Unsigned and – at that stage – unsignable, their original drummer Dexter Lloyd about to jump ship to join the pit band for Aladdin at the Oxford Playhouse, Roxy Music did not lack a certain chutzpah when they spoke to Melody Maker’s Richard Williams in July 1971. “The average age of this ban...

Unsigned and – at that stage – unsignable, their original drummer Dexter Lloyd about to jump ship to join the pit band for Aladdin at the Oxford Playhouse, Roxy Music did not lack a certain chutzpah when they spoke to Melody Maker’s Richard Williams in July 1971. “The average age of this band is about 27, and we’re not interested in scuffling,” said frontman Bryan Ferry, adamant that ‘Roxy’ felt no need to pay any musical dues. “If someone will invest some time and money in us, we’ll be very good indeed.”

Snooty and ambitious from the off, Ferry’s claim on their day-glo debut single “Virginia Plain” that Roxy had “been around a long time, just try try try tryin’ to make the big time” was something of a canard. The art-rock pioneers were barely road-tested by the time they signed to Island in spring 1972, a perceived disdain for their craft nettling detractors almost as much as Ferry’s ludicrously mannered vocals and the defiantly anti-prog credits for clothes, makeup and hair on the sleeve of their debut LP. Introducing them on The Old Grey Whistle Test a matter of days after Roxy Music’s release on June 16, ‘Whispering’ Bob Harris dismissed the band’s giddy racket as overhyped and amateurish. “Poor old Bob,” guitarist Phil Manzanera told Uncut, inclined to be generous with the benefit of hindsight. “Some people didn’t get it.”

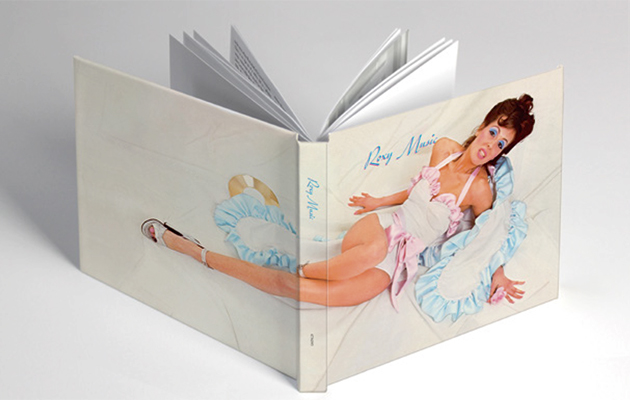

Attempting to digest this four-disc post-mortem on what is still a mightily confusing record, it is easy to sympathise. Demos, outtakes, BBC sessions, a live recording and video footage document Roxy Music’s evolution from bedroom boffins to the crushed-Velvet Underground, but Roxy Music itself remains an assault on the senses to match its era-defining sleeve. Like the music within, cover star Kari-Ann Muller simultaneously seduces, snarls and sneers. Faced with relentless opening track “Re-Make/Re-Model”, as part of Melody Maker’s Blind Date feature in mid-1972, Slade guitarist Dave Hill summed up the vibe fairly well: “There are a lot of influences in it. This must be a very mixed-up band. I don’t know who it is, but it’s very interesting.”

The confidence of Roxy Music’s visual presentation disguised the postmodern jumble at their core. Formed in late 1970 by art-school fop Ferry and his bandmate from Newcastle clubland, bassist Graham Simpson, Roxy Music piled on layers of weird by enlisting oboist Andy Mackay and sound sculptor Brian Eno. Reconciling their reverence for the classic and the kitschy – Noël Coward and the skinny Elvis – with their taste for harsh pop-art brights and electronic noise was to be a long-term challenge.

Larval versions of “Ladytron”, Humphrey Bogart homage “2HB”, “Chance Meeting” and World War II mini-musical “The Bob (Medley)” culled from their mid-1971 home demo – featuring bluesy guitarist Roger Bunn and the tricksy Lloyd – are otherworldly but convoluted. The arrival of another of Ferry’s Geordie-land cohorts, drummer Paul Thompson, beat some of the prog out of them, but the appointment of ex-Nice guitarist Davy O’List brought more old-world clutter, Hendrix licks overloading songs reworked for a BBC session Roxy recorded as an unsigned act at the start of 1972. The lengthy take of the moody “Sea Breezes” is odd, dissonant and anguished, but it’s still King Crimson in brothel creepers.

It is only with the arrival of the 21-year-old Manzanera – mere weeks before the recording of the debut album – that Roxy Music stop sounding like three bands playing at once, though ex-Crimson man Peter Sinfield did not remember the March 1972 sessions that produced the record being particularly slick. “The lack of technical ability made life difficult,” he told one Roxy biographer. Eno and Ferry were non-musicians, Manzanera was “a fairly basic guitarist” and soon-to-be ex-bassist Simpson – suffering some kind of acid-inspired nervous collapse, seemingly brought on by the death of his mother – “kept bursting into tears”.

Such raw emotions were anathema to the Roxy Music that emerged on the finished record; Ferry notably pronounces the word “cry” on “Sea Breezes” like an alien tourist reading from a phrasebook, while ‘love’ Ferry-style is fleeting, illusory – a pursuit rather than a passion. “Re-Make Re-Model” sums it up, its Marcel Duchamp readymade chorus, “CPL 593H”, the number- plate of a red Mini Ferry tracked to a street just off Knightsbridge after falling for its owner at the Reading Festival. Ferry’s breakneck stalking of his horsey dream girl morphs into a garish showcase for Roxy Music’s glossy brand of retro-futurism, with all the individual members taking an ironic mini-solo towards the end – Simpson’s, notably, a cheeky lift of The Beatles’ “Ticket To Ride”.

Women and machines get mixed up again on “Ladytron”, Ferry – perhaps not quite the ladies’ man he would like to be – fantasising about hacking his quarry’s source code (“I’ll use you and I’ll confuse you and then I’ll lose you”), before the song dissolves into an orgiastic extended threesome of distorted Manzanera guitar, Mackay oboe and Eno-tronics.

The rest of Roxy Music lacks that throbbing intensity, but is no less perverse in its pursuit of the impossibly picture-perfect. The devotion imagined on hellbound hoedown “If There Is Something” is so demented it can only be a mocking pastiche, Ferry pledging his ardour with a ludicrous promise to “sit in the garden, growing potatoes by the score”.

Bizarre doo-wop closer “Bitter’s End” is the crystallisation of all of Ferry’s Brill Building fantasies, with a killer self-referential pay-off line (“should make the cognoscenti think”), but the relatively restrained “2HB” may be Roxy Music’s spiritual core. Ferry’s homage to Bogart’s aloof portrayal of Rick in Casablanca celebrates not the film’s towering passions but the perfection of a look of manly composure. It’s the quintessence of the early Roxy Music’s cut-and-paste take on pop (“finding not keeping’s the lesson”), their veneration of style over content.

Rave reviews helped Roxy Music creep into the Top 30, but “Virginia Plain” – recorded in July 1972, and retro-fitted rather gauchely into the album’s running order here – swiftly rendered the whole record obsolete. Ferry’s pop-art slideshow lyrics took Roxy back to square one, plotting a course from their signing a deal with Island (the Robert E Lee referenced in the first verse was apparently Ferry’s lawyer) into a projected world of unending exotic scene-shifts. Boasting perhaps the greatest intro and outro in pop, it ditches the arch twists of the album to become something unequivocally future-facing: a promise to reinvent glamour rather than just recreate it.

A renewed sense of purpose and optimism course through the BBC session version of “Virginia Plain” recorded that summer, Manzanera helping himself to a rapturous screaming guitar solo, and the usually restrained Ferry letting out a gentle yelp in the background. The video and live performances following the single’s ascent to No 4 in the charts in August 1972 capture a band suddenly sure of foot and eager to move on.

Roxy Music – the way Eno saw it – represented a dozen future directions for rock, the best of which were pursued on 1973’s unmissable double feature, For Your Pleasure and Stranded. The lack of “scuffling” in Roxy’s early days may explain why their debut still sounds like work in progress, but the sense of crystallising promise shines through this set. Not brilliant just yet, but very good indeed.

Like us on Facebook to keep up to date with the latest news from Uncut