As with so many other things, Neil Young’s attitude towards bootlegs has been inconsistent, to say the least. An oft-circulated film clip from the early 1970s shows him angrily confronting a hapless record store clerk over a stack of unauthorised CSNY releases, eventually absconding with them, unp...

As with so many other things, Neil Young’s attitude towards bootlegs has been inconsistent, to say the least. An oft-circulated film clip from the early 1970s shows him angrily confronting a hapless record store clerk over a stack of unauthorised CSNY releases, eventually absconding with them, unpaid for. By the early 1990s, however, he had changed his tune. “More power to them – they can sell ’em in the parking lot, I don’t give a shit,” Young told biographer Jimmy McDonough. “I have nothing against bootlegs – for an artist like me, they’re essential.”

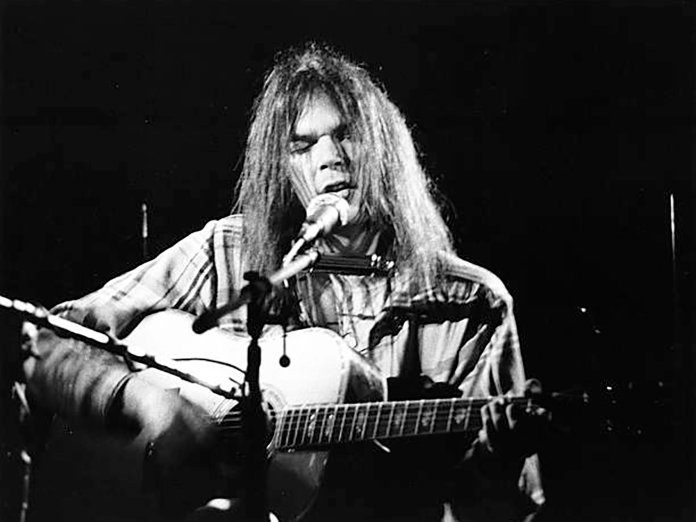

In the 2020s, Neil has leaned even further in the latter direction. Last year saw the launch of his Official Bootleg Series with Carnegie Hall 1970 (though in typically haywire fashion, this was in fact a previously un-bootlegged performance). Now, he’s released three more volumes, all solo acoustic, capturing two early 1971 concerts and one surprise small-club gig in 1974. Thanks to upgraded sonics (but retaining their charmingly amateur graphic design), they’re are all worthy additions to Young’s ever-expanding canon. But fans will almost certainly have a few quibbles about this latest batch of boots.

As Neil rightly notes, bootlegs have been essential for understanding and contextualising a career as long and varied as his. He’s played with a host of different bands, he’s gone through countless phases and side trips, he’s left entire albums unreleased for decades. Any die-hard will tell you Young’s officially released records tell only a fraction of his story (case in point: “Dance Dance Dance”, the only song on all three of these new Official Bootlegs, didn’t show up on a Young release until 2007).

However, with the release of two more 1971 acoustic shows, Neil can probably close the book on his post-Déjà Vu/post-After The Gold Rush solo era. Royce Hall, 1971 and Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 1971, recorded days apart, join the aforementioned Carnegie Hall 1970, Young Shakespeare, Live At The Cellar Door, and Live At Massey Hall 1971, all of which feature similar setlists. Throw in two earlier sets, Sugar Mountain – Live At Canterbury House 1968 and Live At The Riverboat 1969, and we’ve got a more than full portrait of Neil as a young artist, alone onstage. Taken on their own merits, Royce Hall and Dorothy Chandler are prime examples of Young in early ’71 … but maybe we can move on to other territory now? Future Official Bootlegs announced but now pushed back include a Tonight’s The Night-era gig at London’s Rainbow Theatre and a 3LP collection of recordings made in 1977 with Young’s virtually undocumented band The Ducks, plus Archives III, due this year.

Dorothy Chandler is the one to get; the 8+-minute “Sugar Mountain”, with numerous spoken-word digressions, is Neil at his most hilariously droll. The impossibly delicate “See The Sky About To Rain” may well be the definitive version of this underrated ballad. Finally, the snippet of “You And Me” (a song he wouldn’t finish until more than two decades later) that presages “I Am A Child” is the kind of thing that Shakey Heads live for. You’ve doubtless already heard the version of “Needle And The Damage Done” on Royce Hall — it’s this take that would later appear on Harvest.

Why is this period so important to Neil? “I loved it”, he told Cameron Crowe of his early ’70s solo tours. “It was real personal. Very much a one-on-one thing with the crowd.” That warm rapport comes across nicely on Royce Hall and Dorothy Chandler Pavilion – both venues are in the LA area, so they were virtually homecoming concerts for Neil. A reference he makes to the “memory of the Buffalo Springfield” at Royce Hall gets such a rapturous response that it’s safe to assume that many in the crowd had been there back in the Sunset Strip days. But these shows are no nostalgia trips, old bands notwithstanding. Maybe Neil sees this era as the point where he truly came into his own as a solo performer, with no need for the Springfield, CSNY or Crazy Horse.

Young’s fondness for the early 1970s might also have something to do with the fact that he had just met actress Carrie Snodgress, with whom he’d quickly fallen in love. By May of 1974, however, the bloom was off the rose for Neil and Carrie — and along with the legendary Homegrown (finally released in 2020), Citizen Kane Jr Blues (Live The Bottom Line) is a stirring document of his heartache in the wake of their dissolving love affair. “Here’s another bummer for you,” Young jokes at one point, before launching into an epically lonesome “Ambulance Blues”.

Neil was about to embark on an CSNY arena tour, but he dropped in unannounced to the 400-capacity Bottom Line in NYC to debut a set of mostly new, mostly downcast material. It’s a unique performance, with a wealth of rarely played material, from opener “Pushed It Over The End” to “Motion Pictures”, a song Neil has yet to play ever again (sacrilegiously, Neil has edited some of the original banter out). Even if devastation is the overarching theme of the new material, Young sounds alert and lucid, his guitar work precise, his vocals expressive. Thankfully recorded by taper Simon Montgomery, the Bottom Line bootleg was the kind of listening experience that turned casual fans into obsessives. Now remastered and officially part of Neil’s ongoing saga, its seductive power remains undimmed.