Young Shakespeare, the latest in Young’s ongoing Performance Series (this is vol 3.5 for those crazy enough to keep track), captures the songwriter at the cusp of solo superstardom. He was still best known as the Y in CSNY but he’d packed several lifetimes’ worth of activity into a very brief ...

Young Shakespeare, the latest in Young’s ongoing Performance Series (this is vol 3.5 for those crazy enough to keep track), captures the songwriter at the cusp of solo superstardom. He was still best known as the Y in CSNY but he’d packed several lifetimes’ worth of activity into a very brief span of time: from the break-ups and make-ups of Buffalo Springfield to the dangerously unstable Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, from the lukewarm reception of his debut 1968 solo LP to the formation of Crazy Horse. Now, as he walked on stage at Stratford Connecticut’s Shakespeare Theatre in January of 1971, he was alone again, naturally, and rapidly emerging as a force to be reckoned with.

Both Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere (his first collab with Crazy Horse) and the then-freshly released After The Gold Rush had been powerful statements of intent, unearthing a glittering vein of sonic possibilities that Young continues to mine to this day. Neil’s confidence as a performer was growing with leaps and bounds too, his distinctive, percussive acoustic guitar technique crystallising and his high, lonesome vocals becoming more bewitching.

This era is well represented in Young’s always expanding archival universe; indeed, Live At Massey Hall 1971 (released as Performance Series 3.0 in 2007) was recorded just a few days prior to the Shakespeare Theatre show, and Live At The Cellar Door (released as Performance Series 2.5 in 2013) comprises solo performances from December 1970. (There’s even more to come: Neil recently announced a Bootleg Series that will include three more late ’70/early ’71 solo shows.) With a setlist and overall mood that doesn’t deviate wildly from Massey Hall 1971, some fans might find reason to complain about Young Shakespeare. Maybe one can have too much of a good thing? But in a world where listeners can immerse themselves in every last note of Dylan and the Hawks’ 1966 tour or the Grateful Dead on their Europe ’72 trek, more examples of Neil Young at this early peak are welcome.

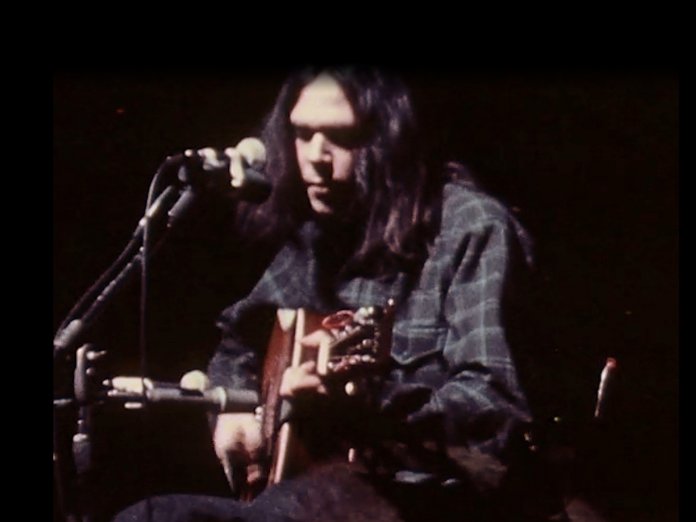

Young Shakespeare is differentiated by its visual accompaniment – a murky but absorbing 16mm document of the show made by Dutch filmmaker Wim van der Linden (and subsequently edited by Young’s directorial alter ego Bernard Shakey). Flannel-clad Neil is a shadowy but friendly presence as he moves from guitar to piano, at times gently ribbing his audience with a wry joke, at others earnestly seeking a connection. At this point, Young’s stage presence is the perfect mix of seductive mystique and aw-shucks bonhomie.

The performance itself? Flawless. Even at this early stage, Neil had an impressive stash of songs to draw from, and he dispatches tunes from Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, Déjà Vu and After The Gold Rush with focus and precision. These may be relatively new compositions but they already sound like sturdy classics on stage, from the wistful opener, “Tell Me Why”, to the moody acoustic remakes of “Cowgirl In The Sand” and “Down By The River”. Instead of coasting on past successes, however, Young takes the opportunity to debut several new numbers destined to become signature concert favourites. “Old Man”, inspired by the foreman on Neil’s northern California ranch, is close to fully formed; the songwriter would record its definitive Harvest version in Nashville just a few weeks later. Young prefaces “The Needle And The Damage Done” with a ramble that references the recent heroin-related deaths of Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix but it’s likely he had another musician in mind: guitarist Danny Whitten, whose drug habits had caused Neil’s break-up of Crazy Horse in 1970. Whitten passed away in 1972 while trying to kick heroin.

Equally heavy is “Ohio”, a song less than a year old, but a fresh wound for the counterculture. Written and recorded in the immediate wake of the Kent State massacre of May 1970, the CSNY single is militant and aggressive, with piercing guitars and urgent vocals. In Stratford, the acoustic “Ohio” is a more mournful thing, a personal lament, the lines that cut the deepest here: “What if you knew her/And found her dead on the ground?” However, Young is enough of a showman to follow up this dark cloud with the featherweight hoedown “Dance Dance Dance”, which serves to lighten the mood considerably.

As on Massey Hall 1971, Young Shakespeare’s most interesting highlight is the “A Man Needs A Maid”/“Heart Of Gold” medley, performed on piano and introduced by Young sheepishly as “my most elaborate accomplishment”. But elaborate it is. “Maid” is a dramatic performance, even when stripped of its bombastic Jack Nitzsche arrangement, Young’s vocal rising over crashing minor chords. “Heart Of Gold”, by contrast, is given an intimate, hopeful reading. In just about a year’s time, the song (in a radically altered form) would take Neil to the top of the charts. But there’s an even more enticing hint of things to come; during the medley’s elegant instrumental preamble, Young plays the unmistakable melody of “Borrowed Tune”, a song that wouldn’t appear on record until 1975. It’s brief moments like these that remind us of why releases such as Young Shakespeare are essential to our appreciation of the songwriter’s long career. They give us a valuable, if slightly blurry, freeze-frame of an artist who is always in motion – here one minute, gone the next.