Reed and Cale's most experimental work. Still mind-blowing... "No one listened to it," claims Lou Reed in the press release for this reissue of The Velvet Underground's second album. "But there it is, forever - the quintessence of articulated punk." He's only partly correct: Reed's assessment of White Light/White Heat's cultural significance is spot on, but it's not right to say that no one listened to it. My friend Alan and I spent a heady weekend back in 1971 tripping to this colossal record on some ridiculously strong hallucinogen. It was pure liquid acid, dripped onto centimetre cubes of plaster of paris, which you had to keep in the freezer to prevent the drug evaporating. Having chewed and swallowed a cube apiece, we listened to "Sister Ray" at huge volume, pinioned in our chairs. It was my first and only true synaesthetic experience: I could actually see this music, a turbulent, roiling maelstrom in which, though merely mono, the various constituent elements were clearly visible as a three-dimensional sculpture of visual sound. Quite extraordinary. And yet there lies in Reed's remark a grain of truth. For while its predecessor The Velvet Underground & Nico has subsequently become garlanded with legendary status as the Great Influential Album, White Light/White Heat remains comparatively unknown, a secret infatuation esteemed mostly by initiates and obsessives. It's the purer, less compromised of the two records, and the better for it. It's also the Velvets album on which John Cale's input is most significant, both musically and vocally. Where the debut had blended candy pop, modal drones and chugging rock riffs, here the pop element was reduced to just the token two minutes of "Here She Comes Now", a soothing mantra that served as a brief moment of balm amongst the blistering noise, a guttering light in the churning darkness. The rest of the album constitutes one of rock’s great warts’n’all masterpieces - a barrage of heavily distorted, churning riff-noise in which the usual rock influences are given a jolt of speed and a crash-course, courtesy of Cale’s seething organ and viola, in the minimalist experiments of LaMonte Young and Terry Riley. The speed-freak anthem title-track opens proceedings at a shambolic sprint, Reed's hammered piano and the harmony hooks applying a sleek varnish to its oddly sluggish momentum. Then Cale's lugubrious Valley Boy intonation narrates "The Gift", the ghoulish tragi-comic tale of poor Waldo Jeffries' doomed attempt to visit his old girlfriend via the US Mail, a debacle animated over eight minutes by the band's curmudgeonly, rolling groove, which seems to celebrate Waldo's absurd fate with an existential relish. Thanks to this edition's various additions, it's now possible to hear "The Gift" either in mono, the original bi-polar stereo (story to the left, music to the right), as an instrumental, or an unaccompanied story. The new remastering is most effective on "Lady Godiva's Operation", another grim tale sung by Cale as a haunting, distracted lullaby, with startling interjections from Reed. It's now recognisable as the album's most complex sound-montage, containing sound effects - breathing, heartbeat, whispering, moaning - only partly discernible in the muffled original version. The second side opens with "I Heard Her Call My Name", perhaps the single most intensely amphetaminised track ever recorded, a surge of erotic ardour that bursts in, mid-flow, on a spear of piercing guitar, galloping along on the edge of feedback as Reed exults in how a girl's attention makes his "mind split open". It's one of the taproot riffs not just of punk but also Krautrock, a charging motorik that sets up the climactic 17-minute demi-monde tableau of "Sister Ray", another rolling, sluggish riff in which Cale's stabbing organ jousts with Reed's tortured guitar whine, as Mo Tucker and Sterling Morrison's anchoring groove speeds up and subsides beneath an uncoiling, semi-improvised scrawl that owes nothing to the usual blues roots. The subsequent departure of Cale removed the sense of pitched battle from their sound, throwing the spotlight more on Reed’s tales of emotional erosion amongst losers and lovers on the fringes of society. As a result, the Velvets effectively contracted into a dinky little rock’n’roll group, with the aggressive, urban blitzkrieg snarl of White Light/White Heat supplanted by the more intimate style of their eponymous third album, with its recovery-ward air of acquiescence. The cusp of this change is captured in the additional outtakes of "Temptation Inside Your Heart", "Beginning To See The Light", "Stephanie Says", "Guess I'm Falling In Love" and two versions of "Hey Mr. Rain"; but the real bonus here is the complete April 30 1967 show from The Gymnasium, NYC, a tremendously involving performance that captures the Velvets at something like their optimum, from the chugging proto-punk-rock of "Guess I'm Falling In Love" to a 19-minute "Sister Ray" that adds a switchblade panache to the album version. As for my debauched acid weekend, that didn't end well. The next night, I chomped another plaster cube and we went to see Carnal Knowledge, which had just come out. And then my mind split open. Andy Gill Lou Reed: The Ultimate Music Guide is available now. For more details, click here

Reed and Cale’s most experimental work. Still mind-blowing…

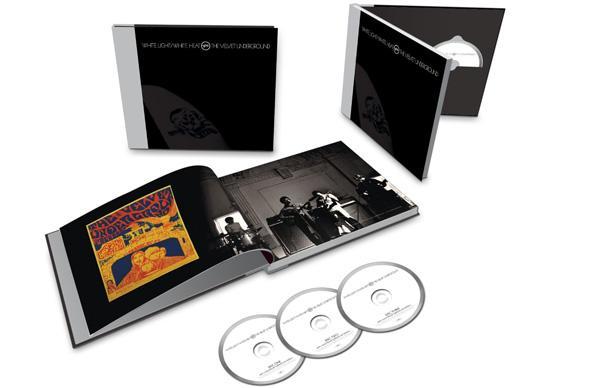

“No one listened to it,” claims Lou Reed in the press release for this reissue of The Velvet Underground’s second album. “But there it is, forever – the quintessence of articulated punk.”

He’s only partly correct: Reed’s assessment of White Light/White Heat‘s cultural significance is spot on, but it’s not right to say that no one listened to it. My friend Alan and I spent a heady weekend back in 1971 tripping to this colossal record on some ridiculously strong hallucinogen. It was pure liquid acid, dripped onto centimetre cubes of plaster of paris, which you had to keep in the freezer to prevent the drug evaporating. Having chewed and swallowed a cube apiece, we listened to “Sister Ray” at huge volume, pinioned in our chairs. It was my first and only true synaesthetic experience: I could actually see this music, a turbulent, roiling maelstrom in which, though merely mono, the various constituent elements were clearly visible as a three-dimensional sculpture of visual sound. Quite extraordinary.

And yet there lies in Reed’s remark a grain of truth. For while its predecessor The Velvet Underground & Nico has subsequently become garlanded with legendary status as the Great Influential Album, White Light/White Heat remains comparatively unknown, a secret infatuation esteemed mostly by initiates and obsessives. It’s the purer, less compromised of the two records, and the better for it. It’s also the Velvets album on which John Cale’s input is most significant, both musically and vocally. Where the debut had blended candy pop, modal drones and chugging rock riffs, here the pop element was reduced to just the token two minutes of “Here She Comes Now”, a soothing mantra that served as a brief moment of balm amongst the blistering noise, a guttering light in the churning darkness.

The rest of the album constitutes one of rock’s great warts’n’all masterpieces – a barrage of heavily distorted, churning riff-noise in which the usual rock influences are given a jolt of speed and a crash-course, courtesy of Cale’s seething organ and viola, in the minimalist experiments of LaMonte Young and Terry Riley. The speed-freak anthem title-track opens proceedings at a shambolic sprint, Reed’s hammered piano and the harmony hooks applying a sleek varnish to its oddly sluggish momentum. Then Cale’s lugubrious Valley Boy intonation narrates “The Gift“, the ghoulish tragi-comic tale of poor Waldo Jeffries’ doomed attempt to visit his old girlfriend via the US Mail, a debacle animated over eight minutes by the band’s curmudgeonly, rolling groove, which seems to celebrate Waldo’s absurd fate with an existential relish. Thanks to this edition’s various additions, it’s now possible to hear “The Gift” either in mono, the original bi-polar stereo (story to the left, music to the right), as an instrumental, or an unaccompanied story.

The new remastering is most effective on “Lady Godiva’s Operation“, another grim tale sung by Cale as a haunting, distracted lullaby, with startling interjections from Reed. It’s now recognisable as the album’s most complex sound-montage, containing sound effects – breathing, heartbeat, whispering, moaning – only partly discernible in the muffled original version. The second side opens with “I Heard Her Call My Name”, perhaps the single most intensely amphetaminised track ever recorded, a surge of erotic ardour that bursts in, mid-flow, on a spear of piercing guitar, galloping along on the edge of feedback as Reed exults in how a girl’s attention makes his “mind split open”. It’s one of the taproot riffs not just of punk but also Krautrock, a charging motorik that sets up the climactic 17-minute demi-monde tableau of “Sister Ray“, another rolling, sluggish riff in which Cale’s stabbing organ jousts with Reed’s tortured guitar whine, as Mo Tucker and Sterling Morrison’s anchoring groove speeds up and subsides beneath an uncoiling, semi-improvised scrawl that owes nothing to the usual blues roots.

The subsequent departure of Cale removed the sense of pitched battle from their sound, throwing the spotlight more on Reed’s tales of emotional erosion amongst losers and lovers on the fringes of society. As a result, the Velvets effectively contracted into a dinky little rock’n’roll group, with the aggressive, urban blitzkrieg snarl of White Light/White Heat supplanted by the more intimate style of their eponymous third album, with its recovery-ward air of acquiescence. The cusp of this change is captured in the additional outtakes of “Temptation Inside Your Heart”, “Beginning To See The Light“, “Stephanie Says”, “Guess I’m Falling In Love” and two versions of “Hey Mr. Rain”; but the real bonus here is the complete April 30 1967 show from The Gymnasium, NYC, a tremendously involving performance that captures the Velvets at something like their optimum, from the chugging proto-punk-rock of “Guess I’m Falling In Love” to a 19-minute “Sister Ray” that adds a switchblade panache to the album version.

As for my debauched acid weekend, that didn’t end well. The next night, I chomped another plaster cube and we went to see Carnal Knowledge, which had just come out. And then my mind split open.

Andy Gill

Lou Reed: The Ultimate Music Guide is available now. For more details, click here