom. We have an issue to finish, and Laura is due to file a proper review of the show any second, but it's hard for me to witness such a performance without m...

After a slightly tricky month recovering from a bike accident, I went out to a gig for the first time in a while last night, to see Joanna Newsom. We have an issue to finish, and Laura is due to file a proper review of the show any second, but it’s hard for me to witness such a performance without making a few notes about it.

First up, I’ve seen Newsom play a good few times, solo and accompanied, and I think this might have been the best yet. I guess that might in some part be due to exponential growth; she has, after all, four albums to draw from now, and in fact a four-album run of such richness that I’m hard-pressed to think of a latterday equivalent. While “Divers” is in some ways her most accessible album, it still reveals itself in a gradual and insidious way, growing in potency and emotional heft dozens of listens down the line. Last night, “A Pin Light Bent”, “Time As A Symptom”, the baroque soul of “Goose Eggs” and the title track were all stunning, not out of place alongside canonical business like “Cosmia”, “Bridges And Balloons”, “Peach Plum Pear” and the straight-up best version I’ve ever heard of what I think remains her best song, “Emily”: “Threw the window wide and cried Amen! Amen! Amen!”

The incredible depths of “Have One On Me” were pointed up, too, with startling versions of two songs that I don’t usually pay so much attention to, “Baby Birch” and “Soft As Chalk”, the latter now sounding like her own “Heroes And Villains”, an elaborate frontier fantasia. A good part of this is due, of course, to the immense craft and meaning that goes into her songs, and into a performance that, for those of us who can’t play any instrument, let alone a harp – is also one of virtually unimaginable finesse and stamina.

But I also think one of the strengths this time out is how her band have now worked out a way of filling out these maze-like songs in a way that remains tricksy and imaginative, but in a more discreet and empathetic way than they did circa “Have One On Me”. Ryan Francesconi and his arcane string arsenal remains at the heart of affairs, but there’s a lot more supplementary keyboards from the multi-instrumentalists, Mirabai Peart adding harmonies as well as fiddle, and a drummer – Pete Newsom – who’s less ostentatious in his quirks than his admittedly brilliant and improvisatory predecessor, Neal Morgan.

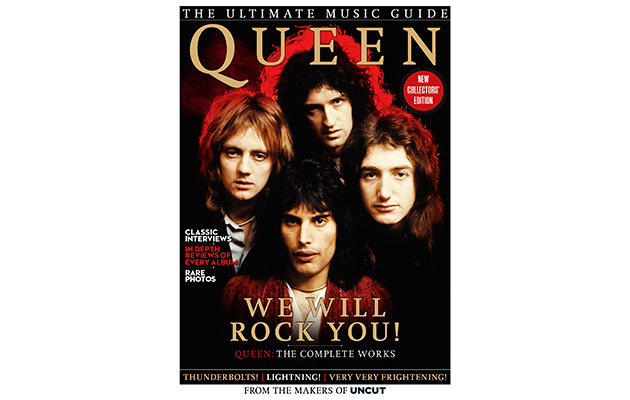

Judging by my Twitter feed, plenty of you were there, too; I’d be interested to know what you all thought. But in the meantime, we have a new Ultimate Music Guide to plug, this time dedicated to Queen (It’s on sale on Thursday, but you can order the Queen Ultimate Music Guide now from our online shop). I was away when this one went to bed, and am very grateful for John Robinson’s help in getting it finished, so it seems only right that he should be the one to introduce the issue.

Here’s John…

In the early winter of 1974, something changed with Queen. With the October release of “Killer Queen”, the group’s unique character – a versatile and musicianly rock; a love of clever lyrics in the tradition of Noel Coward – became less of a problem, more an opportunity. Somewhere between the denim jackets of the rock heartland and the stack-heeled boots of Top Of The Pops, Queen found their audience.

It’s a moment articulated precisely by David Cavanagh in his review of 1974’s Sheer Heart Attack, just one of the fine pieces of writing you’ll find in this authoritative collectors’ edition. Here you’ll find every Queen album re-appraised, and displayed alongside contemporary articles from across the band’s spectacular career.

Had the world changed in 1974, or had Queen changed? Never a critics’ band, Queen’s relationship with the press remained amusingly rebarbative in good times and in bad, encounters relayed for your enjoyment here in full, outrageous colour. If the rock press treated Queen with suspicion (and barely-concealed homophobia), even in early career, Freddie Mercury had developed a persona to withstand them, and any of his own vulnerabilities. At one point an interviewer wonders if the singer is vain.

“My dear I’m the vainest creature going,” he replies with some élan, still some months from his commercial breakthrough. “But so are all pop stars…”

If it was designed to repel the press, this same persona, over the 17 years until Mercury’s death in 1991 (and beyond that event, via their million-selling compilations, live albums and the posthumous studio album Made In Heaven) helped Queen enjoy an enormously close relationship with its public.

As the pieces in our Ultimate Music Guide reveal, this was far from accidental. Into a rockist landscape, Queen injected a sense of fun, and willingness to please a crowd. Their operatic hit “Bo Rhap” (as “Bohemian Rhapsody” quickly became known) could not be played fully, authentically, live. Queen embraced the fact. They left the stage leaving backing tapes to deal with the song’s six-part harmonies, and returned in new costumes to rock out at the close.

Queen’s was a music that balanced gesture and authenticity, pop and rock, business and pleasure. If there is a struggle in their tale, it is a non-traditional one. Having initially resisted their commercial potential, Queen gave in to their ability to please crowds – and gave the people what they wanted, a policy which they developed to a fine art. Their unrivalled Greatest Hits album was unrivalled for a reason – the tracklisting even changing from region to region, to provide the audience with the optimum experience.

It’s a policy that continues to this day. Once Queen get you, they will not let you go.