Saturday evening in Philadelphia, and in the basement of his house, Kurt Vile is giving a tour of the studio he built during lockdown. There are racks of guitars, an array of synths, a hulking ’60s German console desk in palest duck egg blue. “It’s like Abbey Road style,” Vile says, as we st...

Saturday evening in Philadelphia, and in the basement of his house, Kurt Vile is giving a tour of the studio he built during lockdown. There are racks of guitars, an array of synths, a hulking ’60s German console desk in palest duck egg blue. “It’s like Abbey Road style,” Vile says, as we stand and admire its wooden frame, its rows of buttons and knobs. “But it’s actual tubes, so it’s super-warm hi-fi.”

Among the musical machinery lies accumulated paraphernalia: a selection of false moustaches, a shot glass collection, homemade artworks with googly eyes, an alligator mask. There is a story attached to every object, every instrument – the red Farfisa keyboard, bought to capture the early Pink Floyd sound, was played on his 2015 track “I’m An Outlaw”. The console desk came from former REM engineer Mitch Easter. The compilation tapes with handwritten spines hail from the years Vile spent driving a forklift at the Philly Brewing Company. And the low armchair between those bootleg cassettes and his favourite synth was where he recently sought refuge during recording. “If I was feeling under the microscope, I’d just sit down right here and hide,” he says.

It has taken close to 30 years to accrue such apparatus, accoutrements, anecdotes. At the age of 42, Vile’s musical course runs back to his mid-teens, from recording joke songs and Beck wannabe tapes, to forming The War On Drugs with Adam Granduciel in 2005, and simultaneously pursuing a solo career that, since 2008, has included eight solo albums,

a collaboration with Courtney Barnett, and recordings with Dinosaur Jr, The Sadies, Steve Gunn and John Prine, among many. Along the way, he has honed a musical style that possesses a kind of laid-back prolificity; songs that at first might seem hazy and horizontal quickly draw into compelling classic rock tunes; long tracks grow mesmerising, their easy, unhurried gait studded with warm and mumbled wisdoms.

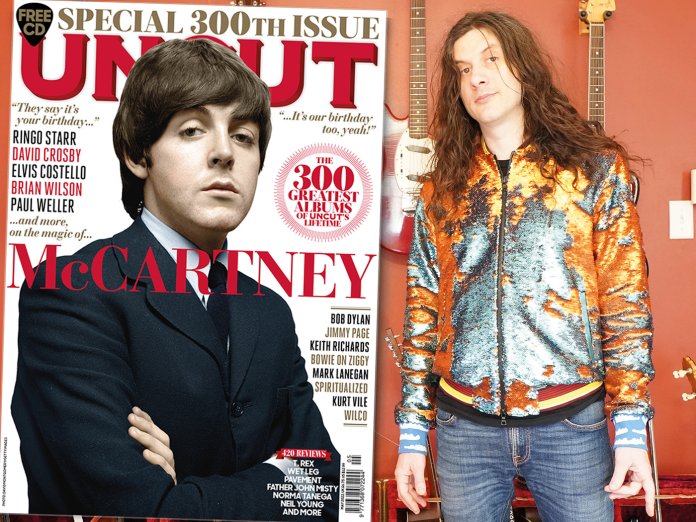

This evening, Vile moves nimbly around the studio in plaid shirt, jeans and beanie, pulling records from shelves and opening drawers to show me his journals, nodding to books he has read and loved – Nick Tosches’ Hellfire, Barney Hoskyns’ Hotel California, the unwavering majesty of Sun Ra: “I’ve been reading [John Szwed’s 2000 biography] Space Is The Place again and it’s insane,” he says. “It’s like the Bible.” He speaks with the giddy generosity of a music obsessive, darting from his love of Chastity Belt to The Fall, Terry Allen, George Jones, C+C Music Factory, Springsteen, Ween, ODB.

To spend time in Vile’s company is not so much to feel as if you are interviewing him, but rather as if you are inside one of his songs: the strange wiring of influences, the sinewy lope of his voice, the sense of the commonplace set beside the cosmic.