Six-disc set from the 'identity crisis' years - three albums, outtakes, lives and a session with Freddie King... In his 2007 autobiography, Eric Clapton revealed the unconventional manner in which he prepared for his '74 comeback after three years lost to heroin addiction. As part of his rehabilitation, he went to work on a Shropshire farm owned by Lord Harlech, the father of his then girlfriend Alice Ormsby-Gore, rising at dawn and "working like a maniac, baiing hay, chopping logs, sawing trees and mucking out the cows." While regaining physical and mental fitness, the simplicities of farm life also gave Clapton untroubled space to collect his thoughts and assemble them into songs and ideas for a new album, his first studio recording since '70's Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs. By the time he arrived in Miami to record 461 Ocean Boulevard, he had a portfolio of well-chosen covers and a handful of original compositions and a new minimalist approach, heavily influenced by J.J. Cale. On the album's release in July '74, opinion immediately divided into two opposing camps. To those whose idea of heavy rock heaven was a pummelling, 20 minute version of "Crossroads", his laidback mellowness was an ambition-free under-selling of his talent. More discerning fans who shared Clapton's admiration for the rootsier sounds of Cale, The Band, Leon Russell et al welcomed the humbler aesthetic and the tightly structured songs and hailed a career highlight. The follow up, '75's There's One In Every Crowd - the original title The World's Greatest Guitar Player (There's One In Every Crowd) was abbreviated by Robert Stigwood who thought the irony too subtle for Clapton's more lumpen fans - was cut from similar cloth and recorded in Jamaica, a choice of location which reflected the success of "I Shot The Sheriff" which had topped the Billboard singles chart. To promote the two studio albums, he toured with his American studio band, shows which were recorded for the '75 live album, E.C. Was Here. This six disc set presents those three original albums, all recorded within a fertile 15 month period, as an inter-linked trilogy, augmented by 29 bonus tracks, including studio out-takes, additional live material and a famous session with Freddie King, recorded in summer '74 for the bluesman's Burglar album. 5.1 surround sound and quadrophonic mixes of both studio releases complete the package. Marketed as a celebration of a "watershed era" that marked a "spectacular creative resurgence", the truth behind the record company hyperbole is somewhat more complex and interesting. Clapton's own description of his return is distinctly more modest, a sketchy, tentative process to find "a way to restore my playing capabilities in the company of proper musicians". But trying to break from his past and forge a new musical identity was a confusing and contradictory experience, as he was pushed and pulled in different directions by the expectations and demands placed upon him. Nowhere is this more evident than in the live material, when faced with an American stadium rock crowd yelling for his old warhorses, that's exactly what Clapton gave them. Of the 16 concert tracks, only three feature material from 461 Ocean Boulevard/There's One In Every Crowd. The rest constitutes a Cream/Blind Faith/Derek & The Dominos greatest hits set, which even when the old material is given a loping Tulsa groove cannot disguise a lack of confidence in his 'new' material. It didn't help that back on the road he was soon on autopilot once more, swapping heroin for brandy to self-medicate himself. At times the '74 tour found him so drunk he played while lying on the floor. A less severe judgement might hold that his new musical direction required smaller, more intimate venues than the same enormodomes he'd played and so hated with Blind Faith five years earlier. That he could still peel off technically brilliant extended guitar solos when called upon is evident from the Freddie King session and, in particular, a previously unreleased 22 minute jam on "Gambling Woman Blues". But almost 40 years on, it's the two studio solo albums that continue to fascinate most, as we hear him resolutely attempting to bury the 'old' Eric Clapton and trying on different musical personas to see what fits, from the reggae-lite of "Swing Low Sweet Chariot" and "Knockin' On Heaven's Door" to the J.J. Cale pastiche of "Steady Rollin' Man" and "Little Rachel" via the Harrison-cloned "High" and the lovely "Let It Grow", which bore the unintended influence of "Stairway To Heaven" by Led Zeppelin, a band he famously loathed. Paradoxically, out of this identity crisis, he fashioned some of the most coherent music of his career. Nigel Williamson

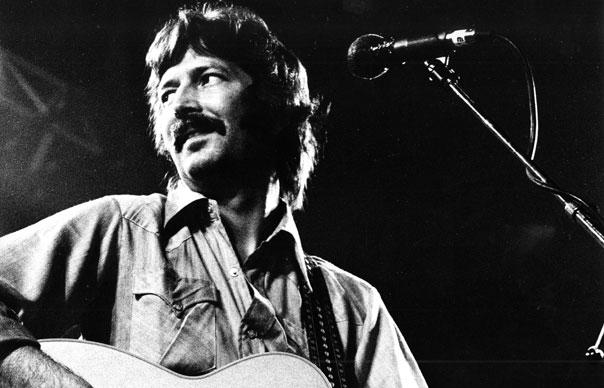

Six-disc set from the ‘identity crisis’ years – three albums, outtakes, lives and a session with Freddie King…

In his 2007 autobiography, Eric Clapton revealed the unconventional manner in which he prepared for his ’74 comeback after three years lost to heroin addiction. As part of his rehabilitation, he went to work on a Shropshire farm owned by Lord Harlech, the father of his then girlfriend Alice Ormsby-Gore, rising at dawn and “working like a maniac, baiing hay, chopping logs, sawing trees and mucking out the cows.” While regaining physical and mental fitness, the simplicities of farm life also gave Clapton untroubled space to collect his thoughts and assemble them into songs and ideas for a new album, his first studio recording since ’70’s Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs.

By the time he arrived in Miami to record 461 Ocean Boulevard, he had a portfolio of well-chosen covers and a handful of original compositions and a new minimalist approach, heavily influenced by J.J. Cale. On the album’s release in July ’74, opinion immediately divided into two opposing camps. To those whose idea of heavy rock heaven was a pummelling, 20 minute version of “Crossroads”, his laidback mellowness was an ambition-free under-selling of his talent. More discerning fans who shared Clapton’s admiration for the rootsier sounds of Cale, The Band, Leon Russell et al welcomed the humbler aesthetic and the tightly structured songs and hailed a career highlight.

The follow up, ’75’s There’s One In Every Crowd – the original title The World’s Greatest Guitar Player (There’s One In Every Crowd) was abbreviated by Robert Stigwood who thought the irony too subtle for Clapton’s more lumpen fans – was cut from similar cloth and recorded in Jamaica, a choice of location which reflected the success of “I Shot The Sheriff” which had topped the Billboard singles chart. To promote the two studio albums, he toured with his American studio band, shows which were recorded for the ’75 live album, E.C. Was Here.

This six disc set presents those three original albums, all recorded within a fertile 15 month period, as an inter-linked trilogy, augmented by 29 bonus tracks, including studio out-takes, additional live material and a famous session with Freddie King, recorded in summer ’74 for the bluesman’s Burglar album. 5.1 surround sound and quadrophonic mixes of both studio releases complete the package.

Marketed as a celebration of a “watershed era” that marked a “spectacular creative resurgence”, the truth behind the record company hyperbole is somewhat more complex and interesting. Clapton’s own description of his return is distinctly more modest, a sketchy, tentative process to find “a way to restore my playing capabilities in the company of proper musicians”. But trying to break from his past and forge a new musical identity was a confusing and contradictory experience, as he was pushed and pulled in different directions by the expectations and demands placed upon him.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the live material, when faced with an American stadium rock crowd yelling for his old warhorses, that’s exactly what Clapton gave them. Of the 16 concert tracks, only three feature material from 461 Ocean Boulevard/There’s One In Every Crowd. The rest constitutes a Cream/Blind Faith/Derek & The Dominos greatest hits set, which even when the old material is given a loping Tulsa groove cannot disguise a lack of confidence in his ‘new’ material. It didn’t help that back on the road he was soon on autopilot once more, swapping heroin for brandy to self-medicate himself. At times the ’74 tour found him so drunk he played while lying on the floor. A less severe judgement might hold that his new musical direction required smaller, more intimate venues than the same enormodomes he’d played and so hated with Blind Faith five years earlier.

That he could still peel off technically brilliant extended guitar solos when called upon is evident from the Freddie King session and, in particular, a previously unreleased 22 minute jam on “Gambling Woman Blues”. But almost 40 years on, it’s the two studio solo albums that continue to fascinate most, as we hear him resolutely attempting to bury the ‘old’ Eric Clapton and trying on different musical personas to see what fits, from the reggae-lite of “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” and “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” to the J.J. Cale pastiche of “Steady Rollin’ Man” and “Little Rachel” via the Harrison-cloned “High” and the lovely “Let It Grow”, which bore the unintended influence of “Stairway To Heaven” by Led Zeppelin, a band he famously loathed. Paradoxically, out of this identity crisis, he fashioned some of the most coherent music of his career.

Nigel Williamson