With an oeuvre devoted to the poison, perversity and paranoia of the 20th century and a passion for telling tales of ambition, fame and oblivion, you couldn’t imagine a director better suited to a Velvet Underground documentary than Todd Haynes. But though you might have hoped for some occult, o...

With an oeuvre devoted to the poison, perversity and paranoia of the 20th century and a passion for telling tales of ambition, fame and oblivion, you couldn’t imagine a director better suited to a Velvet Underground documentary than Todd Haynes. But though you might have hoped for some occult, oneiric version of the story told via fabulist casting, phantasmagoric CGI and a little puppetry, The Velvet Underground: A Documentary Film by Todd Haynes is a story as straight as its title.

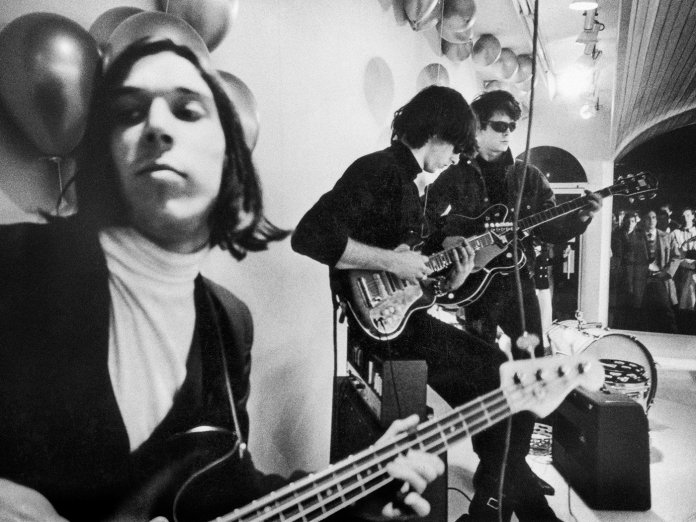

Understanding the challenge of making a movie about a band three of whose members are dead, and who left almost no live footage, Haynes has cast the net far and wide across the archives of the world for B-roll. Indeed the film is dedicated to the memory of Jonas Mekas, founder of New York’s Film-Maker’s Cooperative, who died during production and at whose early-’60s screenings Warhol began to cast his Factory superstars. The result is a loving homage to the Lower East Side and a split-screen secret history of 1960s American underground cinema from Stan Brakhage, Marie Menken and Maya Deren, to Jack Smith and Kenneth Anger.

And – overwhelmingly of course – Andy Warhol. The film opens in a squall of Cale viola, a frenzied, channel-hopping montage of 1963, and then a young Lou gazing dreamily into Andy’s impassive lens, as though seeing clearly through the storm, steadfastly focused on… what? Riches and fame (high school bandmates and his sister recall a steely determination to become “a famous rock star”)? Literary immortality as predicted by college mentor Delmore Schwartz? Or simply his own chemical and sexual oblivion (he seemed compelled to shock his school and college friends with squalid adventures in search of degradation)?

The first scene features a spiffy Cale appearing on I’ve Got A Secret, the early-’60s CBS panel show, as a token avant-garde wacko, fresh from an 18-hour performance of Satie. But if Haynes’ earlier investigations into rock history were propelled by genuine mystery and loss – who killed Karen Carpenter? What happened to David Bowie in the ’80s? Who on earth is Bob Dylan? – The Velvet Underground can feel a little like a diligent, almost academic tribute to the cross-cultural crosstown traffic of mid-’60s NYC, rather than an urgent enquiry into an enduring musical miracle.

Certainly Uncut-reading VU-heads will be abundantly familiar with the story of Lou as Pickwick’s jobbing songwriter meeting the conservatoire rebel Cale and together discovering the negative zone where Bo Diddley backs La Monte Young and garage-band primitivism meets transcendent drone. Mary Woronov and Amy Taubin are on hand to recall the early days of the Factory (there’s some marvellous footage of a wacked-out superstar tarot reading) and Warhol’s ambition to make the Velvets, now incorporating the lunar glamour of Nico, the house band at “the biggest discotheque in the world”. And you’ll know of the dismal sales, disastrous tours and bitter feuds that followed four of the greatest albums ever made.

There’s little fresh light cast on the band dynamics. Lou is described as behaving like a nihilistic three-year-old throughout (who Nico and Andy were nevertheless besotted with), and though Mo Tucker admits the band lost something without Cale, she has little perspective on the way she and Sterling Morrison meekly acquiesced to his sacking. Lou, Nico and Sterling are of course unavailable for comment, while Doug Yule seems to have chosen not to contribute.

The film really comes alive with the input of Jonathan Richman – the St Paul of the Velvets church, still beatifically mystified at their majesty all these years later. In truth, a simple two hours of Richman talking about just a few of the “60 to 70” Velvets shows he saw would be a beautifully compelling film in itself. He’s spied, Where’s Wally-style, in striped T-shirt in a 1968 Boston Tea Party audience he winningly describes as composed of “Harvard professors, fashion models from New York, honest-to-God juvenile delinquents, bike gangs, Grateful Dead fans and nerds like myself…”

In the absence of much other musical or critical perspective, it’s fitting that it’s Richman who comes closest to capturing the magic of the band in full flight (“It was like being in the presence of Michelangelo!”). Very slowly he describes how, at the end of the swirling, roiling storm of Sister Ray, the band would abruptly cut off, the speakers would hum and “the audience would be dead silent for f-i-v-e seconds… And then they would applaud. The Velvet Underground had hypnotised them one more time.”