Unlike most people, or so it seemed from the film’s reviews, I emerged from a cinema showing Nick Broomfield’s Marianne & Leonard: Words Of Love earlier this year feeling rather less fond of Leonard Cohen than when I’d gone in. It was hard to ignore the fate of Marianne Ihlen’s son by a firs...

Unlike most people, or so it seemed from the film’s reviews, I emerged from a cinema showing Nick Broomfield’s Marianne & Leonard: Words Of Love earlier this year feeling rather less fond of Leonard Cohen than when I’d gone in. It was hard to ignore the fate of Marianne Ihlen’s son by a first husband, the novelist Axel Jensen, who had left her by the time she met Cohen on the Greek island of Hydra in 1960. Axel Jr, still just a baby when their affair began, was promptly sent back to Norway to be looked after by his grandmother. Later she brought him back to the community of artists on Hydra, and then took him with her when she pursued the Canadian poet to New York even as their relationship petered out towards the end of the decade. Axel Jr has spent much of his life as collateral damage, in and out of institutions, coping with psychiatric problems. Apparently Cohen often sent Marianne money to help them keep going until she met her second husband, an oil-rig engineer. As someone in the film says about children raised on Hydra, often it did not turn out well for them.

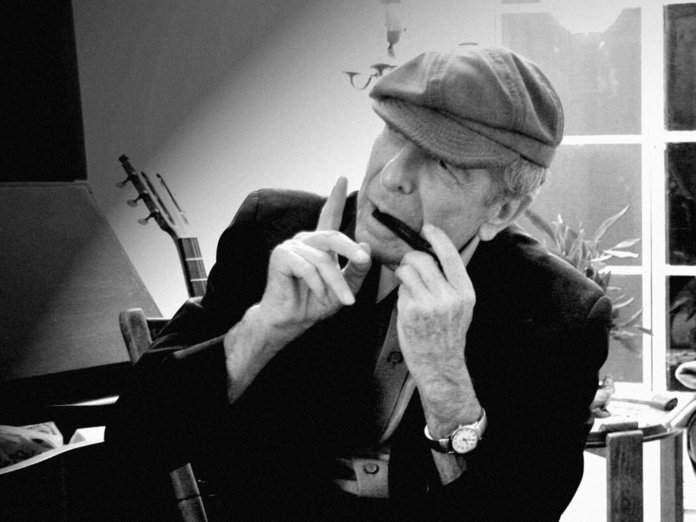

So the unexpected arrival of a new album under the name of Cohen, who died in November 2016 aged 82, might help to dispel the fumes lingering from Broomfield’s portrait of elegant but heedless self-indulgence. It restores the memory of an artist who, throughout his long career, made music that reconciled the gratified desires of the flesh with the austerity of a spiritual odyssey.

Cohen’s death occurred a couple of weeks after the release of his 14th studio album, You Want It Darker, which promptly flew up the charts around the world. Produced with scrupulous intelligence and the lightest of touches by his son Adam, it offered a fitting last word. On the epic title track, amid the sounds of funeral rites, he seemed to be saying goodbye to the world.

Thanks For The Dance is a postscript, pieced together by Adam Cohen from poems and lyrics recorded by his father at his home in Los Angeles and left behind after their work on You Want It Darker was done. Two tracks – “The Goal” and “Listen To The Hummingbird” – are based on poems initially recorded without music; the remaining seven were taped with skeletal accompaniment.

On hardly any of the nine tracks, amounting to just under half an hour of playing time, does Cohen actually sing. Exceptions are the title track, which just about manages to suggest a woozy melody, and the chorus of “Happens To The Heart”. Practically everything else is recited in that gently ruminative baritone, the voice of a man who’s seen too much but can’t stop looking.

As it turns out, this is absolutely fine. There may be nothing here that a Judy Collins would be racing to cover, no “So Long, Marianne” or “Bird On A Wire”, never mind a potential X Factor favourite like “Hallelujah”. But it reminds us that Cohen started life as a poet, winning prizes during his time as a student at McGill University, where he graduated in 1955, and publishing his first collection, Let Us Compare Mythologies, the following year. If this is also how he chose to finish, at least nobody read his poems as well as he did.

To flesh out the settings for these words, Adam Cohen called on a large company of collaborators, including some who had worked with his father, such as the virtuoso Spanish guitarist and laúd player Javier Más; the singers Jennifer Warnes and Sharon Robinson; Patrick Leonard, who created much of the music for Popular Problems, released in 2014; and Michael Chaves, who mixed and played on You Want It Darker. The tracks were worked on in Los Angeles, Montreal and Berlin, enabling members of André de Ridder’s s t a r g a z e orchestra and the Shaar Hashomayim male-voice choir to give their contributions. If this makes it seem like a large-scale project, that is not how the result sounds. Thanks For The Dance has the intimacy that characterised Songs Of Leonard Cohen and Songs From A Room half a century ago, only rarely making the listener conscious of the resources at Adam Cohen’s command.

“Happens To The Heart” is the opening track, the album’s longest and most fully realised piece, with one strong deadpan verse following another: “I was always working steady/But I never called it art/It was just some old convention/Like the horse before the cart/I had no trouble betting/On the Flood against the Ark/You see I knew about the ending/What happens to the heart.” Más weaves in and out, his nimble picking on the laúd (a lute-like instrument) making him sound like a Moorish Mark Knopfler, while Daniel Lanois selects precisely the right minimalist piano notes to underscore the song’s deliberate cadence. When the sound swells, it still seems weightless.

“It’s Torn” uses a subdued Morricone-like guitar twang for a lyric of unsettling sensuality: “You kick off your sandals and shake off your hair/It’s torn where you’re dancing, it’s torn everywhere/…It’s torn where there’s beauty, it’s torn where there’s death/It’s torn where there’s mercy but torn somewhat less/It’s torn in the highest from kingdom to crown/The messages fly but the network is down.” Even more powerful is “Puppets”, which opens with an evocation of fascism – “Germans puppets burned the Jews/Jewish puppets did not choose” – before bringing the picture closer to home and up to date: “Puppet presidents command/Puppet troops to burn the land…”

This is doggerel, but it packs a punch, particularly when counterpointed by a sombre choral arrangement and the sound of a distant tolling. “The Hills”, co-produced with Adam Cohen by Patrick Watson, is the most lavish piece, building at a stately pace to a dramatic climax, a little reminiscent of a vintage Roy Orbison 45. “The Nights Of Santiago” gets right down to business, with flamenco guitar and handclapping: “Behind a fine embroidery/Her nipples rose like bread/Then I took off my necktie/And she took off her dress/My belt and pistol set aside/We tore away the rest.” When Lennie says that nipples rise like bread, we must take his word for it.

Sometimes the ageing poet is so gloomy that you just have to laugh, in the fairly certain knowledge that he would have been chuckling along with you. “I sit in my chair, I look at the street/The neighbour returns my smile of defeat,” he says in “The Goal”, a 72-second haiku which amounts to a final reckoning but ends on a note of twisted optimism: “No-one to follow/And nothing to teach/Except that the goal/Falls short of the reach.” And the short overall playing time is immaterial: brevity can be the soul of poetry, too. There is no lack of substance here, brought to us with care by a devoted son.