What happened to David Bowie in 1974? He’d started off the year every inch the feted English pop artist – finishing off his Orwellian concept opera, producing Lulu and playing sax for Steeleye Span. He ended it releasing a cover of Eddie Floyd’s “Knock On Wood”, recording with Philly’s finest and hanging out with Lennon and Springsteen. Even by Bowie’s standards, the transformation from the cover of Diamond Dogs – flame-haired, sci-fi man-hound – to Young Americans – louche lovechild of Sinatra and Dietrich – beggared belief. Was it simply, as producer Tony Visconti suggested, that David was essentially a mod at heart, and he finally had the confidence to make the R’n’B record he always wanted to? Was it, as Bowie himself said to a BBC documentary crew that year, that he’d absorbed American culture through immersion, like a fly floating in milk? Or was it all just a cynically executed plot to seduce and conquer the country that had so far resisted his manifold charms? It’s likely that even Bowie was unsure of his exact motivation when, cracked as the Liberty Bell, he entered Philadelphia’s Sigma Studio (home of hitmakers Gamble and Huff and resident band MSFB) in August 1974 and spent 12 days creating “plastic soul” – his cocktail of gilded funk, swooning strings and heat haze saxophone, shaken and stirred by the anxieties of the post-Nixon USA and delivered as though he was finally letting his pierrot mask slip. As he swooned on the title track: “Ain’t there one damn song that make me break down and cry?” Ironically, the number one single the album yielded, “Fame”, was recorded later in New York, with the help of new pal John Lennon and guitarist Carlos Alomar, from a riff stumbled on while jamming through The Flares’ “Footstompin’”. The bookends of “Fame” and “Young Americans” are undoubtedly the high points here, but, dirgey trawl through “All Across The Universe” apart, the whole record stands up incredibly well. Above all, you realise just how influential the luxurious sound and anxiously ambitious rhetoric – of aspiration, fascination and celebrity – was on a whole generation of upwardly mobile ‘80s pop aesthetes. This latest edition appends a couple of well-known off-cuts (“John, I’m Only Dancing (Again)” and “Who Can I Be Now?”), some 5.1 audio mixes by Visconti, and an appearance on US TV, but the main draw is the previously unreleased, orchestrated “It’s Gonna Be Me”, a synthetic gospel number which suggests that even Prince might have taken a thing or two from this splendidly troubled funk confection. STEPHEN TROUSSÉ

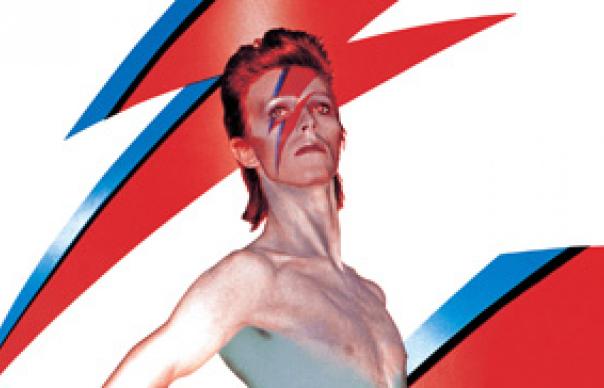

What happened to David Bowie in 1974? He’d started off the year every inch the feted English pop artist – finishing off his Orwellian concept opera, producing Lulu and playing sax for Steeleye Span. He ended it releasing a cover of Eddie Floyd’s “Knock On Wood”, recording with Philly’s finest and hanging out with Lennon and Springsteen. Even by Bowie’s standards, the transformation from the cover of Diamond Dogs – flame-haired, sci-fi man-hound – to Young Americans – louche lovechild of Sinatra and Dietrich – beggared belief.

Was it simply, as producer Tony Visconti suggested, that David was essentially a mod at heart, and he finally had the confidence to make the R’n’B record he always wanted to? Was it, as Bowie himself said to a BBC documentary crew that year, that he’d absorbed American culture through immersion, like a fly floating in milk? Or was it all just a cynically executed plot to seduce and conquer the country that had so far resisted his manifold charms?

It’s likely that even Bowie was unsure of his exact motivation when, cracked as the Liberty Bell, he entered Philadelphia’s Sigma Studio (home of hitmakers Gamble and Huff and resident band MSFB) in August 1974 and spent 12 days creating “plastic soul” – his cocktail of gilded funk, swooning strings and heat haze saxophone, shaken and stirred by the anxieties of the post-Nixon USA and delivered as though he was finally letting his pierrot mask slip. As he swooned on the title track: “Ain’t there one damn song that make me break down and cry?”

Ironically, the number one single the album yielded, “Fame”, was recorded later in New York, with the help of new pal John Lennon and guitarist Carlos Alomar, from a riff stumbled on while jamming through The Flares’ “Footstompin’”. The bookends of “Fame” and “Young Americans” are undoubtedly the high points here, but, dirgey trawl through “All Across The Universe” apart, the whole record stands up incredibly well. Above all, you realise just how influential the luxurious sound and anxiously ambitious rhetoric – of aspiration, fascination and celebrity – was on a whole generation of upwardly mobile ‘80s pop aesthetes.

This latest edition appends a couple of well-known off-cuts (“John, I’m Only Dancing (Again)” and “Who Can I Be Now?”), some 5.1 audio mixes by Visconti, and an appearance on US TV, but the main draw is the previously unreleased, orchestrated “It’s Gonna Be Me”, a synthetic gospel number which suggests that even Prince might have taken a thing or two from this splendidly troubled funk confection.

STEPHEN TROUSSÉ