After a Crazy Horse barn tour was cancelled owing to coronavirus touring restrictions, Neil Young devised other ways to perform live music for the masses. Choosing to keep on streaming in the free world, Young envisaged the Fireside Sessions: a “down-home production, a few songs, a little time tog...

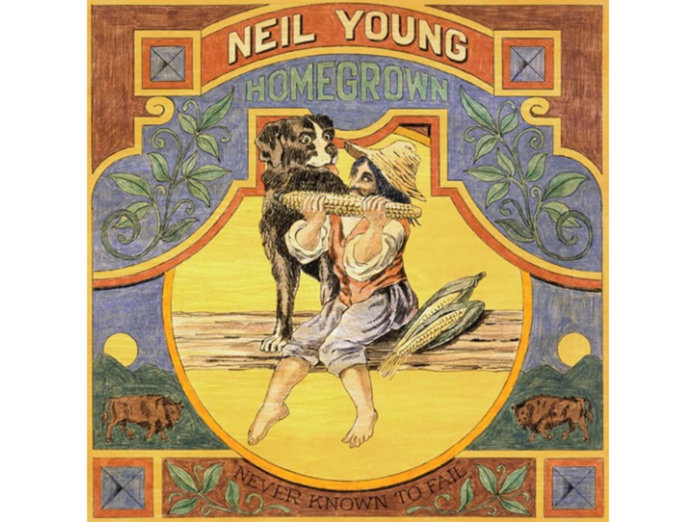

After a Crazy Horse barn tour was cancelled owing to coronavirus touring restrictions, Neil Young devised other ways to perform live music for the masses. Choosing to keep on streaming in the free world, Young envisaged the Fireside Sessions: a “down-home production, a few songs, a little time together” beamed live from his Colorado home. For the inaugural six-song acoustic set broadcast on March 19, Young pulled a couple of mouth-watering cuts from his sprawling catalogue. There was “Love/Art Blues”, debuted during CSNY’s 1974 tour, and the first solo outing for On The Beach’s “Vampire Blues” since 1974. Young closed the set with another deep cut: “Little Wing”, revived after an absence of over 40 years. A song about a benevolent bird that flies into town each summer, “Little Wing”’s inclusion felt especially timely. Although it appeared on 1980’s Hawks & Doves, its origins lie much further back, on Homegrown – one of Young’s legendary ‘lost’ albums, which finally arrives, 45 years late, in May.

Intended as a follow-up to On The Beach, Homegrown was pulled – apparently at the suggestion of The Band’s Rick Danko – in favour of a rehabilitated Tonight’s The Night. Young’s official reason for cancelling Homegrown was that its downbeat mood depressed him. Describing it now as “the sad side of a love affair”, at the time Young may have also felt uneasy about the number of songs about Carrie Snodgress, from whom he separated shortly before recording began. Five of Homegrown’s 12 songs later made it onto American Stars ’N Bars, Decade, Hawks & Doves and Ragged Glory. Among the other seven, several have only been played live a handful of times over the years, while three have never been heard until now.

Superficially, Homegrown resembles Hitchhiker – another ‘lost’ album from Young’s golden era that was finally released in 2017. But while Hitchhiker was a focused snapshot of Young’s creative process, recorded during one night in August 1976, Homegrown had more digressive beginnings. Sessions ran between June 1974 and January 1975 in Los Angeles, at Young’s Broken Arrow Ranch and even in England. The bulk of the work, though, took place at Nashville’s Quadrafonic Sound, where Young recorded Harvest along with producer Elliot Mazer. Reunited with Mazer and Harvest alumni Ben Keith on pedal steel and Tim Drummond on bass, Young also called on future International Harvester drummer Karl Himmel, Hawks/Band pianist Stan Szelest, Emmylou Harris, Levon Helm and Robbie Robertson.

More than just a trove of buried treasure from Young’s fecund ’70s – Homegrown is the missing chapter in his fabled Ditch Trilogy. Ben Keith’s exquisite pedal steel and Tim Drummond’s agile basslines provide a musical through-line; meanwhile, as Young picks through the debris of his relationship with Snodgress, Homegrown displays both the introspective qualities of On The Beach and the vérité nakedness of Tonight’s The Night.

Opener “Separate Ways” begins halfway through a chord, as if the band had started playing a split second before Mazer hit ‘record’. Sparsely arranged for a bare-bones ensemble, Young reflects on his split from Snodgress: “Though we go our separate ways/Lookin’ for better days/Sharin’ our little boy/Who grew from joy back then.” Keith’s pedal steel weeps sympathetically behind him as Levon Helm plays a slow, measured beat. The mood deepens with “Try”, a tribute to Snodgress’s mother, who committed suicide shortly after the couple separated. Here, Young incorporates some of her favourite expressions, including “Shit, Mary, I can’t dance”. Emmylou Harris harmonises on the chorus while Helm’s discreet fills and a lovely, rolling piano from the great Stan Szelest lift the final third of the song. The rainy days continue with the sorrowful “Mexico” – the first of three travelogues – where Young sits alone at the piano, asking, “Why is it so hard to hang on to your love?”

“Love Is A Rose” – familiar from Decade – opens with a supple bass run from Tim Drummond and a blast of Young’s harmonica before settling into the kind of palatable country-folk familiar from Harvest. Then it’s into “Homegrown” itself. Essentially a goofy jam about the pleasures of the herb, the version here is breezier and funkier than the Crazy Horse re-recording on American Stars ’N Bars. It’s welcome light relief before Young drifts back into his cursed fog. On the unreleased spoken-word piece “Florida”, he relates a macabre yarn about a glider crashing into a 15-storey building in the city centre. On this, Young is accompanied by what could either be a saw, a detuned violin or perhaps someone running a wet finger around the rim of a glass – or, more likely, all three.

After the strangeness of “Florida”, “Kansas” is a more conventional acoustic piece. The narrator wakes up to find a companion lying next to him in bed – “Although I’m not so sure if I even know your name.” With its world-weary delivery, “Kansas” resembles one of the more downcast moments from On The Beach, the harmonica motif seeming to reference “Ambulance Blues”. Thematically, it is another meditation on the hollowness of stardom – this transient romantic assignation takes place “In my bungalow with stucco/That the glory and success bought.” With the album’s temperament growing unstable, Young withdraws into “We Don’t Smoke It Anymore” – a strung-out blues vamp that wouldn’t sound out of place on Tonight’s The Night.

Sometime in September 1974, shortly before CSNY played Wembley Stadium, Young and Robbie Robertson recorded a song called “White Line”. You’ll know the electrified version from Ragged Glory, of course; but here, in a simple acoustic arrangement, it casts a note of wary optimism: “I’ve been down but I’m coming back up again.” The guitar interplay between Young and Robertson is warm, complementary – you might wish they’d collaborated musically more often. Meanwhile, whatever positive emotions Young had experienced on “White Line” have evaporated by the time the churning riffs of “Vacancy” start up. This is Young at his most fractious. “I look in your eyes and I don’t know what’s there,” he sings in a sarcastic jeer. “You poison me with that long vacant stare.” Is he addressing Snodgress directly? Or perhaps he’s expressing a broader disdain for the industry sharks and hangers-on around him?

The album winds down with two more acoustic songs: “Little Wing” and “Star Of Bethlehem”. If you squint hard enough, it’s possible to read the former as an allegory about Snodgress – “Little Wing, don’t fly away” – but “Star Of Bethlehem” rages with acrimony and betrayal. A crepuscular ballad, graced with elegant harmonies from Harris, it finds Young at his most merciless: “All your dreams and your lovers won’t protect you/They’re only passing through you in the end/They’ll leave you stripped of all that they can get to/And wait for you to come back again.” As with much of Homegrown, a heaviness crashes through the mellow musical vibes.

Had Homegrown been released in June 1975, as intended, would Young’s career be any different? Does this previously missing instalment of the Ditch Trilogy (now Quartet?) alter our perceptions of the releases around it? If Time Fades Away, On The Beach and Tonight’s The Night address the tragedies of Young’s recent past and his disillusionment with the limousine lifestyle Harvest bought him, Homegrown telescopes in on troubles at home – making it the most human of this run of albums. Young’s writing is unashamedly autobiographical in ways it has seldom been since (other unreleased songs from this period like “Frozen Man”, “Homefires” and “Love/Art Blues” further illuminate Young’s inner character). He is bereft, injured, cold – but he also experiences a certain karmic resignation. As he sings on “Separate Ways”: “Me for me, you for you/Happiness is never through/It’s only a change of plan/And that is nothing new.” There will always be heartbreak and loss. It’s the way things are and the way they will always be. It’s Young’s Chinatown moment.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner