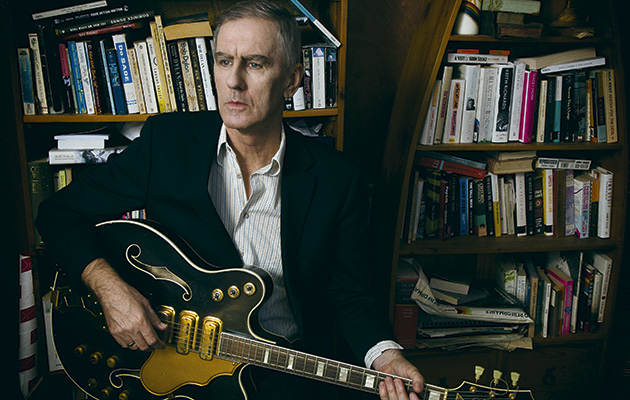

The London Review Of Books café, in Bloomsbury, seems an apt place to meet Robert Forster. As we will discover, he meticulously recreated a photograph of James Joyce for the cover of his debut solo album. “Joyce and Beckett,” he says, “were some of my style heroes.” Today, Forster could pl...

The London Review Of Books café, in Bloomsbury, seems an apt place to meet Robert Forster. As we will discover, he meticulously recreated a photograph of James Joyce for the cover of his debut solo album. “Joyce and Beckett,” he says, “were some of my style heroes.”

Today, Forster could plausibly pass as an academic on a study trip from the Antipodes (he is indeed currently grappling with something akin to a memoir), or perhaps a senior diplomat, taking in a little culture at the British Museum between appointments in Whitehall. The sober and precise demeanour, however, cloaks a different kind of man of letters: a quixotic singer-songwriter, whose work with Grant McLennan made The Go-Betweens one of the finest and most romantic bands of their time; and whose solo albums, often neglected, are every bit as rewarding. Like so many idiosyncratic talents before him, especially those who came of age in the 1980s, Forster’s tale pits a nuanced vision against wave after wave of sonic compromises: “It was a push and pull,” he recalls, “between us owning our music, and having it tampered with.”

THE GO-BETWEENS

BEFORE HOLLYWOOD

ROUGH TRADE 1983

After a clutch of cult singles and a good, if rather awkward, debut album (1981’s Send Me A Lullaby), Robert Forster, Grant McLennan and drummer Lindy Morrison fetch up in London and sign to Rough Trade. Soon, they are dispatched to Eastbourne, where Forster and McLennan’s timeless songcraft is uncovered by their first proper producer.

We had to make a classic. Our first album was not a classic album, and you don’t know how many chances you’re going to get. We’d never really worked with a producer, and we talked with Geoff Travis about our fantasy candidates, people like Lindsey Buckingham and Robbie Robertson. But John Brand walked into our rehearsal room, taped us, then walked back the next day with the songs written out and with arrangement ideas; no one had ever done that with our music.

John had been working for Virgin with groups like Magazine and XTC, and realised everything we were doing was in fours and eights, it was all classic. That’s what Grant and I had been brought up on: Neil Diamond writing for the Monkees, the first Blondie Album, David Bowie, Creedence. We knew how songs were constructed.

And so Grant and I had the songs, most of them written in London and then recorded in Eastbourne. The studio was called ICC, a very good Christian studio that no longer exists; 24-track, two-inch tape. I don’t know how John found it. The album he did before Before Hollywood was High Land, Hard Rain, Aztec Camera walked out the door and we walked in, and John made two classics.

It was the album we always thought we could make, and a very big sonic jump from Send Me A Lullaby. I don’t know if we made a jump like that in the rest of our career, except maybe to 16 Lovers Lane.

THE GO-BETWEENS

SPRING HILL FAIR

SIRE 1984

Deep in Provence, the Go-Betweens – now augmented by Robert Vickers on bass – are encouraged to try on the accoutrements of ‘80s pop, with mixed results. One gleaming and drum machine-driven single, “Bachelor Kisses”, “spooked people”…

Geoff Travis couldn’t finance our next album with Rough Trade, so he took us to Sire. Seymour Stein trusted Geoff’s ears and was very hands-off: he’d just signed Madonna, so I think his attention was somewhere else. We were down in a studio in Provence, isolated, and it was hard to get co-ordinates on what we were doing. Miraval was quite a cathedral-like studio, luxurious, and we thought it was going to be like Before Hollywood again. But John Brand came in with a different attitude, and we were trapped there in the south of France, going through this thing about drum machines. Y’know, we’re in the ‘80s, there’s a highly synthetic approach to pop, and so suddenly all these mechanisms started. For us, Spring Hill Fair didn’t have the swing and the natural feeling of Before Hollywood

Another thing is Grant’s song selection. There are songs like “River Of Money”, a five-minute feedback sprawl, instead of two gorgeous pop songs we’d demoed called “Attraction” and “Emperor’s Courtesan” [both included on this year’s G Stands For Go-Betweens boxset]. Grant was always perceived as the pop kid in the band, but he didn’t pick the pop songs. At times I would try and sway him on material, because he had a lot more than me: I would have four or five songs for each album and he would have 15 or 20. But he chose avant-garde weirdness over pop, and I admired him for it – it made the record very varied.

There are some great songs on Spring Hill Fair, and things I like about the album a great deal, but it starts a problem that runs all the way through our career, especially in the ‘80s; wrestling for control of our music.

THE GO-BETWEENS

LIBERTY BELLE AND THE BLACK DIAMOND EXPRESS

BEGGARS BANQUET 1986

Yet another label change brings the band to the relative security of Beggars Banquet. Rebelling against the glossy expediencies of Spring Hill Fair, the quartet hunker down in Farringdon, London, with engineer Richard Preston, and produce what might conceivably be their masterpiece.

Liberty Belle was us taking control again. Every record a band makes is, in essence, a response to the one before – and so it was with us. We came out of Spring Hill Fair with a list of things that, next time, we weren’t going to do. We were going to produce it or be co-producers. We weren’t going to have drum machines. We were going to have natural instrumentation. There was a feeling that maybe we were only going to be given one more chance, so we were going to go down in flames for what we believed in

We were an amazing band but we were going nowhere, and Grant and I were pissed off, so the career of the band became our subject matter. Our hard luck stories and cynicism were exacerbated by the fact that Liberty Belle was our fourth album on our fourth record label. It was a disaster for our career: we weren’t like U2, Echo And The Bunnymen, The Smiths, REM. They had a system and there was organic growth. We were being dragged back to the start every time.

It’s also the first album that reflects the role of London. It was the first time we let the city we lived in come into what we do, especially on “Twin Layers Of Lightning” and “The Wrong Road”. It’s very much us as a group, ‘the four Australians’. Lindy, Robert Vickers, Grant and I had been going for a number of years, so we could really do the songs justice. People could put mics around us and we could play the songs.

The songs were easily the best batch I’d written in that phase. I rediscovered melody, linked to the way I wrote in the late ‘70s. On those first singles, I used to be the singles writer, and it was almost as if I’d forgotten that. But then, in the summer of 85, I wanted a pop sensibility again in what I did, And because the songs were a little bit slower, I had more room for lyrics. I could say things instead of that post-punk thing where it’s a yelp and a scream and a few words here and there. I could blurt out whole lines and get verses going. Lyrically, it was a lot richer.

A big influence for me at the time was Prince, who I just adored. Everyone who was mainstream at that time was so po-faced. Even someone like Springsteen was very serious, whereas Prince was impish, winking, extravagant – everything I wanted a pop star to be. He made me realise that you can be in the mainstream and play with form.

THE GO-BETWEENS

16 LOVERS LANE

BEGGARS BANQUET 1988

The see-sawing continues, with Tallulah (1987) again flirting with commercial trickery, before a return to Australia brings a sunny, mature climax to the Go-Betweens’ first phase.

We’d just moved back to Australia after five and a half years in London, having had enough of the darkness and the cold and the poverty. We’d spent about a year on the road with Tallulah, becoming more successful, and we thought, ‘Why can’t we do that from Sydney?’ Amanda [Brown, violin] was from Sydney, and Lindy had a brother there, and so the album arrived like a Sydney summer – it’s crystal, it’s sunshine.

16 Lovers Lane was an album where Grant’s and my songwriting came together. It’s a very united ten songs. Although we were completely enamoured with love songs, we’d never used the word ‘love’ in a song title, but then we sat down and Grant played “Love Goes On” for me and I played “Love Is A Sign” for him. It was fate. And in terms of our romantic lives at that time, you could really see them in the lyrics: Grant’s songs were written in the first throes of love for Amanda; Lindy and I had broken up just after Liberty Belle, and my romantic life was chopping and changing. They were love songs from two different views: someone who’s in love and someone who’s wandering around.

The last two albums [producer] Mark Wallis had worked on were The Joshua Tree and Naked by Talking Heads, he was about the hottest guy in the world. We sent him a demo from Australia and the first thing he said to me and Grant was, ‘That’s the best demo I’ve ever heard in my life.’ No-one can record acoustic guitars like Mark. It sounds like it’s coming from the mountain and it’s 1970 and you’re playing an acoustic guitar that David Crosby’s just handed to you.

ROBERT FORSTER

DANGER IN THE PAST

BEGGARS BANQUET 1990

After 16 Lovers Lane, and enduringly moderate levels of success, Forster and McLennan choose to go their separate ways. The former settles in Germany, and recruits a clutch of Bad Seeds for a twanging, wild mercury session in Berlin’s storied Hansa studios.

A personal favourite. I’d visited Hansa when we were on tour in 1987 in Berlin, and I said, ‘I want to record here, one day I’m going to come back.’. But then the band broke up and I was living in Germany. I wanted Mick Harvey to produce my album, and we recorded it in a way that I’d wanted the Go-Betweens to record but had been, to an extent, thwarted – in a big studio, live, trusting the songs and the glorious sound. In Hansa you don’t have to double track an electric guitar, everything’s so big. It’s a sound that goes back to Buddy Holly’s records or to Highway 61 – there are no overdubs on those records. We did it in 12 days, recorded and mixed, with Hugo Race, Thomas Wydler and Mick – a very tight crew – and it was a beautiful experience.

When you write a song like “Danger In The Past”, that changes your perception of who you are as a songwriter, it’s fantastic, especially after you get past the age of 30. It was like a folk song, and none of my songs on any Go-Betweens record were like that or had six verses. It had a classic folk chord sequence that Neil Young could’ve written, that Gordon Lightfoot could’ve written

I came across a photo of James Joyce in a library in Ravensburg University, where my wife was studying. Joyce looks a bit like my grandfather, so I decided to replicate the photo for the cover and make no mention of it; just send it out in the world and see what people made of it.

ROBERT FORSTER

WARM NIGHTS

BEGGARS BANQUET 1996

Back in Australia, Forster completes one more album (Calling From A Country Phone, 1993) and a covers set (I Had A New York Girlfriend, 1995). What can break his writer’s block? A balmy Brisbane suburb? Roberta Flack? Old Postcard chum Edwyn Collins?

I’d moved back to Brisbane to record Calling From A Country Phone, but I hadn’t written any songs for two and a half years. I thought my songwriting career was over – I recorded I Had A New York Girlfriend because I had to try and do something. But suddenly I started to listen to an album by Roberta Flack called First Take, which is amazing. It’s very sparse, and I started to wonder about songs with more groove, about getting away from more narrative pop songs. It was about sweaty Brisbane nights, banana trees in the backyard, animals walking around at night, fruitbats flying in the air. I was looking at Brisbane with new eyes in this new suburb, and I was listening to this music that had more space, more rhythm. Don’t try and write complicated pop songs with lots of lyrics, stay on one chord like “Some Kinda Love” by the Velvets, or “What Goes On”; just groove.

I wrote all the songs in about eight months, quicker than I had written since the late ‘70s, and I brought all of those songs to the UK. Edwyn Collins was building his studio and would have to go off to South Korea to be on TV. He would have to go off to Glasgow and see Rod Stewart covering “A Girl Like You”. The greatest regret of my solo career is that I didn’t bring my band over and get that Brisbane thing totally going on the record. But I never made a bad record in London. I love the rock’n’roll history of this town. There’s something here in my imagination that I can plug into.

THE GO-BETWEENS

THE FRIENDS OF RACHEL WORTH

CIRCUS/JETSET 2000

The Go-Betweens – or at least Grant and Robert – reconvene, in the hip, DIY environs of Portland. An uncommonly fruitful reunion begins in earnest.

I moved back to Germany with my wife in early 1997. Beggars had dropped me – I had no record label. I was 40, and ready to absolve my ego and my career, and admit children into my life. We wanted to have a very protective, nest-like environment for our children to grow up in, and so that’s what I was thinking of while writing songs. But I’m out of the game – that’s how I was feeling.

Then Beggars Banquet wanted to put out a single CD Best Of [Bellavista Terrace, 1999]. Grant and I were friends all the time, so we decided to play clubs under our own names, not as The Go-Betweens. Very soon into the tour, Grant said ‘let’s restart the band’. I didn’t see it coming.

Grant and I were on the road and looking for a place to record. We were down to the last two or three dates and had no leads. The first show was in Portland and I got interviewed by Larry Crane, who had a studio. One of my favourite bands in the late ‘90s was Sleater-Kinney, and the next night we played in San Francisco and they were at the gig. I announced from the stage that we were going to restart the Go-Betweens and record an album, and Janet [Weiss] from Sleater-Kinney walked in after the show and said ‘I’ll be your drummer if you’re looking for one.’

Joanna Bolme.[The Jicks] picked us up from the airport and she had this wallet of CDs in her van. I’d never met her, but it was like a sign. I was flipping through these records and I knew every one of them. I thought, we’ve landed into a scene here that totally understands us, that Grant and I felt great affinity with, but that we hadn’t known existed.

THE GO-BETWEENS

OCEANS APART

LO-MAX 2005

If Rachel Worth privileged Forster’s wired garage rock aesthetic, the final Go-Betweens album highlights McLennan’s more orthodox, polished take on pop. 16 Lovers Lane producer Mark Wallis helms what becomes the most critically acclaimed album of the band’s career.

We could have made our comeback with Mark, but we were wilful. We followed a line that was unpredictable, but now we were ready for Mark and we were ready for London It was made in very chaste conditions. He was working in his little studio in a very rough part of London, down the hill from Crystal Palace. Rough, rough. Our hotel was up on the hill at Crystal Palace and what the record is now, the way I see it, is a sort of dark, foggy, London Gothic. We were in this gothic mansion and we’d walk through the forest, down to where there was urban warfare going on, to record the album. It was like I’d walked back into the 19th Century.

We were working with Glenn [Thompson, drums] and Adele [Pickvance, bass], a very tight band, we got on really well. From those last three albums [also including 2003’s Bright Yellow Bright Orange], these were Grant’s best group of songs. He really hit his stride on that album. Mark suited Grant, and Mark loved Grant’s guitar playing, because Grant was a riff merchant.

Grant wrote a great group of songs after that, and I think the next album would have been better. We felt like we were going to do another Liberty Belle. But it was a highwater mark. Does that make Oceans Apart a fitting last record? I know it’s not a very generous answer, but it’ll do.

ROBERT FORSTER

SONGS TO PLAY

TAPETE 2015

Grant McLennan died of a heart attack at home in Brisbane, May 2006. Forster made one sombre solo album (The Evangelist, 2008), then put his musical career mostly on hold. New alliances with younger musicians from the John Steel Singers, however, produce this summer’s exceptional Songs To Play, an album in the spirit of Danger In The Past and Rachel Worth.

I knew what this record would be very early on. I had a list of things in my head that I wanted to do, and the problem with The Evangelist was that I couldn’t play any of those songs live. Grant had written a few of them, and there were keys that I could do in the studio but found hard live. I remember playing “From Ghost Town” once, and the audience was just so shocked and so down, I felt like I was choking.

I had the songs ready by 2010, but I couldn’t have come out two years after The Evangelist and said, ‘Everything is different now!’ The songs are bouncy, and time’s got to do its trick. You need to set the scene. The good thing is I had the conviction to record the songs in the way that I wanted to. I wanted to record analogue, and both Ocean’s Apart and The Evangelist were recorded by Mark Wallis with Pro Tools. I didn’t want a computer in the room. I didn’t want to work with Glenn and Adele – they’d moved down to Sydney anyway, and it wasn’t practical to fly them up to rehearse because I didn’t have the money.

And I wanted to record with my wife, who I’d been playing with in the kitchen for 20 years. We’d played a few shows in Germany, then The Go-Betweens and the children got in the way. So digital was over, Glenn and Adele was over, there was distance now from Grant’s death. I guess I was brave enough to follow a couple of decisions through.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.