Mesmerising trek through the land of Dixie: R Cash paints her masterpiece... Even the lightest-hearted of Rosanne Cash’s superb 35-year repertoire often carries with it the weight of history, the struggle for self-discovery and a sense of place. It’s hardly surprising given her station, born into the first family of American music royalty. On The River & The Thread, Cash’s first album of original material in seven years, and first since brain surgery in 2007, those vibes run deeper than ever, plunging into complicated emotions, impossible situations, piquant insights, fate and history, and the meaning of it all in the land of Dixie. Playing like a travelogue through time, space and place, The River & The Thread opens – with a yawning, bluesy guitar chord – in the northwestern Alabama burg of Florence. This is “A Feather’s Not A Bird”, and it finds Cash flitting between emotional and geographical landscapes to a sinewy, swampy mix of hot-wired guitars, silky harmonies and a revelatory, ominously impassioned vocal. The setting could be right now, or 100 years either direction. “There’s never any highway when you’re looking for the past,” she declares, part of a kind of cumulative taking stock. Cash and guitarist/producer/husband John Leventhal assembled an exemplary lineup of musicians for The River & The Thread: singers Allison Moorer, Amy Helm and John Paul White (The Civil Wars), Allmans guitarist supreme Derek Trucks and, as she puts it, the Voice Of God Choir – Rodney Crowell, John Prine, Tony Joe White, Kris Kristofferson – who pitch in on one cut. That said, it’s Cash, at the top of her game as a singer, who carries the day. Her voice is a persistent wonder, a flexibly crystalline instrument, which with a tiny shift in intonation, a subtle turn of phrase, alters the texture or perspective, imbuing the songs with trenchant, kaleidoscopic shades of meaning. One might think of The River & The Thread as the glorious summation in her post-dad-death trilogy, following 2006’s grief-stricken Black Cadillac and 2008’s tradition-grounded, Johnny Cash-inspired album of covers, The List. It feels as if this is now the point where the internal turmoil subsides, the clouds part, new connections await. Then again, it just might just as easily signal a rather momentous rebirth. Not that there’s not always more grief around the corner. Sung in a kind of stunned mix of determination, vulnerability, and fatalism, “Etta’s Tune” is at the heart of The River & The Thread, indeed the spark, the first piece written for the album. A tribute in part to fallen Tennessee Two bassist and close friend Marshall Grant (a prime architect of her dad’s boom-chicka-boom sound), who passed away in 2011 at 83, and Etta, his wife of 65 faithful years, this song is celebration and mourning. It’s deeply personal yet connected to everything, a glimpse into the fabric of centralising, salt-of-the-earth, real-life characters. Every stanza is teardrop territory. The altogether snappier “Modern Blue” kicks in next, changing up the mood, the album’s shiniest, coolest-rocking coin. Hinging on Leventhal’s catchy guitar curlicues echoing down through the verses, it’s, ostensibly, a world travelers’ tale. The protagonist traipses through a litany of locales, all of them not Memphis, before the epiphany comes: “I went to Barcelona and my mind got changed,” Cash leans into on the song’s pivotal verse, “So I’m heading back to Memphis on the midnight train.” The ghostly blues stomp of “World Of Strange Design”, meanwhile, Trucks percolating the rhythms on slide guitar, is Cash pushing her poetic edge, heading off into deepest mystery, exploring the identity of place, the forces of fate (“If Jesus came from Mississippi…” she ponders), on perhaps the album’s most powerfully affecting track. Along the way, Cash touches upon the quest for spiritualism in a world of loneliness (“Tell Heaven”) and the wits-end desperation of a Dust Bowl-era Arkansas farmer (“The Sunken Lands”). “Night School” feels more contemporary lyrically, but with its sparkling, orchestral 1860s parlor-ballad arrangement, it joins most of its peers in defying the conventional parameters of time; musically, it’s The River & The Thread’s most daring, surprising piece. Foreboding heartbreak permeates the characters’ stark realities in the aching Civil War-era portrait “When The Master Calls The Roll” – the principals scrolling by as in a novel. Within the general structure of a classic Celtic ballad, gorgeous mandolin and fiddle accents, and the her so-called Voice Of God Choir, Cash plunges into myth and reality, magnificence and tragedy, her voice delivering each chapter in the story with an aching beauty. “50,000 Watts”, though, a shuffling blues, grasps new hope, alas a new identity, and optimism in the post-war South – in short, a new start: “We’ll be who we are, not who we were,” she sings in scrumptious, anticipatory harmony with Wandering Sons singer Cory Chisel. The song doesn’t name names, but it might as well be referencing Johnny Cash’s clarion calls “Hey Porter” or “Big River” blasting out of Memphis’ WSM in 1958. The spidery “The Long Way Home” is the album’s sleeper, at first slipping by unsuspectingly. But here, amid a Leventhal string arrangement seemingly awash in kudzu, David Mansfield’s nimble violin and viola touches, and Cash channeling her purest gothic voice, emerges one of the album’s central truths – the resolute inescapability of place: “You thought you’d left it all behind,” she avers. By the time The River & The Thread completes its mesmerising trek, tracing the history and its myriad characters, the feel and the psyche of the deepest South in its closer, “Money Road”, the troupe has arrived in tiny Money, Mississippi, upon a rural roadway adjacent to Robert Johnson’s mythical crossroads. Spooky as a pitch-black midnight walk across Bobbie Gentry’s (also adjacent) Tallahatchie Bridge, Cash’s voice cutting like a scythe through keyboards that rise and fall like ghosts, all the themes, a million micro-bits of the story, converge, before Leventhal suddenly, shockingly, takes the listener out with a prickly electric sitar, time heading in both directions. Luke Torn Q+A Rosanne Cash I have a recent quote from you: “If I never make another album, I’ll be content because I made this one.” Yeah, you know what? That comment is going to come back to haunt me! Well, but I felt it and I feel it. I feel I have been working towards this album for a long time, and I finally wrote some songs I had been trying to reach in myself and outside myself for a long time. I think I was feeling my own mortality when I said that, but it’s pretty true. I do feel that way. Why weren’t you able to reach them before? Well, the last time I wrote an album was seven years ago, my last album was a covers album. A lot happened in that seven years. I think I’m just at the point in my life where these are the songs available to me. This one has a bluesy, swampy feel to it… That was a conscious decision. You know, we decided to make this record about the South and obviously we had to follow some musical direction that made sense for that, and we wanted to cover a lot of territory, everything from that kind of Southern pop, you know Dusty [Springfield] or Bobbie Gentry with the cascading strings thing. Everything from that to really bluesy stuff like “World Of Strange Design”. Then on into “Night School”, which is really more of an orchestral piece – another tradition! …and a sense of being on the road. I mean there’s a lot of geography in the songs, real geography, but I think the thread that goes through it is both real travel and time travel. And the heart opening. When did you first start to write the album, what was the spark? It started to form in 2011. Arkansas State University had purchased my dad’s boyhood home, and they asked me to participate in the restoration and in the fundraising for the restoration. It was really the first Johnny Cash project I had wanted to get involved in. I thought, you know, my dad would really love this, this would be important to him. And it was important to me too, and I thought it would be important to my kids. The house was about to fall down, but they were able to get it. I started organising this fundraiser and while I was down there, Marshall Grant died. That is “Etta’s Song”? Yeah. What was your relationship with Marshall? Oh my God, it was really close. He had become like a surrogate dad to me after my dad’s death. He was the third person to hold me after I was born! We talked every few months. He would go over and over all the stories from the road. He was anguished that he couldn’t prevent my dad’s drug addiction. He remembered all the tours, he’d saved everything, and he was trying to settle his memories. And then he died when I was down there [at Arkansas State], so my heart kinda got cracked open. At the same time I was making a lot of trips down South, and the idea just started to form. And Etta, she was Marshall’s wife for 65 years, she is like family. “The South” is a broad subject. How did you edit? The first way we pared it down was we weren’t going to proselytise, we weren’t going to try to bust any stereotypical myths people have about the South. The songs would be enough, just to point the arrow to the Delta – this is the heartbeat of the country – music, the revolution, the Civil Rights era, the blues, slave songs, gospel, and so much came from there. You think about Bobbie Gentry and Emmett Till, where Till was murdered. The proximity, it was all just right there – where Robert Johnson was buried – it’s all in a few square miles. What came from this experience? That particular trip where we went down Money Road, we took for John’s [Leventhal] birthday, then we went to Oxford, Mississippi, and went to Faulkner’s house, and then deep into the heart of where all the great blues musicians came from – Greenwood, Dockery Farms. We went to Dockery Farms, where Charley Patton had sat on the porch of a juke joint. That in itself was chilling. We met this 90-something-year-old man who knew Bill Faulkner and Eudora Welty, he said [affecting a proper Southern gentleman’s voice], “Eudora was a lovely woman.” And then you add the layer of my own ancestry in Arkansas, and going to the place where my dad grew up, it was just so deep. It was a life-changing experience. What is your favorite track? Well, it depends. “A Feather’s Not A Bird” is real important to me because it lays out the landscape of the whole record. But, some days it’s “50,000 Watts”. It feels like such a heart-opener, looking into the future with so much hope, and knowing everything will be all right. And then some days it’s “When The Master Calls The Roll”, because it feels so timeless to me. I’ve always loved so much those Celtic and Appalachian ballads, story songs, you know, that end in a real heartbreaking way. “World Of Strange Design”, that’s just a great turn of phrase… I was allowing my madness to run riot, free-associative stuff. I thought if I was really in that dense, weird, wonderful South and looking out for a minute – how might my world be, how might it look? Well… Jesus would come from Mississippi. I was able to tap into some madness. Since you spent so much of your upbringing in California, it seems like you are both an insider and an outsider in the South? Exactly. Maybe if I had lived in Money, Mississippi I wouldn’t have been able to do this. You know, I was born in Memphis, I still have a lot of relatives there. There are many layers to this. I can love it freely now, but the first few years I moved away I’d go back and my stomach would start hurting. It would just feel claustrophobic. Now I go back, I’m excited. You know that line from TS Eliot, what is it… “We arrived where we started and know it for the first time”? INTERVIEW: LUKE TORN Photo credit: Clay Patrick McBride

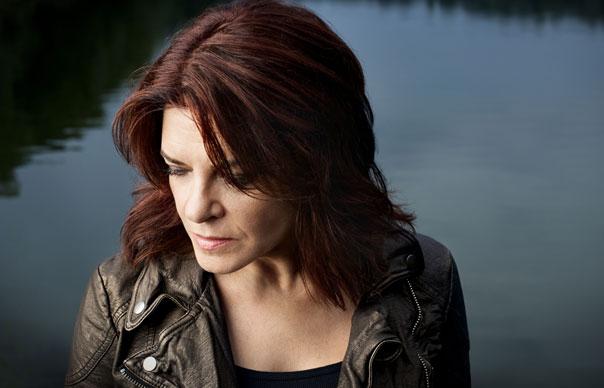

Mesmerising trek through the land of Dixie: R Cash paints her masterpiece…

Even the lightest-hearted of Rosanne Cash’s superb 35-year repertoire often carries with it the weight of history, the struggle for self-discovery and a sense of place. It’s hardly surprising given her station, born into the first family of American music royalty. On The River & The Thread, Cash’s first album of original material in seven years, and first since brain surgery in 2007, those vibes run deeper than ever, plunging into complicated emotions, impossible situations, piquant insights, fate and history, and the meaning of it all in the land of Dixie.

Playing like a travelogue through time, space and place, The River & The Thread opens – with a yawning, bluesy guitar chord – in the northwestern Alabama burg of Florence. This is “A Feather’s Not A Bird”, and it finds Cash flitting between emotional and geographical landscapes to a sinewy, swampy mix of hot-wired guitars, silky harmonies and a revelatory, ominously impassioned vocal. The setting could be right now, or 100 years either direction. “There’s never any highway when you’re looking for the past,” she declares, part of a kind of cumulative taking stock.

Cash and guitarist/producer/husband John Leventhal assembled an exemplary lineup of musicians for The River & The Thread: singers Allison Moorer, Amy Helm and John Paul White (The Civil Wars), Allmans guitarist supreme Derek Trucks and, as she puts it, the Voice Of God Choir – Rodney Crowell, John Prine, Tony Joe White, Kris Kristofferson – who pitch in on one cut. That said, it’s Cash, at the top of her game as a singer, who carries the day. Her voice is a persistent wonder, a flexibly crystalline instrument, which with a tiny shift in intonation, a subtle turn of phrase, alters the texture or perspective, imbuing the songs with trenchant, kaleidoscopic shades of meaning.

One might think of The River & The Thread as the glorious summation in her post-dad-death trilogy, following 2006’s grief-stricken Black Cadillac and 2008’s tradition-grounded, Johnny Cash-inspired album of covers, The List. It feels as if this is now the point where the internal turmoil subsides, the clouds part, new connections await. Then again, it just might just as easily signal a rather momentous rebirth.

Not that there’s not always more grief around the corner. Sung in a kind of stunned mix of determination, vulnerability, and fatalism, “Etta’s Tune” is at the heart of The River & The Thread, indeed the spark, the first piece written for the album. A tribute in part to fallen Tennessee Two bassist and close friend Marshall Grant (a prime architect of her dad’s boom-chicka-boom sound), who passed away in 2011 at 83, and Etta, his wife of 65 faithful years, this song is celebration and mourning. It’s deeply personal yet connected to everything, a glimpse into the fabric of centralising, salt-of-the-earth, real-life characters. Every stanza is teardrop territory.

The altogether snappier “Modern Blue” kicks in next, changing up the mood, the album’s shiniest, coolest-rocking coin. Hinging on Leventhal’s catchy guitar curlicues echoing down through the verses, it’s, ostensibly, a world travelers’ tale. The protagonist traipses through a litany of locales, all of them not Memphis, before the epiphany comes: “I went to Barcelona and my mind got changed,” Cash leans into on the song’s pivotal verse, “So I’m heading back to Memphis on the midnight train.”

The ghostly blues stomp of “World Of Strange Design”, meanwhile, Trucks percolating the rhythms on slide guitar, is Cash pushing her poetic edge, heading off into deepest mystery, exploring the identity of place, the forces of fate (“If Jesus came from Mississippi…” she ponders), on perhaps the album’s most powerfully affecting track.

Along the way, Cash touches upon the quest for spiritualism in a world of loneliness (“Tell Heaven”) and the wits-end desperation of a Dust Bowl-era Arkansas farmer (“The Sunken Lands”). “Night School” feels more contemporary lyrically, but with its sparkling, orchestral 1860s parlor-ballad arrangement, it joins most of its peers in defying the conventional parameters of time; musically, it’s The River & The Thread’s most daring, surprising piece.

Foreboding heartbreak permeates the characters’ stark realities in the aching Civil War-era portrait “When The Master Calls The Roll” – the principals scrolling by as in a novel. Within the general structure of a classic Celtic ballad, gorgeous mandolin and fiddle accents, and the her so-called Voice Of God Choir, Cash plunges into myth and reality, magnificence and tragedy, her voice delivering each chapter in the story with an aching beauty.

“50,000 Watts”, though, a shuffling blues, grasps new hope, alas a new identity, and optimism in the post-war South – in short, a new start: “We’ll be who we are, not who we were,” she sings in scrumptious, anticipatory harmony with Wandering Sons singer Cory Chisel. The song doesn’t name names, but it might as well be referencing Johnny Cash’s clarion calls “Hey Porter” or “Big River” blasting out of Memphis’ WSM in 1958.

The spidery “The Long Way Home” is the album’s sleeper, at first slipping by unsuspectingly. But here, amid a Leventhal string arrangement seemingly awash in kudzu, David Mansfield’s nimble violin and viola touches, and Cash channeling her purest gothic voice, emerges one of the album’s central truths – the resolute inescapability of place: “You thought you’d left it all behind,” she avers.

By the time The River & The Thread completes its mesmerising trek, tracing the history and its myriad characters, the feel and the psyche of the deepest South in its closer, “Money Road”, the troupe has arrived in tiny Money, Mississippi, upon a rural roadway adjacent to Robert Johnson’s mythical crossroads. Spooky as a pitch-black midnight walk across Bobbie Gentry’s (also adjacent) Tallahatchie Bridge, Cash’s voice cutting like a scythe through keyboards that rise and fall like ghosts, all the themes, a million micro-bits of the story, converge, before Leventhal suddenly, shockingly, takes the listener out with a prickly electric sitar, time heading in both directions.

Luke Torn

Q+A

Rosanne Cash

I have a recent quote from you: “If I never make another album, I’ll be content because I made this one.”

Yeah, you know what? That comment is going to come back to haunt me! Well, but I felt it and I feel it. I feel I have been working towards this album for a long time, and I finally wrote some songs I had been trying to reach in myself and outside myself for a long time. I think I was feeling my own mortality when I said that, but it’s pretty true. I do feel that way.

Why weren’t you able to reach them before?

Well, the last time I wrote an album was seven years ago, my last album was a covers album. A lot happened in that seven years. I think I’m just at the point in my life where these are the songs available to me. This one has a bluesy, swampy feel to it… That was a conscious decision. You know, we decided to make this record about the South and obviously we had to follow some musical direction that made sense for that, and we wanted to cover a lot of territory, everything from that kind of Southern pop, you know Dusty [Springfield] or Bobbie Gentry with the cascading strings thing. Everything from that to really bluesy stuff like “World Of Strange Design”. Then on into “Night School”, which is really more of an orchestral piece – another tradition!

…and a sense of being on the road.

I mean there’s a lot of geography in the songs, real geography, but I think the thread that goes through it is both real travel and time travel. And the heart opening.

When did you first start to write the album, what was the spark?

It started to form in 2011. Arkansas State University had purchased my dad’s boyhood home, and they asked me to participate in the restoration and in the fundraising for the restoration. It was really the first Johnny Cash project I had wanted to get involved in. I thought, you know, my dad would really love this, this would be important to him. And it was important to me too, and I thought it would be important to my kids. The house was about to fall down, but they were able to get it. I started organising this fundraiser and while I was down there, Marshall Grant died.

That is “Etta’s Song”?

Yeah.

What was your relationship with Marshall?

Oh my God, it was really close. He had become like a surrogate dad to me after my dad’s death. He was the third person to hold me after I was born! We talked every few months. He would go over and over all the stories from the road. He was anguished that he couldn’t prevent my dad’s drug addiction. He remembered all the tours, he’d saved everything, and he was trying to settle his memories. And then he died when I was down there [at Arkansas State], so my heart kinda got cracked open. At the same time I was making a lot of trips down South, and the idea just started to form. And Etta, she was Marshall’s wife for 65 years, she is like family.

“The South” is a broad subject. How did you edit?

The first way we pared it down was we weren’t going to proselytise, we weren’t going to try to bust any stereotypical myths people have about the South. The songs would be enough, just to point the arrow to the Delta – this is the heartbeat of the country – music, the revolution, the Civil Rights era, the blues, slave songs, gospel, and so much came from there. You think about Bobbie Gentry and Emmett Till, where Till was murdered. The proximity, it was all just right there – where Robert Johnson was buried – it’s all in a few square miles.

What came from this experience?

That particular trip where we went down Money Road, we took for John’s [Leventhal] birthday, then we went to Oxford, Mississippi, and went to Faulkner’s house, and then deep into the heart of where all the great blues musicians came from – Greenwood, Dockery Farms. We went to Dockery Farms, where Charley Patton had sat on the porch of a juke joint. That in itself was chilling. We met this 90-something-year-old man who knew Bill Faulkner and Eudora Welty, he said [affecting a proper Southern gentleman’s voice], “Eudora was a lovely woman.” And then you add the layer of my own ancestry in Arkansas, and going to the place where my dad grew up, it was just so deep. It was a life-changing experience.

What is your favorite track?

Well, it depends. “A Feather’s Not A Bird” is real important to me because it lays out the landscape of the whole record. But, some days it’s “50,000 Watts”. It feels like such a heart-opener, looking into the future with so much hope, and knowing everything will be all right. And then some days it’s “When The Master Calls The Roll”, because it feels so timeless to me. I’ve always loved so much those Celtic and Appalachian ballads, story songs, you know, that end in a real heartbreaking way.

“World Of Strange Design”, that’s just a great turn of phrase…

I was allowing my madness to run riot, free-associative stuff. I thought if I was really in that dense, weird, wonderful South and looking out for a minute – how might my world be, how might it look? Well… Jesus would come from Mississippi. I was able to tap into some madness.

Since you spent so much of your upbringing in California, it seems like you are both an insider and an outsider in the South?

Exactly. Maybe if I had lived in Money, Mississippi I wouldn’t have been able to do this. You know, I was born in Memphis, I still have a lot of relatives there. There are many layers to this. I can love it freely now, but the first few years I moved away I’d go back and my stomach would start hurting. It would just feel claustrophobic. Now I go back, I’m excited. You know that line from TS Eliot, what is it… “We arrived where we started and know it for the first time”?

INTERVIEW: LUKE TORN

Photo credit: Clay Patrick McBride