Michael Chapman quit music just the once. Returning from America in 1971, where he’d supported Cannonball Adderley, been threatened by Black Panthers and very much failed to be paid, he vowed to leave it all behind. His new life lasted about three days.

“A promoter friend of mine in Holland called,” the songwriter recalled in 2016. “I told him I’d retired and he said, ‘Oh, you don’t want to tour with The Everly Brothers, then…’

I said, ‘When does it start?’ ‘Tomorrow.’ Since then, no, I’ve not wanted to give it up. It’s not plain sailing, you know, it’s not a regular job. But there’s a saying around here, ‘If you can’t shit, get off the pot.’”

For the next 50 years, Chapman resolutely stayed on that pot, releasing records and touring at a rate that would exhaust most musicians. When he passed away last month at the age of 80, at the rustic house set between the north Pennines and Hadrian’s Wall where he’d lived since failing to quit the business a half-century before, he was revered – a no-nonsense legend, always authentic, the fully qualified survivor that the title of his second album had promised. He had gigs booked for 2022 and was busy practising.

“Very few of us make any money,” Chapman told Uncut. “That’s what we do it for, the free T-shirts and stories. But you’re always welcome at a dinner party.”

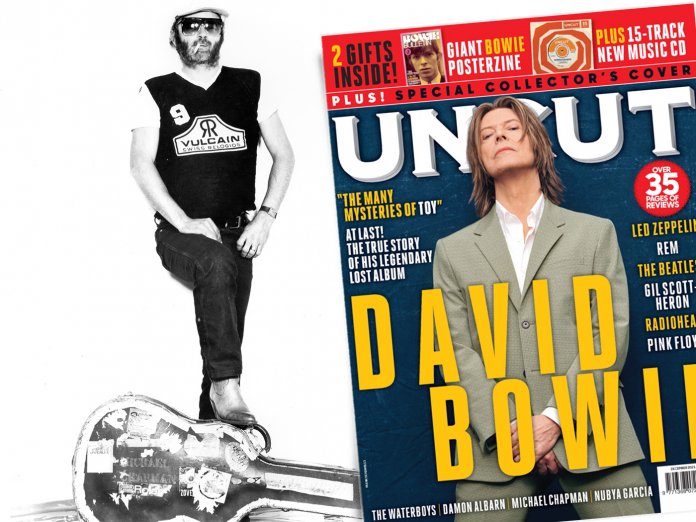

The occasion for our trip north was the release of 50, Chapman’s penultimate solo album and his first proper ‘American’ album, on North Carolina’s Paradise Of Bachelors label. In that wild landscape, Uncut found an artist excited about music, the album and the interview, keen to share his stories, his guitars and his impressive wine collection. The trucker cap stayed on everywhere except the house, where Chapman fixed visitors with a stare through his aviator glasses, warmly teasing them in his gruff, Yorkshire tones, while genuinely interested in learning their thoughts on life and music. He wasn’t always laughing, but he was, it seems, always joking.

The house was a marvel, a step back in time, heated only by an Aga and a wood fire – the kind of place where, in Chapman’s case anyway, you keep your cowboy boots on in the lounge. The walls were adorned with artful pictures of Chapman and his wife Andru, LP sleeves, posters and, of course, a huge record collection, which the guitarist would plumb throughout the evening. A Grant Green record was replaced by an electric Django Reinhardt rarity, in turn followed by a CD-R of Daniel Land live at London’s Lexington. And so on, long into the night.