When a feature film is released 48 years after it started shooting, there’s something to be said against rushing to snap judgements about its merit. And when its director is Orson Welles, whose films have invariably fuelled long-running debate, a thumbs-up-or-down response isn’t necessarily what’s required. So perhaps it’s too soon to know what to make of Welles’s final film, The Other Side Of The Wind – now at long last pieced together, and viewable through Netflix. But what was clear when it was premiered at the Venice Film Festival recently was that this was an extremely modern film by an old-school maestro – and at the same time, for better or worse, a work very much of its time.

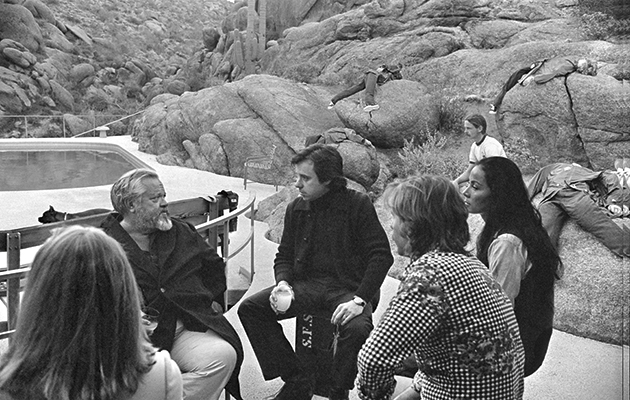

Welles shot the footage piecemeal between 1970 and 1976 – and in its discontinuity, it shows. This is a movie about movies – and inescapably, about Orson Welles. He doesn’t appear, but he has a formidable stand-in: another Hollywood legend, John Huston, playing a celebrated director named Jake Hannaford. The action takes place on the last day of Hannaford’s life, mainly at a party at which his friends, enemies, business associates and various hangers-on assemble to watch fragments of his latest film, entitled – what else? – The Other Side Of The Wind. Hannaford’s movie, hugely stylised and in vivid colour, is an erotic reverie in which a hippie-ish young man (Robert Random) pursues a mystery woman (Welles’s partner and the film’s co-writer Oja Kodar) across an eerie Los Angeles, playing tag with her in and out of deserted sound stages and having a spontaneously torrid encounter in a car.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

During a frenzied car ride, and then at the house of a Dietrich-like actress (Lili Palmer), Hannaford and young critic-turned-director Brooks Otterlake (Welles’s own protégé Peter Bogdanovich) engage in debate with all comers on cinema, notably musing on Hollywood’s past, present and (debatable) future: remember, this was a period when the once unshakeable studio system was contemplating its collapse.

Tentatively edited by Welles for years, the completed film has been pieced together by editor Bob Murawski with producers Filip Jan Rymsza and Frank Marshall (the latter was part of Welles’s original crew), while Bogdanovich is an executive producer. The result is a perplexing hybrid. The black-and-white material, veering between docu-style roughness and chiaroscuro expressionism, mainly comprises the party, its floods of overlapping dialogue evoking John Cassavetes and Robert Altman. It features several filmmakers appearing to all intents and purposes as themselves – among them, Claude Chabrol, Paul Mazursky and a reliably mouthy Dennis Hopper. Also on the mix is a barrel-load of Shakespeare references, some dream surrealism (shop dummies, the mandatory dwarves), and a homosexual subtext involving Hannaford’s male star, who seems to be the director’s real love object.

As for Hannaford’s colour film, it’s dazzling to behold, but looks uneasily like a period piece – partly because of its stylised parody of contemporary art cinema (including Antonioni’s sex- and-desolation epic, Zabriskie Point), partly because of its unreconstructed objectifying of Kodar, naked for much of the time. The footage is deliriously beautiful, however, and it’s a safe bet that cinematographer Gary Graver studied his fair share of Elektra album sleeves.

The Other Side Of The Wind is hard to get a grip on for multiple reasons. One is its super-dense script, its verbal torrents too relentless to be easily assimilated. Another is a fundamental contradiction: on one hand you have Hollywood’s great experimenter, supposedly a dinosaur at the time, energetically reinventing himself for a new age; on the other, there’s no escaping that the hipness of that era’s New Hollywood now itself looks antediluvian in many ways.

We can’t know how much this film really captures of what Welles intended. Would his version have been so breakneck, so fragmented? And what would ’70s viewers have made of the film if he had been completed it? Would it have signaled his return to acclaim as a radical modernist, or sealed his reputation as a Prospero of cinema, washed up on his own distant shore and weaving hermetic spells in exile?

Two things are certain, however. One is that the film stands as a magnificent testimony to cinematographer Gary Graver, who stuck with the project over many difficult years, and whose images crackle with virtuoso invention. The other is that Michel Legrand’s newly added score contributes considerably to the film’s freshness. There’s some contemporary pop and rock mixed in, too – and there’s something irresistibly improbable about an Orson Welles film containing both Tony Hatch’s “Music To Watch Girls By” and proto-metallists Blue Cheer.