Anyone who’s ever been to a truly wild party knows that it can be very hard to put on the brakes. That’s what the senators of Rome learned in 186 BC when they officially prohibited the worship ceremonies for Dionysus (or Bacchus, as the Romans called the god of wine and music). Alas, the decree ...

Anyone who’s ever been to a truly wild party knows that it can be very hard to put on the brakes. That’s what the senators of Rome learned in 186 BC when they officially prohibited the worship ceremonies for Dionysus (or Bacchus, as the Romans called the god of wine and music). Alas, the decree was ignored for a few more centuries. It’s not hard to understand why given the lurid accounts of the rites; along with the copious amounts of wine, there were torches and masks, orgies and animal sacrifices, the beating of drums and, of course, plenty of dancing.

Such images are evoked by the most frenzied passages of the new Dead Can Dance album. Yet Brendan Perry and Lisa Gerrard also emphasise the notion that there was a practical purpose for these ancient ragers. Typically held at harvest time, the worship ceremonies marked seasonal cycles of death and rebirth while offering participants fleeting chances for liberation from societal restrictions and transcendence from the self. Aspects of the rites persisted long into Judeo-Christian times, disguised as harvest festivals and pagan celebrations.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

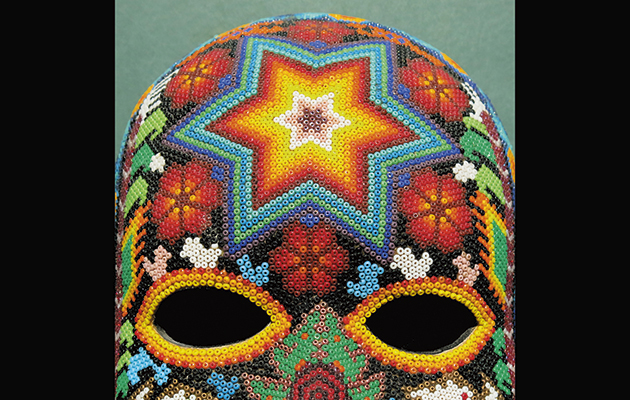

Other religions had their own iterations, a suggestion that Perry makes with Dionysus’s cover image of a mask made by the Huichol, an indigenous people in Mexico. It’s a reference to their similar use of rite and ritual for healing and mind expansion, albeit with the help of peyote rather than the beverage Dionysus concocted. Of course, musicians have done their best to induce these frenzies in more secular contexts. If the cult of Dionysus has any adherents in the present day, then Perry and Gerrard have provided them with the richest possible soundtrack.

Dionysus is the duo’s second album of new material in the seven years since they resumed the partnership that began in Melbourne in 1981 and yielded a string of enigmatic releases for 4AD, earning Dead Can Dance its own fervent cult. Though the gloom that pervades their early albums unfairly led to a goth association, the duo’s imaginative scope far exceeded those of most Batcave dwellers. The ultimate realisation of their pan-global, high-art ambitions, Aion (1990) and Into The Labyrinth (1993), saw them fuse disparate musical traditions (Celtic, Middle Eastern and Mediterranean) into enthralling settings for Gerrard’s spine-chilling mezzo-soprano and Perry’s booming, Scott Walker-like baritone.

Their approach become more staid on the final albums before Dead Can Dance’s original end in 1998. The first new work after the duo resumed their activities in 2011, Anastasis (2012) was also more placid than passionate. Yet Dionysus is not only one of the most vivid works they’ve recorded, it’s also the most intricately and insistently rhythmic. The product of two years’ worth of research and recording as Perry found his own ways to channel the old magic, the album bursts with all the unruly energy its subject matter demands.

Dionysus is constructed as an oratorio that traces the progress of a Dionysian rite while incorporating other elements of the myth. The first of two acts begins with “Sea Borne”, which portrays the god’s arrival with the intensifying sounds of water, drums and voices. By the time the party peaks in “Dance Of The Bacchantes”, what you hear is a head-spinning swirl of trance-music styles, variously evoking Sufi devotional song, Indian raga and Balinese gamelan. Perry compounds the resulting sense of disorientation by using a wide array of instruments, including the daf, a Persian/Kurdish frame drum, and the fujara, a flute favoured by the shepherds of Slovakia. Meanwhile, the abundance of natural sounds melts any boundaries between musical and non-musical elements.

It’s such a riot of the senses, it’s not so surprising the traditional focal point of Dead Can Dance’s music – Gerrard’s voice – has no presence in the album’s early going. But she dramatically comes to the fore in the second act, in which she portrays Dionysus in female form (the god’s androgyny is another key characteristic) and in his/her role as a guide who accompanies souls into the underworld. Named after the Greek term for this last incarnation, “Psychopomp” ends the album in a softer yet still shamanic mode, the serenity of Gerrard and Perry’s duet being all the more startling thanks to the fervour that precedes it. The gentle completion of the ritual also provides a respite from the more aggressive rhythms and compositional complexity that make Dionysus so compelling. And as Gerrard’s voice recedes into the silence, we’re left with the sense that the hungers for mystery and transcendence this music explores could be as fundamental to us as it was to those who partied so hard so long ago.