After spending most of the past 30 years working with a global cast of musicians – Mexican accordionists, Malian griots, Cuban soneros, Hawaiian slack key guitarists, Indian veena players – Ry Cooder’s return to his native LA with 2005’s Chavez Ravine came as something as a surprise. But even this operatic journey through the city was a cunningly disguised ‘world music’ album – using various antique Latin genres to document the Mexican barrios of the 1940s. Now My Name Is Buddy sees the master guitarist return to the vintage US roots music that he seemed to have jettisoned after 1979’s Bop Till You Drop. At the time he dismissed the “sterile archivism” of his 1977 ragtime album Jazz and, to avoid sounding like a worthy ethnomusicologist, Cooder uses his source materials to tell a compelling story. The ‘Buddy’ of the album title comes from a picture of a ginger cat, around whom Cooder developed a backstory. Buddy was not just red-haired, figured Cooder, but politically red – a hobo, a roustabout, a militant union activist – and his picaresque rambles are a journey through the disappearing world of US organised labour. Accompanied by a beautifully illustrated CD booklet, Buddy is joined by a comic-book cast – he befriends a politicised mouse called Lefty (“little but big minded – and he can read!”), and a blind black preacher called the Revd Tom Toad, and fights an evil pig called J Edgar (“Oh J Edgar, just look what you’ve done/you ate up all the cherry pie that was for everyone”). Musically, the guests (Van Dyke Parks, jazz pianist Jacky Terrason, avant trumpeter Jon Hassell, as well as Cooder regulars Jim Keltner, Flaco Jimenez and Ry’s son Joachim) take us through Southern gospel, hillbilly bluegrass and lounge jazz, while the godheads of leftist US folk, Mike and Pete Seeger, provide ideological ballast (and some mean banjo). As a homage to a collectivist America that was all but extinguished by the likes of J Edgar Hoover and Joseph McCarthy, it’s frequently wistful, sad and nostalgic. Yet Cooder’s eccentric storytelling style and his prankish, Sufjan Stevens-ish take on Americana also sounds oddly contemporary. JOHN LEWIS

After spending most of the past 30 years working with a global cast of musicians – Mexican accordionists, Malian griots, Cuban soneros, Hawaiian slack key guitarists, Indian veena players – Ry Cooder’s return to his native LA with 2005’s Chavez Ravine came as something as a surprise. But even this operatic journey through the city was a cunningly disguised ‘world music’ album – using various antique Latin genres to document the Mexican barrios of the 1940s.

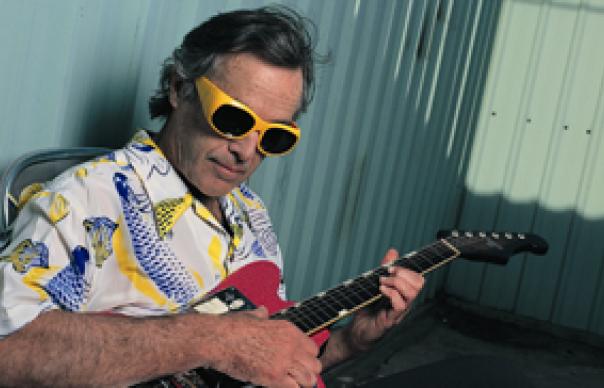

Now My Name Is Buddy sees the master guitarist return to the vintage US roots music that he seemed to have jettisoned after 1979’s Bop Till You Drop. At the time he dismissed the “sterile archivism” of his 1977 ragtime album Jazz and, to avoid sounding like a worthy ethnomusicologist, Cooder uses his source materials to tell a compelling story.

The ‘Buddy’ of the album title comes from a picture of a ginger cat, around whom Cooder developed a backstory. Buddy was not just red-haired, figured Cooder, but politically red – a hobo, a roustabout, a militant union activist – and his picaresque rambles are a journey through the disappearing world of US organised labour. Accompanied by a beautifully illustrated CD booklet, Buddy is joined by a comic-book cast – he befriends a politicised mouse called Lefty (“little but big minded – and he can read!”), and a blind black preacher called the Revd Tom Toad, and fights an evil pig called J Edgar (“Oh J Edgar, just look what you’ve done/you ate up all the cherry pie that was for everyone”).

Musically, the guests (Van Dyke Parks, jazz pianist Jacky Terrason, avant trumpeter Jon Hassell, as well as Cooder regulars Jim Keltner, Flaco Jimenez and Ry’s son Joachim) take us through Southern gospel, hillbilly bluegrass and lounge jazz, while the godheads of leftist US folk, Mike and Pete Seeger, provide ideological ballast (and some mean banjo). As a homage to a collectivist America that was all but extinguished by the likes of J Edgar Hoover and Joseph McCarthy, it’s frequently wistful, sad and nostalgic. Yet Cooder’s eccentric storytelling style and his prankish, Sufjan Stevens-ish take on Americana also sounds oddly contemporary.

JOHN LEWIS