A few years ago, around the time of Sky Blue Sky, Uncut asked Jeff Tweedy for his thoughts on Americana. He had a few. “I’ve never had the fuckin’ slightest clue as to what it means,” he replied. “I’ve been a reluctant participant at best, and a violent contrarian more often, to that lab...

A few years ago, around the time of Sky Blue Sky, Uncut asked Jeff Tweedy for his thoughts on Americana. He had a few. “I’ve never had the fuckin’ slightest clue as to what it means,” he replied. “I’ve been a reluctant participant at best, and a violent contrarian more often, to that label.” Tweedy said much more in that vein, before suggesting that: “Americana is just a fundamentalist reactionary stance to the modern world. It’s imagining some pure, altruistic past that does not exist. It’s a desperate grasp for authenticity, that you either have or you don’t have. Ultimately, it’s either a good song or it’s a bad song. Or: ‘That guy can sing, and when he sings, it makes me feel great.’”

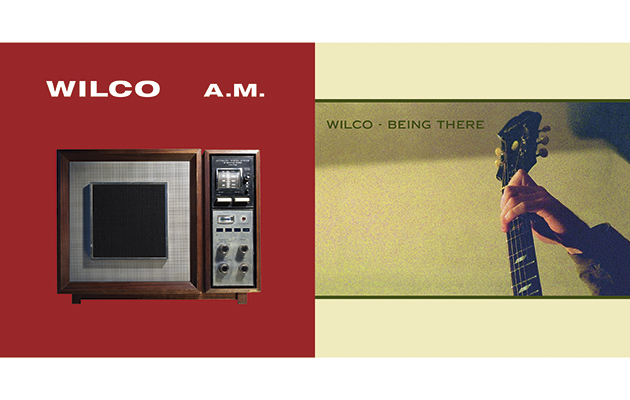

AM, Wilco’s first album, can be seen as an argument about Americana. It was recorded quickly, in Memphis, almost before the dust had settled on Jay Farrar’s decision to split Uncle Tupelo after a hostile final tour in 1994. Uncle Tupelo, of course, were a cornerstone of alt.country, delivering the imagery of Steinbeck with the splattered urgency of punk. It had started out as Farrar’s band, but Tweedy made a vital contribution. The fact that his input was growing in significance may have been a factor in the split, just as the group seemed poised to make a commercial breakthrough.

What, then, would Wilco sound like? There was some continuity of personnel. Tweedy took drummer Ken Coomer, bassist John Stirratt and multi-instrumentalist (dobro, fiddle, mandolin player) Max Johnston with him, as well as offering a guest slot to steel guitar player Lloyd Maines, who had played on Uncle Tupelo’s swansong, Anodyne. The other guest player, Brian Henneman (of The Bottle Rockets) pulled the sound in another direction, bringing a more straightforward rock’n’roll energy. At the time of its release, AM was seen as a continuation of the work done in Uncle Tupelo, and that was how it was designed. It is a conservative record, made in a rush. But it has aged well, and it’s clear that the process of getting it done helped to set the template for how Wilco would function in the future.

There is, at the outset, a gap between the plan and the delivery. There was talk in those early days, and some effort made, to make sure that Wilco functioned more democratically than Uncle Tupelo had. That’s not exactly what happened. John Stirratt supplied three songs for the record, but only “It’s Just That Simple” made the cut. It’s a gorgeous song, a pained lament in the style of The Flying Burrito Brothers; the vulnerability of Stirratt’s voice floated over Maines’ steel guitar. Is it too alt.country? Too Americana? Too Uncle Tupelo? Otherwise, you have to wonder why another fine Stirratt tune, “Myrna Lee”, wasn’t selected. The song emerged on an album by Blue Mountain (featuring Stirratt’s sister Laurie) in 1997. It’s included here, and is one of the finest things on the record. The same holds for “When You Find Trouble”, said to be the last studio recording made by Uncle Tupelo. It’s like Keith Richards singing country: stately, and collapsing.

But AM is about something else. It’s about Tweedy finding a voice, and edging his songwriting from the generic to the personal. Some of the generic efforts are successful. “Pick Up The Change” is a beautiful break-up song, with a tune that never aspires to be more than a busk. “That’s Not The Issue” is a love song for banjo that opens with the writer observing the moon, before dissolving as Tweedy complains of being a songwriter who has run out of metaphors. On “I Must Be High”, Tweedy starts to master the air of weary disdain which will colour so many of his songs. “Box Full Of Letters” is a lovely rush, another break-up song, which some insist is aimed at Farrar, largely because of the verse about giving back some borrowed records. But the song is more notable for its sense of writerly confusion. “I just can’t find the time,” Tweedy sings, “to write my mind, the way I want it to read.” And there’s nothing finer than “Dash 7”, a poetic, mysterious paean to a jet plane landing (Tweedy has not, after all, exhausted his stock of metaphors).

The remaining unreleased tracks are the stodgy “Those I’ll Provide”; “Lost Love” and “She Don’t Have To See You” (both emerged later on Golden Smog albums); an early pass at “Outtasite – Outta Mind”; the punk country of “Piss It Away”, and “Hesitation Rocks”, a stolid attempt at a rock anthem.

Ken Coomer tells a story about the first time Wilco heard Trace, Jay Farrar’s first album with Son Volt. Wilco were in a van and listened in silence. At the end, the band’s manager, Tony Margherita wound down the passenger side window and threw the disc into the street. Trace, says Coomer “lit a fire under somebody’s butt, to be: ‘Hey, we can do better than we did.’”

On Being There, Wilco did better. The addition of Jay Bennett allowed the band to stretch in different directions, and his skill with overdubbing (a necessity in his band Titanic Love Affair) brought an experimental pop sheen to the record. Ultimately, Bennett would threaten Tweedy’s role as the group’s benign dictator, but here he gives him wings. There are country moments – the frisky “Forget The Flowers”, the plangent shuffle of “Far Far Away” – but Being There is the sound of a band inventing its own creativity. The squall of noise that opens the album, leading into “Misunderstood”, on which the band swapped instruments, is the sound of a group of musicians who have finally begun to understand their purpose.

The glories of Being There don’t need to be restated. Arguably, it is Wilco’s best record. Certainly it is a joyous, celebratory thing, the sound of a band in full spate. Previously it was a tight, 19-track set. Here, it sprawls (on 4LP and 5CD versions). There are a number of alternate takes that show paths not taken. “Dynamite My Soul” is a fine Tweedy folk song, “Losing Interest” is a comic blues song (about blues songs) delivered with Lou Reed-ish disdain, there’s an early run at “Capitol City”, and “Sun’s A Star” is an intimate strum, on which the singer employs cosmic imagery to circle around loneliness.

Also included is a live set from the Troubadour (previously issued as a promo cassette) and four songs performed on KCRW from the same period. They show that Wilco’s creativity didn’t stop at the studio door. The songs explode with verve. “Passenger Side” is delivered in punk and regular versions. “Kingpin” meanders over nine minutes before speeding into a wall. “New Madrid” shuffles sweetly towards romantic oblivion. The KCRW session includes a fine “Sunken Treasure”, that ebbs and flows over seven minutes of weary resilience as Tweedy details the ways in which music saved his life. It’s classic Jeff: self-aware, struggling to create a new language with old words. Maimed, tamed, named by rock’n’roll, though not necessarily in that order.