When Taste broke up in the autumn of 1970, Rory Gallagher went through the mixed emotions that follow any divorce. There was pride: their final festival appearance at the alongside and had been spectacular and their last studio album, 1970’s On The Boards, had fused Gallagher’s driving blues-roc...

When Taste broke up in the autumn of 1970, Rory Gallagher went through the mixed emotions that follow any divorce. There was pride: their final festival appearance at the alongside and had been spectacular and their last studio album, 1970’s On The Boards, had fused Gallagher’s driving blues-rock with jazzier, more experimental influences and taken the band into the UK albums chart for the first time.

Yet there was frustration and anger, too. There was enmity with Taste’s manager Eddie Kennedy, who had signed a recording deal with Polydor that gave him ownership of the band, with Gallagher and the other two members of Taste individually under contract to him as employees.

There were also tensions within the trio, as drummer John Wilson and bassist Richard McCracken increasingly came to resent Gallagher taking the limelight as guitarist, singer and songwriter. After Taste had played their final gig, Wilson savaged Gallagher in the music press, claiming the band had broken up owing to the guitarist’s greed and arrogance.

Neither were traits that anybody who knew Gallagher remotely recognised and it was typical of his generosity and modesty that he refused to respond. He preferred to look forward rather than back and Taste had turned so sour that he refused to play the band’s material in his live sets for the rest of his life.

Keeping his eyes on the horizon meant going solo and a new deal with Polydor, negotiated with the assistance of Led Zep manager Peter Grant, who stormed into the office of Polydor’s MD, ripped up the offered contract and told him, “Give Rory a decent fucking deal.” The outcome was a six-album deal on substantially more generous terms.

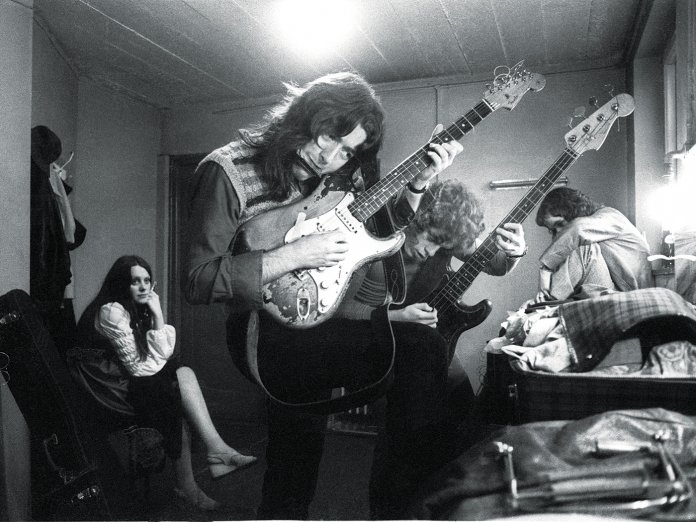

Gallagher wanted a fresh approach but was still wedded to the idea of a power trio, and a new rhythm section was required to back him. According to one story, Robert Stigwood tried to persuade him to play with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker in a putative Cream Mark II. Gallagher rejected the idea of being shoehorned into Eric Clapton’s fringed boots, but he did try working with Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell, both of whom were at a post-Hendrix loose end. In the event he found what he was seeking closer to home in drummer Wilgar Campbell and bassist Gerry McAvoy from Deep Joy, an Irish band that had supported Taste at the Marquee.

By the time Gallagher’s eponymous solo debut finally appeared in May 1971, it was almost 18 months since Taste’s final studio album and the songs were tumbling out of him. It’s not hard to see references to the break-up of Taste in the lyrics of songs such as I Fall Apart and For The Last Time. But it’s the breadth and nuance of the material that is most striking. Laundromat boasts a classic Gallagher blues-rock riff, as does Sinner Boy with its stinging slide guitar. But thereafter things get gentler and more introspective, in the manner of the more acoustic-tinged material on Led Zeppelin III.

Heavily influenced by his admiration for Davy Graham, Bert Jansch and John Renbourn, Just The Smile would not have been out of place on a Pentangle album. Can’t Believe It’s True has a West Coast vibe, a Jefferson Airplane jam maybe. On the acoustic down-home blues of Wave Myself Goodbye and I’m Not Surprised – inspired by Gallagher’s discovery of the 1930s recordings of Scrapper Blackwell and Blind Boy Fuller – the rhythm section is banished and replaced by the boogie-woogie piano of Atomic Rooster’s Vincent Crane. It’s You is pure country and oozes with Gallagher’s love of Hank Williams.

This anniversary edition expands the album’s 10 original songs somewhat gratuitously to more than 50 tracks. ’ Gypsy Woman and Otis Rush’s It Takes Time are ferocious excursions into electric Chicago blues. The gentle folk-rocker At The Bottom heard in four almost identical takes and on which Gallagher blows some lovely harmonica, eventually appeared on the 1975 album Against The Grain. For the rest it’s mostly alternate takes of songs on the album, several of them breaking down and few, if any, departing radically from the versions that made the cut.

The final disc of radio sessions offers further iterations of six of the songs on the 1971 album plus a preview of In Your Town, a stomping slide-guitar showcase that would appear six months later on Gallagher’s second solo set, Deuce.

By coincidence Gallagher and Clapton both released their self-titled solo debuts within a few months of each other – and in terms of blues-rock guitar-slingers seeking to expand their signature sound, Gallagher’s effort at this distance stands up as more coherent, consistent and focused. More than a quarter century on from his death, he’s missed more than ever.