Influential almost as much for its legend as its actual music, David Bowie’s ‘Berlin trilogy’ of 1977-79 reaches further afield than the name might suggest. Not that the city didn’t give Bowie enough to work with. “Heroes”, with its monochrome cover portrait, Brian Eno’s synthesiser st...

Influential almost as much for its legend as its actual music, David Bowie’s ‘Berlin trilogy’ of 1977-79 reaches further afield than the name might suggest. Not that the city didn’t give Bowie enough to work with. “Heroes”, with its monochrome cover portrait, Brian Eno’s synthesiser strategies and Robert Fripp’s metallic guitars – all recorded at Hansa By The Wall studios under the gaze of an observation tower – was the sort of aesthetic to capture the imagination of a generation.

Bowie in Berlin is a mesmerising, if slightly chilly story, which his 2013 comeback single, “Where Are We Now?” with its mention of his old haunts, only helped reinforce. After psychologically imperilling himself in Los Angeles while dominating the American market, the singer removes himself to a European city, and rents a flat. By day he explores by train and bicycle, and makes music with exciting new collaborator Brian Eno. Iggy Pop comes along. At night, Bowie drinks beer in the city’s working men’s clubs.

As powerful as is that tale of rude health, other interesting truths lie nearby. An artist whose entire career was about the journey, not the getting there, Bowie was never musically more elusive and personally in transit than in the period covered here, when he was supposedly in one place. While “Heroes” is a true Berlin album, Low, his greatest, was largely recorded in France, during depression and marriage crisis. It was effectively homeless: unwelcomed by his record company, unfavourably reviewed and completely unpromoted save for a brief stint while Bowie was appearing as Iggy Pop’s keyboard player. Lodger, the third of the trilogy, was recorded in Switzerland and finished in New York.

More importantly, much of what is contained, remastered, in this new five-year box suggests how these geographical movements were accompanied by musical ones. The haunting abstractions, insistent pulses and wordless vocalisations of “Weeping Wall”, “Warszawa” (and elsewhere on the instrumental sides of Low and “Heroes”) are suggestive not so much of one place, but of something more allusive – the transit between them, of communications between points in a bright technological present.

The beautiful “Subterraneans”, say, reaches back to America (it originates from the aborted Man Who Fell To Earth soundtrack sessions with Paul Buckmaster in late 1975) and on into Europe and the future. It’s not only the instrumentals, either. While Bowie’s European move effected a geographical cure for his cocaine use, the thrilling novelty of the technological R&B which he birthed on Station To Station was not something he would have wanted to leave behind. Here it gave birth to stark and original modern music like “Speed Of Life” and “Blackout”.

Promoting Lodger, Bowie was himself quite carried away with the idea of travel. As he explained, the new album might easily have been called (alongside more immediately Eno-inspired titles like ‘Planned Accidents’) ‘Travel Along With Bowie’. For sure, it got around a bit. This was an album with Turkish reggae with violin courtesy of Simon House from Hawkwind (“Yassassin”), reference to former Luftwaffe pilots drinking in Mombasa (“African Night Flight”), and to spousal abuse in suburban America (“Repetition”).

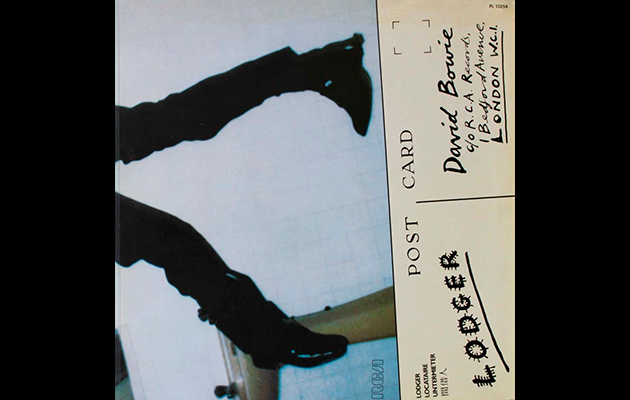

An odd choice, arguably, but Lodger is the big selling point in this box. A commercial stiff before the major upturn in fortunes that came with the excellent Scary Monsters (also here, alongside Japan-only single “Crystal Japan”, the music for Bowie’s TV ad for sake), it was allegedly a personal favourite of Bowie’s. Prevented, its luxuriously laminated gatefold sleeve notwithstanding, from becoming anyone else’s by the constricting nature of the production.

In what is anyway an album with a strange running order (it is counter-intuitively back-loaded with the singles), the combination of prolixity and rhythmic busy-ness can make it easy to miss the tunes, wonderfully operatic performances and slightly batty humour (“The hinterland! The hinterland!”) that can ultimately be found there.

Remixed now by producer Tony Visconti (unfairly forgotten in the rush to incorrectly crown Eno, who played and co-wrote some of the songs, as producer of the albums), the album will never reconcile its strange mixture of quirky worldbeat and synth pop, but the Neu! grooves of “Red Sails” and the bizarrely catchy “Move On” (“All The Young Dudes” backwards – try it!) are now allowed to breathe more freely.

Much as the idea of ‘the 1960s’ means more than the strict confinement of a decade, Bowie’s Berlin is more about a state of mind, a population and its thinking than an actual place. Brian Eno and his intellectual playfulness; Robert Fripp’s alien guitar; Tony Visconti’s embrace of meaningful technology. Between them they gave Bowie the materials to build a city larger and more magnificent than anywhere you could hope to find on a map.

Like us on Facebook to keep up to date with news from Uncut.