If there’s one question more perplexing than why Billie Joe McAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge in “Ode To Billie Joe”, it’s what happened to Bobbie Gentry. Some 14 years after her enigmatic hit topped the charts during 1967’s Summer Of Love, Gentry appeared on American TV ...

If there’s one question more perplexing than why Billie Joe McAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge in “Ode To Billie Joe”, it’s what happened to Bobbie Gentry. Some 14 years after her enigmatic hit topped the charts during 1967’s Summer Of Love, Gentry appeared on American TV singing “Mama, A Rainbow” in a 1981 Mother’s Day special. It was her final performance, after which she disappeared from public view as effectively as if she had entered a nunnery.

Sporadic reports suggested that she was living unobtrusively in Los Angeles, although in 2016 the Washington Post claimed she was residing in a gated community in Memphis, a two-hour drive from the Mississippi locations in her celebrated composition.

Even those to whom she was once close don’t know for sure. “I’ve tried every way in the world to get in touch with her, but she won’t accept calls,” her one-time producer Rick Hall reported shortly before his death in 2018. Glen Campbell, her erstwhile singing partner who died in 2017, was also out of contact for years. “We have no idea where she is,” his management told an enquiring journalist. “If you find her, please get her to call us.”

Why she went into seclusion remains a mystery, and Hall’s explanation that her career left her with “a lot of bad memories of the music business” perhaps tells only part of the story.

Her entire recording history lasted just four years, between 1967–71. After that, she spent much of the 1970s on stage in Las Vegas, where a highlight of her show was apparently a gender-bending tribute to Elvis Presley, performed in a glittering, skin-tight pantsuit.

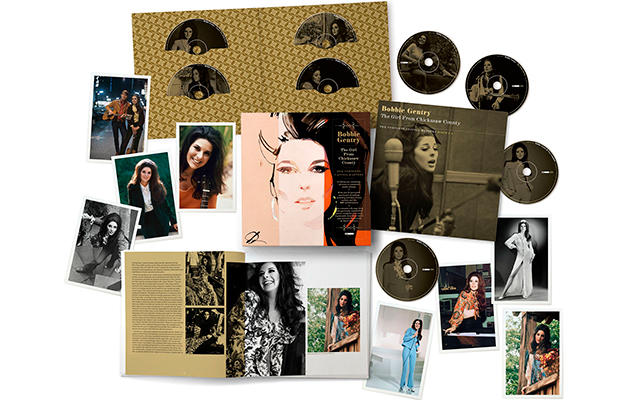

Then she abandoned that too, leaving an impressive legacy – which could surely have been so much greater – now presented for the first time in a comprehensive boxset, comprising remastered versions of her seven studio albums for Capitol, supplemented by a cornucopia of deep cuts, including outtakes, demos, rarities and an eighth disc of live performances taken from her late-1960s BBC television series.

What emerges is a revelation – at least to those who had pegged her as a straight-up country singer all these years. Gentry was actually no more country than, say Tony Joe White, whom she rivals as a Southern gothic storyteller, or Shelby Lynne, who sometimes sounds like a modern-day Gentry clone.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

Gentry’s debut album, Ode To Billie Joe – which ended Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’s 15-week reign at the top of the US charts – is a neglected masterpiece that spans country, folk, soul, pop, jazz and swamp rock. The opener, “Mississippi Delta” – originally the A-side to “Ode To Billie Joe” – choogles like Creedence Clearwater Revival rolling on the river. “Billie Joe” itself hardly needs further comment, except to note that Dylan, holed up in Woodstock with The Band, was so struck by Gentry’s ability to compress the plot of what could have been a novel into a four-minute song that he wrote “Clothes Line Saga” (subtitled “Answer To Ode”) as a riposte.

The album offers further rich vignettes of Southern living on “Chickasaw County Child” and “Lazy Willie”, while her sensual vocal on “Niki Hoeky” is even more erotic than Aretha Franklin’s version on Lady Soul. She followed with 1968’s The Delta Sweete, a dozen songs conceived as a concept about Mississippi life, combining original compositions with covers of “Tobacco Road”, “Big Boss Man” and “Parchman Farm”. The result is an Americana classic.

Under commercial pressure from her record company, Local Gentry, her third album in just 12 months, mixes more Delta myth-making with too many Beatles covers and overly lush arrangements. The suits at Capitol then pushed her into an easy-listening duets album with Glen Campbell that does no justice to her talents at all.

Touch ’Em With Love (1969) again suffers from too many covers, although, as you may imagine, she sings the hell out of “Son Of A Preacher Man”. Fancy (1970) sits firmly in saccharine Bacharach territory, with the rather fine pop-soul of the title track her only writing credit.

Saving the best until last, Patchwork, her 1971 swansong, finds her seizing back control from the label, and is another masterpiece. With the singer writing all 12 of its songs, which are interspersed with instrumental interludes, the influence of Carole King – whose classic set Tapestry had just been released – is evident from the title to the barefooted aesthetic and the troubadour-styled arrangements. At the same time, Gentry’s earthy storytelling ensures this is a tapestry woven not in the Californian canyons, but stitched with the grittier threads of the Deep South. It’s brilliance leaves you lamenting what she might have gone on to achieve if she hadn’t abandoned songwriting and the studio and headed for Vegas.

The previously unreleased material offers further fascinating insights, from the intimate beauty of some of the acoustic demos, to an exquisite cover of “God Bless The Child” from an abandoned acoustic jazz album and – perhaps best of all – “Love Took My Heart And Mashed That Sucker Flat”, a little-known duet with Kelly Gordon that ranks alongside Lee Hazlewood and Nancy Sinatra at their deliciously louche best.

Previously unheard originals such as “I Didn’t Know” and “Joanne” are testament to her storytelling abilities as a songwriter, while the live material shows why she became such a hit on stage in Vegas, equally capable of belting out a soulful “If You Gotta Make A Fool Of Somebody” or delivering a pin-dropping “Ode To Billie Joe”, the song that in many ways started it all.