An accidental visionary and "star in his own world"... the strange tale of a cult punk hero... “There’s no one faking it less than Johnny Moped,” says Captain Sensible, introducing his son Fred Burns’ affectionate portrait of Croydon’s most unlikely punk rock demiurge. Except, that is, when it comes to his tattoos. Within days of seeing the photo on the sleeve of his band’s perverse 1978 album Cycledelic, the local Hells Angels chapter sent an emissary to the once and future Paul Halford, insisting that the punk rock oddity cover up his unauthorised ‘Hells Angels, Croydon’ tattoo or lose his arm. Thus, he and his teenage girlfriend were compelled to spend their last £5 to get a local tattooist to crudely superimpose a dismal green parrot over the offending inkwork. A colourful portrait which masks something darker, Basically, Johnny Moped bristles with such weird and pathetic tales. The director first met his leading man in the pub ahead of a family trip to a Crystal Palace game and, enraptured by the bizarre lore that surrounded the singer, has woven together some excellent contemporary footage and contributions from Johnny Moped, the band and their biggest fans (“It was like The Beatles,” mumbles Shane McGowan) into a portrait of an accidental visionary amid the poseurs of punk. Describing himself to one band-mate as having “an 82% disability”, Johnny Moped’s music – an amalgam of free festival boogie and grunting Stooges thud – might never have escaped from Croydon had it not been for the sudden industry thaw occasioned by the Sex Pistols. Basically, Johnny Moped tracks the South Londoners from a world of sparsely-attended back-garden gigs to an unlikely sort of minor celebrity, with extraordinary debut single “No One” only marginally upstaged by the B-side “Incendiary Device” (“Stick in in her lughole, stick it in her other parts”). Things would get odder still with the stoned innocence of follow-up “Darling, Let’s Have Another Baby” and then Cycledelic – by which time the recalcitrant singer was being kidnapped from outside his workplace in order to record his vocals (“we took his trousers away as an emergency measure” recalls drummer Dave Berk). Although Johnny Moped left only a small mark on pop, Burns is spoiled for choice when it comes to subplots; the Erik Satie pretensions, alcoholism and suicide of bassist Fred Berk; the impact Johnny Moped had on refreshingly game interviewee Chrissie Hynde, and the curious Romeo And Juliet story of the singer and his on-off girlfriend and now wife Brenda – 20 years his senior, but under the protective eye of a fearsome mother. Burns’ queasiness at addressing Johnny Moped’s marginal state – beyond the occasional lingering shot of a can of White Star cider – leaves some nagging unanswered questions, but despite those unnerving Elvis In Jarrow parallels, Basically, Johnny Moped celebrates an improbable triumph, rather than a Devil And Daniel Johnson-style tragedy. “He was a star, just not in quite the same world that everybody else existed in,” says Chiswick records boss Roger Armstrong diplomatically as he ponders his former protege. Strange, but true. Jim Wirth

An accidental visionary and “star in his own world”… the strange tale of a cult punk hero…

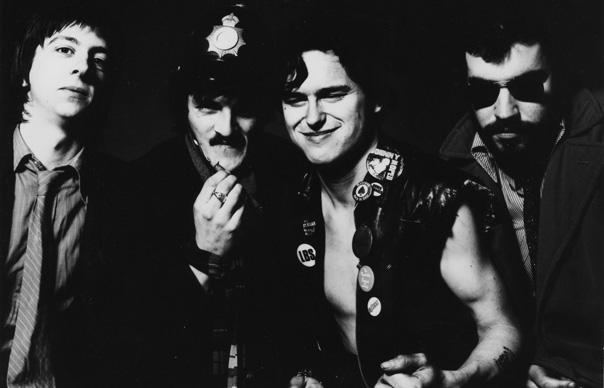

“There’s no one faking it less than Johnny Moped,” says Captain Sensible, introducing his son Fred Burns’ affectionate portrait of Croydon’s most unlikely punk rock demiurge. Except, that is, when it comes to his tattoos. Within days of seeing the photo on the sleeve of his band’s perverse 1978 album Cycledelic, the local Hells Angels chapter sent an emissary to the once and future Paul Halford, insisting that the punk rock oddity cover up his unauthorised ‘Hells Angels, Croydon’ tattoo or lose his arm. Thus, he and his teenage girlfriend were compelled to spend their last £5 to get a local tattooist to crudely superimpose a dismal green parrot over the offending inkwork.

A colourful portrait which masks something darker, Basically, Johnny Moped bristles with such weird and pathetic tales. The director first met his leading man in the pub ahead of a family trip to a Crystal Palace game and, enraptured by the bizarre lore that surrounded the singer, has woven together some excellent contemporary footage and contributions from Johnny Moped, the band and their biggest fans (“It was like The Beatles,” mumbles Shane McGowan) into a portrait of an accidental visionary amid the poseurs of punk.

Describing himself to one band-mate as having “an 82% disability”, Johnny Moped’s music – an amalgam of free festival boogie and grunting Stooges thud – might never have escaped from Croydon had it not been for the sudden industry thaw occasioned by the Sex Pistols. Basically, Johnny Moped tracks the South Londoners from a world of sparsely-attended back-garden gigs to an unlikely sort of minor celebrity, with extraordinary debut single “No One” only marginally upstaged by the B-side “Incendiary Device” (“Stick in in her lughole, stick it in her other parts”). Things would get odder still with the stoned innocence of follow-up “Darling, Let’s Have Another Baby” and then Cycledelic – by which time the recalcitrant singer was being kidnapped from outside his workplace in order to record his vocals (“we took his trousers away as an emergency measure” recalls drummer Dave Berk).

Although Johnny Moped left only a small mark on pop, Burns is spoiled for choice when it comes to subplots; the Erik Satie pretensions, alcoholism and suicide of bassist Fred Berk; the impact Johnny Moped had on refreshingly game interviewee Chrissie Hynde, and the curious Romeo And Juliet story of the singer and his on-off girlfriend and now wife Brenda – 20 years his senior, but under the protective eye of a fearsome mother. Burns’ queasiness at addressing Johnny Moped’s marginal state – beyond the occasional lingering shot of a can of White Star cider – leaves some nagging unanswered questions, but despite those unnerving Elvis In Jarrow parallels, Basically, Johnny Moped celebrates an improbable triumph, rather than a Devil And Daniel Johnson-style tragedy.

“He was a star, just not in quite the same world that everybody else existed in,” says Chiswick records boss Roger Armstrong diplomatically as he ponders his former protege. Strange, but true.

Jim Wirth