Over the past few decades, Soul Jazz have made a name for themselves with stylish, smartly conceptualised comps. Their curatorial touch is sure but lightly applied, and if they sometimes skirt predictability, there’s something to be said for the reliability of their approach, particularly when tak...

Over the past few decades, Soul Jazz have made a name for themselves with stylish, smartly conceptualised comps. Their curatorial touch is sure but lightly applied, and if they sometimes skirt predictability, there’s something to be said for the reliability of their approach, particularly when taking on a catalogue as deep as the productions made at Clement Dodd’s Studio One, the ‘Motown of Jamaica’. A legendary place, with Dodd a gifted producer, some of reggae’s greatest passed through – Bob Marley, Burning Spear, Bunny Wailer and Johnny Nash all cut sides there, often backed by house band the Skatalites; arranger Jackie Mittoo finetuned his craft at the studio, too.

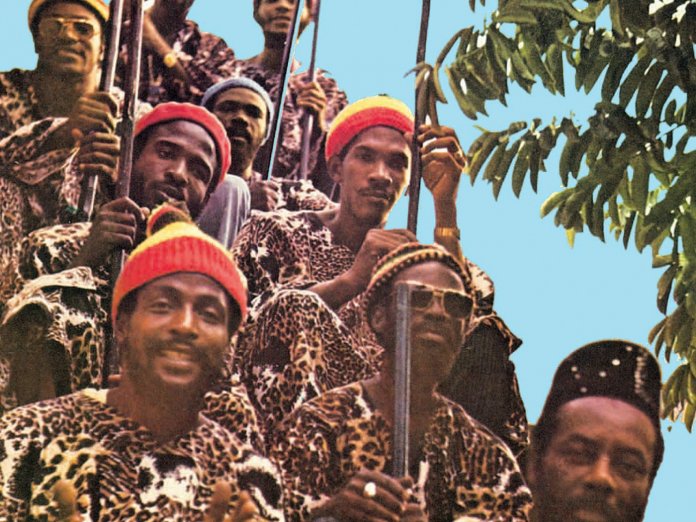

Fire Over Babylon is particularly potent, though, for its focus, pulling together a selection of Studio One sides lit by the devotional spirit of Rastafarianism. A religion steeped in defiance of ongoing colonial invasion, Rastafarianism cohered as a belief system in the 1930s, with preachers calling for a return of all black people to Africa, following the appearance of their new god. Rastafarianism’s history is a complex one, a sect in perpetual battle with hegemonic institutional forces (the police, the government), defiantly anti-capitalist, and imbued with a deep sense of righteousness, ‘rebel spirit’, and a relentless drive towards black self-determination.

Dodd never clearly articulated his faith to the public, but he ran deep with Rastafarian artistic communities. He’d take members of the Skatalites to drummer Count Ossie’s ‘reasoning and jam sessions’ in Jamaica’s Blue Mountains. Ossie was central to the development and dissemination of nyabinghi, a compelling rhythmic base to those reasoning sessions. At its most furious and expansive, Ossie’s music was properly psychedelic, as form-disruptive and mantric as free jazz: Soul Jazz head Stuart Baker describes Ossie’s work with Cedric “Im” Brooks and the Mystic Revelation Of Rastafari, as a “supergroup the equivalent of Sun Ra and John Coltrane in jazz”.

Ossie’s contribution to Fire Over Babylon, ecorded in collaboration with Brooks, feels like the centrepiece of the collection, the magnetic attractor around which all the other material gathers. On Give Me Back Me Language And Me Culture, the flipside of a 1971 single that originally appeared on producer and label owner Junior Lincoln’s Banana imprint, Ossie and Brooks tie everything together in a spectacular production: the bubbling brook of hand-pulsing rhythms draw from nyabinghi traditions; the brass arrangement calls back to mento; the bass is a slow, sly depth charge; the vocal chorus is gently insistent, an imploring chant.

Just as often, though, the heaviness of the songs’ content is often belied by the fleet-footedness of the production – Devon Russell’s Jah Jah Fire, for example, is breezy, aerated, its rustling, buzzing organ the melodic sugarcoating on Russell’s devotional plaint. By contrast, The Gladiators’ Sonia is starchy and stripped back, its rhythm carved from a granite block of texture, a minimalist masterpiece of interlocking parts. There’s a fierceness to the discipline here that can gift even the lightest of production touches with the heaviest gestural implications: the playing is tight, in the pocket, the better to build a solid foundation for the vocalists’ to-and-fro chants and soul-spun melancholy.

That discipline, something that’s always felt core to Clement Dodd’s productions with Studio One, isn’t stentorian, though. There’s great playfulness and pleasure at the heart of Fire Over Babylon: from the way the trumpet skates and glides over the lithe rhythms and dubbed-out rimshots of Judah Eskender Tafari, or the hissing hi-hats and wandering bass that grounds The Prospectors’ Glory For I, there’s space here for joy and celebration, too. Wailing Souls’ Rock But Don’t Fall, a lovely, chimeric thing that rides in on chiming piano chords and a muted guitar riff, captures the spirit here tidily: spiritual but open, light and loving but with depth of conviction.

If there’s any risk here, it’s that Fire Over Babylon doesn’t allow for the extension that can make Rastafarian roots music so intoxicating. Some of the most powerful material in this realm was recorded elsewhere, like Dadawah’s Peace And Love: Wadadasow, and the epochal sets Ossie and Brooks essayed with Mystic Revelation Of Rastafari, titles like Grounation, Tales Of Mozambique and One Truth. That’s maybe a little unfair to Soul Jazz’s focus on the Studio One archives, and they’ve certainly done an excellent job with Fire Over Babylon. Think of it as just one of many angles you could take on this eternally nourishing music, and you won’t walk wrong.