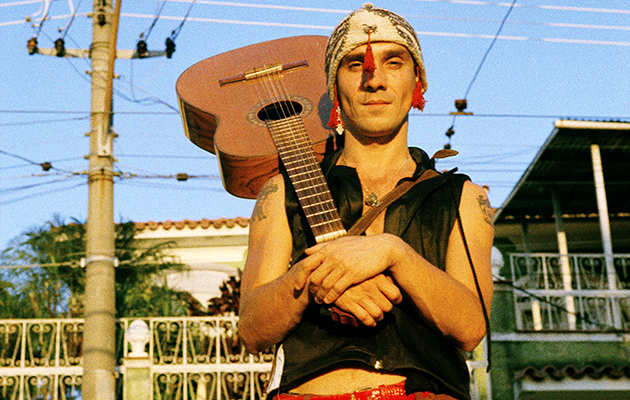

Manu Chao was in a bad way when his band Mano Negra broke up in 1994. Intended as a potent Gallic equivalent of The Clash, after four albums in a turbulent seven years the group had fallen apart in the wake of an insane tour by train across war-torn, bandit-strewn Colombia, dodging bombs and playing impromptu free shows along the way. By the time the train returned to Bogotá six gruelling weeks later, the French-Spanish Chao was the only one left standing. Restless and depressed, he promptly disappeared on a three-year lost weekend, pinballing between Europe, Africa and South America.

He briefly turned up in London, where a musical flirtation with Leftfield promised much but came to nothing, and there were sightings in Paris and Naples. Unable to settle anywhere for more than a few weeks, he next made his way back to Colombia and then to Mexico, where he got out of his gourd on peyote and hung out with the Zapatistas. Then he moved on to Tijuana, where the chaotic energy of the border seemed to suit his mood, before he hit rock bottom in Brazil, where he decided to kill himself.

He claimed that a cow saved his life when it wandered into a desolate beer shack in a run-down Rio favela where he was drinking away his pain. He looked into the cow’s eyes and detected a “tenderness” that made him decide that he wanted to live. He headed back to Europe and landed in Spain, clutching little more than his portable recorder, on which he had been saving the many songs he had written on his travels, intermingled with street sounds, snatches of conversation and other noises of the road. In Madrid and then Galicia he wrote more songs, before making his way to Paris, where he helped former girlfriend Anouk record an album for Virgin. It pushed him into thinking about going back to work and creating his own album from the 50 songs and snatches haphazardly stored on his recorder.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

By the summer of 1997, he had decided which tracks to include but was unsure about the extent to which he wanted to use electronica on the album. In the end the decision was made for him when the software on his computer developed a bug that accidentally stripped out the electronics and the drums. Reportedly, Chao’s only response to this potential catastrophe was to say “le hazard est mon ami”– chance was his friend.

What remained was spare, beautiful, visionary – and more than a little unhinged. If Clandestino sounded unlike anything else one had ever heard on its release in 1998, the closest analogy might to be think of it as a world music equivalent of Skip Spence’s Oar.

Instead of a personal singer-songwriter vibe, Chao created a stoner classic steeped in bouncing global rhythms, full of magical, chiming harmonics and sinuous vocals that weave in and out of the mix in four different languages – Spanish, French, English and Brazilian-Portuguese. The lyrics are full of street slang from the barrios and favelas and oscillate thrillingly between the hilariously surreal (“Bongo Bong”, the album’s best known song, a radical reworking of a Mano Negra track), the bittersweet (“Lagrimas De Oro”), radical politics (“Mentira”) and a beguiling mix of hedonism and despair that drives him to seek redemption in “tequila, sexo, marijuana” (“Buenvenido En Tijuana”).

With Clandestino, Chao created a subversive, multi-lingual global party manifesto that gave voice to the dispossessed and soundtracked a brief but tangible moment of premillennial hope in which it seemed the world was progressively becoming a more tolerant place as we hurtled towards the year 2000. Sadly, times have instead grown darker. Yet if Clandestino captured a moment in time, Chao’s irresistible rhythms and message of resistance continue to sound fresh and vibrant a generation on.

Three bonus tracks bring the story up to date via a cracking reworking of the title track featuring the veteran Trinidadian singer Calypso Rose, new song “Bloody Bloody Border”, which seeks to blow a giant hole in Trump’s wall, and “Roadies Rules”, a new version of a previously unreleased track from the original Clandestino cache.

The album went on to sell more than five million copies around the world, but made little impression in Britain. Perhaps this expanded release will finally redress the balance. In the era of Trump and Brexit, if your faith has been battered by the 21st-century blues, lend Clandestino your ears. It won’t cure anything. But its unique medicine will surely ease the pain.