“Bought fertiliser and brake fluid/Who in the hell am I supposed to trust?” John Murry’s new album opens with a song about a man building a bomb that somehow introduces Oscar Wilde into a narrative about American unrest. Domestic terrorism, the Oklahoma bombing, gas chambers, low-flying police...

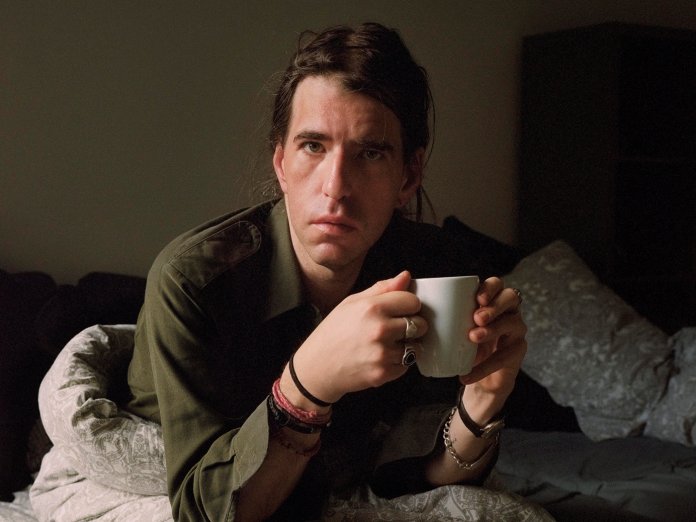

“Bought fertiliser and brake fluid/Who in the hell am I supposed to trust?” John Murry’s new album opens with a song about a man building a bomb that somehow introduces Oscar Wilde into a narrative about American unrest. Domestic terrorism, the Oklahoma bombing, gas chambers, low-flying police helicopters, natty Oscar playing bridge. Longstanding fans will take these uneasy juxtapositions in their stride. Nearly everything Murry’s released to date has sounded like a dispatch from one war zone or another – both his previous solo albums tackle the issue of trauma.

There was more to 2013’s The Graceless Age than a plainly autobiographical song about flatlining after a heroin overdose. But the album was eventually dominated by the nine pain-wracked minutes of Little Coloured Balloons. It’s still the song everyone wants to hear him play when they see him live, a man who came back from the dead singing about his own resurrection.

A Short History Of Decay (2017) was written in the aftermath of a nasty divorce, Murry simultaneously rocked by the death of former American Music Club drummer Tim Mooney, who produced and, over the four years of its making, helped shape the songs on The Graceless Age. Mooney gave the album a dense, textured sound: layers of keyboards, strings, crackling radio broadcasts; synthesisers and sundry electronics. Cowboy Junkies’ Michael Timmins produced the follow-up, the whole thing taped and mixed in just five days. It sounded like it had been recorded in a lost, lonely place. A holding cell or isolation ward, perhaps.

At first listen, The Stars Are God’s Bullet Holes comes from a similarly dour location at the end of the line, ill-lit and funky. Its mood is generally heavy but a frailty prevails, something vaguely tranquilised about a lot of the record. There seems initially to be not much body at all to bits of it. At one point or another, most of the album sounds in fact like it should be on life-support. Even the handclaps sound worn out. The songs mostly are reduced to sinew and gristle, as if the meat has been chewed off them by passing coyotes.

Play it again, however, and it’s neither listless nor inert. Murry and producer John Parish know a thing or two about creating compelling atmospheres out of meagre resources. The album is built from vocal and instrumental tics and spasms. Guitars that crackle like burning wallpaper. Glitchy electronics that course through the tracks like syntax errors in a

computer code, Nadine Khouri’s timelapse harmonies. Scraps of pedal steel, piano, cello.

Oscar Wilde (Came Here To Make Fun Of You) casts individual turmoil alongside wider public derangement. Ones + Zeros starts as a frayed ballad about dashed hopes that decides it’s time to reject oppression. “Spit on your hands, raise the black flag/ Cut each throat, drown the old hag…” An unexpected version of Duran Duran’s Ordinary World that turns it into an insidious stalking blues with pustulant guitar also pits singular distress against a broader disintegration.

Mostly, though, Murry is concerned with personal emotional plight, the scorched earth of his own life. Perfume & Decay is a song about an imploding relationship that sounds like a drugged message on an answerphone. The title track essays similar territory, carried by the fuzz-box malignancy of Murry’s writhing electric guitar. Murry carries grudges like an old-school Mafia boss with a hundred recipes for dishes best served cold. Revenge runs through these songs like a virus, infecting track after unvaccinated track.

“God may forgive them for what I can’t forget”, Murry sings grimly on Time & A Rifle, over a messy, slithering guitar riff. The otherwise beautiful Di Kreutser Sonata turns a fierce gaze on his adoptive family (“They didn’t adopt me, they bought me,” Murry recently wrote on his website), the track ending with whistling and a dreamy instrumental coda that sounds like the closing theme to a film that’s left everyone dead in a Mexican desert. I Refuse To Believe (You Could Love Me) is a desiccated glam stomp, Murry baffled by his romantic predicament over a Moe Tucker backbeat.

1(1)1 is two minutes of ugly noise as superfluous as a ‘hidden’ bonus track, possibly called You Don’t Miss Me, a thrashing thing. The album as advertised properly ends, however, with the reptilian loop of Yer Little Black Book, Murry sitting in his car, singing along to a radio playing Joy Division’s She’s Lost Control, thinking about his own worthlessness as the last light fades on another day in paradise.