For a number of years now – ever since 2015’s Primrose Green, really, a fluid, languid daze of an album, a drifting jazz-folk odyssey – people have been waiting for Chicago singer-songwriter Ryley Walker to make the one, the album that would capture his spirit and essence, that would mark him ...

For a number of years now – ever since 2015’s Primrose Green, really, a fluid, languid daze of an album, a drifting jazz-folk odyssey – people have been waiting for Chicago singer-songwriter Ryley Walker to make the one, the album that would capture his spirit and essence, that would mark him out as one of the greats among his peers – and of his times. It’s something that Walker seems a little uncomfortable with, particularly given his tendency to torch, or at least actively disown, the music of his recent past. In 2016, for example, in an online interview around the release of Golden Sings That Have Been Sung, he pretty much crossed a line out through his early guitar soli and folk song years: “It wasn’t my strong suit. I did that for a few years, and I was like, ‘Goddamnit. Why am I doing this. It’s not me.’”

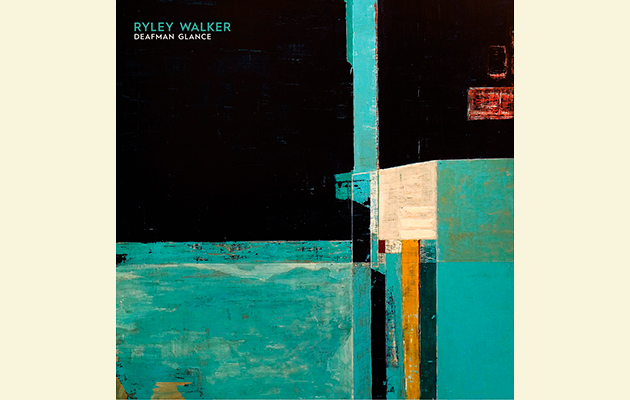

For Walker, locating the self in one’s own music has landed him, in 2018, with Deafman Glance, another album where he’s finding his feet, exploring what’s possible within the new world of song he’s tracking, and enjoying the liberties gifted when you find musicians who really seem to be on your wavelength. There have been a number of diversions, along the way – two lovely collaborative albums with guitarist Bill MacKay, who is central to Deafman Glance, and who released a low-key solo gem, Esker, last year – an album with Chicago jazz drummer Charles Rumback (who’s also played with MacKay), and a guest appearance on Six Organs Of Admittance’s latest, Burning The Threshold.

Get Uncut delivered direct to your door – find out how by clicking here!

But you’d be forgiven for thinking Walker was caught in the complex fug of self-analysis, especially after reading his notes to accompany Deafman Glance, where he’s typically laconic about the struggles of the album’s sessions, and his aims to make something “anti-folk… something deep-fried and me-sounding.” To that end, then, Walker’s succeeded admirably. Deafman Glance picks up the thread he’d laid down with the stronger songs on Golden Sings That Have Been Sung – notably, the tangled beauty of its opener, “The Halfwit In Me” – and moves further forward with its strange, oxymoronic blissed-out tension.

When Golden Sings appeared, both Walker, and particularly critics, talked a lot about the relationships between the album’s songs, and the tricksy, complex structures of Chicago post-rock, groups like Gastr del Sol, The Sea & Cake and Tortoise: music that was in the air when Walker was growing up in Chicago. But he seems to have more fully absorbed the possibilities offered by those groups, now – it’s less about reflecting their sound, and more about understanding the terrain they blasted open, what they made possible within the song. You can certainly here their experimental approach reflected in the open circuits of “Accommodations”, where Walker’s song is blasted open by clattering, tightly scrawled interruptions from flute and synth, the latter played, with a typically deft touch, by Cooper Crain of Bitchin’ Bajas (who also recorded and mixed the album).

But those moments also place Walker’s music down in a much longer historical trajectory, where songs meet freedom, and the edges of structure get beautifully blurred – think of Chris Gantry jamming with folk-jazz trio Oregon; Tim Buckley getting loose on Lorca and Starsailor; the liquid reveries of Willis Alan Ramsey’s lone, self-titled album from 1972, whose voice and writing Walker often recalls. The songs repeatedly spiral out of and back in to focus: “Can’t Ask Why” sends Walker’s humbled melodies out on tinkling percussion and spinning tops of electronic incident; “Telluride Speed” glistens with a kind of limpid melancholy, its lagoon of repose suddenly disrupted by a distinctly prog-esque break, all fast-fingering riffs and descending sequences.

Those moments are often the strongest on Deafman Glance, but not all of the experiments work, still. The cresting structures of “22 Days” feel a bit forced and anti-climactic, and sometimes the playing and writing can get a bit unnecessarily tricksy – not everything here is in service of the song. But those moments are relatively rare. And most often, the compelling moments are where Walker effortlessly manages to balance simplicity and complexity – see “Opposite Middle”, where he, quixotically, finds a weird sweet spot somewhere between The Sea & Cake, Danny Kirwan-era Fleetwood Mac, and Mark Eitzel.

Walker seems to have set himself one of the hardest tasks any artist can ask themselves: what would happen if we let down all our defences and made the art that really resides inside? You can tell that he’s still searching on Deafman Glance, but even its occasional missed steps feel instructive, somehow, as though Walker’s getting closer to the core of the matter, breaking through into new personal terrain. As he himself reflects: “I just wanted to make something weird and far-out that came from the heart finally.”

Q&A

On the first play through of Deafman Glance, I thought, ‘This is a Chicago record.’ How do you connect the city with the songs – what’s the psychogeography of Deafman Glance?

The whole city is a cracked sidewalk with weeds growing out of it. Sort of an off-blue hue to everything. I take long walks at night. There was a lot of inspiration drawn from the frozen-over cold nights. Chicago has everything to do with the tunes.

The team on the album is a motley crew – Chicago jazz players, Cooper Crain of Bitchin’ Bajas… What kind of stew were you wanting to put together when you chose everyone?

Old style, malört, OxyContin, Xanax, cocaine, American spirits, no sleep. Nowadays I prefer red wine and the occasional English breakfast tea.

The album’s come out of a rough patch, for you, and the sessions were tough. Listening back, does the album feel worth the fight? It certainly sounds as though you’ve broken through to somewhere new.

It’s really weird to say “tough” when recording music. I’m stupid lucky to be in a position where indie rock pays the rent. Life is an uphill battle because I so choose it. Music makes the punching bag of reality worth the struggle. It’s all worth it.