A few years ago, while writing a cover story on the early years of Blondie for Uncut, I touched briefly on the career of Jean-Michel Basquiat. The piece opened in the mid-Seventies, when America was in the middle of the worst prolonged economic period since the Great Depression. Many of the people I...

A few years ago, while writing a cover story on the early years of Blondie for Uncut, I touched briefly on the career of Jean-Michel Basquiat. The piece opened in the mid-Seventies, when America was in the middle of the worst prolonged economic period since the Great Depression. Many of the people I spoke to described New York at that time as if they were describing a war zone – full of burned out buildings and survivors eking an existence on the margins. Al Diaz, who as Bomb-One was part of New York’s first wave of graffiti writers, remembered, “There was a certain greyness to the city. Physically, the climate was run down. There was a lot of fun stuff going on, but the condition of the concrete – the physical city – was neglected. People gave less and less of a damn about the environment.”

Another eyewitness, Lenny Kaye, recalled “I remember when everything past Avenue A was taking your life into your hands. There’s scary areas… [a] no-go zone where drugs were rampant and buildings were on fire.”

“Everyone dressed like Road Warrior, like they were in battle – which you were,” added the filmmaker John Waters. “It was the perfect look for the time.”

Get Uncut delivered direct to your door – find out how by clicking here!

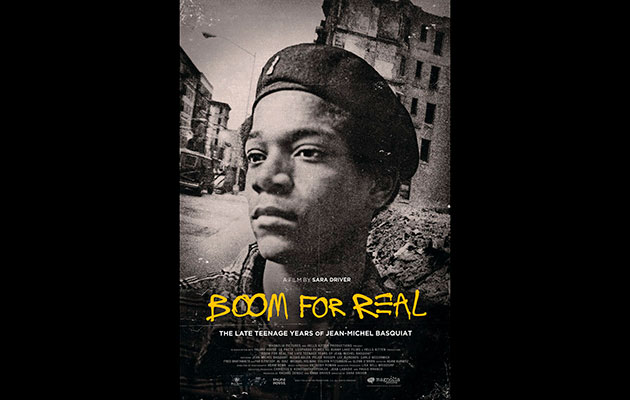

The period has been well-documented, of course – in sources as diverse as the memoirs of Patti Smith and Richard Hell, Amos Poe and Ivan Král’s documentary The Blank Generation and Jonathan Lethem’s novel The Fortress Of Solitude. The latest work to truffle into the Lower East Side of the late Seventies is Sara Driver’s doc, Boom For Real: The Late Teenage Years Of Jean-Michel Basquiat. A one-time NYU film school student, Driver was part of the downtown scene during the Seventies and Eighties when Basquiat rose to prominence. She has rounded up a strong selection of eye-witnesses, too – including her partner Jim Jarmusch, the author Luc Sante, Fred Brathwaite (aka Fab Five Freddy) and Al Daiz.

Jarmusch describes the young Basquiat as a charismatic, if elusive, figure who appears “out of nowhere… and then [he] just disappears.” He tells a story about Basquiat presenting Driver with a rose in the middle of the street – a move that is both bold and impish, very much in line with Basquiat’s wider MO as he tagged provocative SAMO© slogans around the art neighbhourhood, Soho.

Driver also draws on footage from her contemporaries to show the bombed-out Lower East Side – including cuts from rare films by James Nares and Jacob Burckhardt, while Basquiat himself appears often in scenes from Edo Bertolgio’s post-punk snapshot, Downtown 81, which found a semi-fictionalised version of the artist struggling to sell his work.

Brathwaite talks eloquently about “the whole cultural picture” happening in New York at the time, and certainly Driver works in a smart, unshowy way to weave Basquiat into a larger artistic narrative. There is, perhaps, a reason why she doesn’t address Basquiat’s childhood years in private school, or the collapse of his family – instead, we meet him first as a 16 year-old homeless youth, living by his wits, who manages to be everywhere from the Mudd Club to CBGBs, film shows and art exhibitions and all points in between. The artist Sur Rodney (Sur) notes that, without a home or studio, the streets of New York became Basquiat’s place of business; the walls of buildings essentially one giant easel.

One early advocate was Blondie’s Chris Stein, who told me, “No one knew what the fuck was going to happen with Jean. Nobody recognised him early on for being a breakthrough.”

Boom For Real is an excellent addition to Sara Driver’s short but exemplary filmography. Aside from her creative relationship with Jarmusch – she produced Permanent Vacation and Stranger That Paradise and has held credits on many more – she has only directed two feature films: Sleepwalk, a sort-of ghost story set on New York’s nocturnal periphery, and 1993’s When Pigs Fly – a comedy starring Marianne Faithfull as a ghost in pre-gentrified New York. There is also a short, You Are Not I, co-adapted by Jarmusch from a short story by Paul Bowles, the long-lost print of which was recently rediscovered and refurbished in 2012.

At the end of the film, as Suicide’s “Dream Baby Dream” plays over the soundtrack, Jarmusch describes Basquiat a “true investigator”. The same is true of Driver, whose clear-eyed insight assures us not only a rounded portrait of a mercurial artist but of a time and an entire creative scene.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner