When people talk about Bob Dylan’s “born again period,” they can miss the point. If there was a determining spiritual rebirth, it didn’t happen in the late-1970s, but two decades earlier, when the Hibbing kid with a headful of Hank Williams and Little Richard vowed to dedicate his life to song. It became a never-ending baptism; he immersed himself in that river and never emerged, just swum deeper, followed the river to the sea and got tangled up in a polygamous marriage with all the siren mermaids. Speak to anyone who has spent time playing music with him, and chances are they’ll eventually tell you something like this: “Bob knows more songs than anyone I know.”

- ORDER NOW: Bob Dylan is on the cover of the latest issue of Uncut

- READ MORE: Bob Dylan, The London Palladium, October 20, 2022

- READ MORE: Bob Dylan, SEC Armadillo, Glasgow, October 30 & 31, 2022

- READ MORE: Bob Dylan, New Theatre, Oxford, November 4, 2022

- READ MORE: Bob Dylan – The Philosophy Of Modern Song

You should be careful what you rely on in his memoir, Chronicles, but you can believe Dylan when he writes in there about the fervour that gripped him as a young performer: “Songs to me were more important than just light entertainment. They were my preceptor and guide into some altered consciousness of reality, some different republic, some liberated republic.”

Speaking with Newsweek around 1997’s Time Out Of Mind, Dylan was unambiguous: “Here’s the thing with me and the religious thing. This is the flat-out truth: I find the religiosity and philosophy in the music. I don’t find it anywhere else.” He reiterated the point to The New York Times: “Those old songs are my lexicon and my prayer book. All my beliefs come out of those old songs […] You can find all my philosophy in those old songs.”

But what kind of religion, what philosophy is this? The answer comes blowing like a desert wind through the 300-odd pages of his genuinely extraordinary new publication, The Philosophy Of Modern Song.

When it was first announced, this book, billed as Dylan writing “essays focusing on songs by other artists,” sounded intriguing enough. But even those who knew to take that description with a pinch (or a pillar) of salt might be unprepared for what lies between the covers. Glancing at the contents page tells you Dylan writes about Marty Robbins’s light, waltzing 1950s pop-western ballad “El Paso”. But it doesn’t set you up you for lines like this: “In a way, this is a song of genocide…” Similarly, knowing that there’s a chapter on Webb Pierce’s 1953 recording of “There Stands The Glass” doesn’t lead you to expect a nightmare jam on the My Lai massacre that leads to the image of a dead astronaut buried in a Nudie suit.

There are sixty-six songs covered – and it’s the kind of book that leaves you twitchy and itchy wondering just why that particular number was chosen – ranging across the musical map without any obvious design, from Carl Perkins’ “Blue Suede Shoes” to Johnnie Ray’s “Little White Cloud That Cried”; from “London Calling” to Nina Simone owning “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood”.

Sometimes, in passing, Dylan offers concise, almost-straight pen-portraits of the singers and writers in question, sketching out touching tributes to the likes of Townes Van Zandt and John Trudell, the cosmic greatness of Little Walter. Mostly, though, his essays are strange, hypnotic sermons: “The song of the deviant, the pedophile, the mass murderer,” he suddenly lets fly over Rosemary Clooney’s kooky mambo “Come On-A My House”.

Often the chapters are split into two sections, with the consideration of the song prefaced by a riff that looks to get inside the feel of it, like warm-up exercises for a method actor building a character, or an attitude of performance. Some of these are just hilarious, like the relentlessly escalating incantation explaining exactly how extremely mighty and not-to-be-trod-upon those blue suede shoes actually are. Many more become intense, obsessive little narratives, delivered in a voice that suggests a defrocked hellfire preacher caught in a doomed noir parable. “Desire fades but traffic goes on forever,” muses the drained, desperate protagonist of the perfect micro-fiction Dylan offers up to serve Ray Charles’ “I Got A Woman”.

The night time in the big city feel marks this as a development from Dylan’s Theme Time Radio Hour show. His collaborator on that, Eddie Gorodetsky, is thanked up front, and the Theme Time vibe is unavoidable in the audiobook, with Dylan’s host joined by an all-star gallery of narrators including the Big Lebowski reunion of Jeff Bridges–John Goodman–Steve Buscemi alongside giants like Rita Moreno and Sissy Spacek.

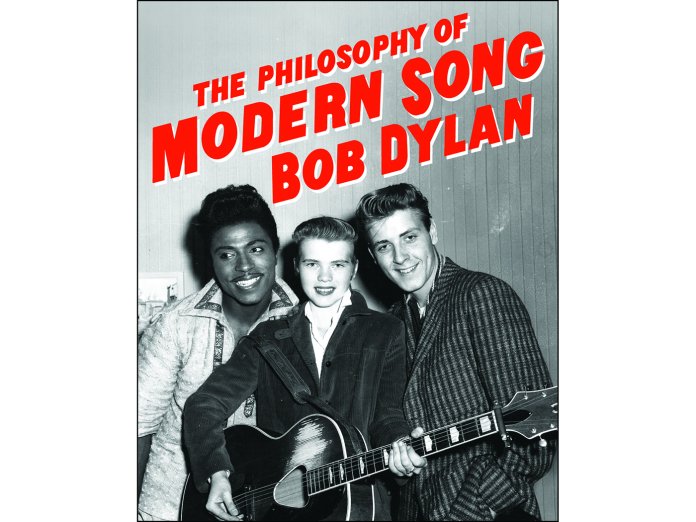

But the physical book, quite beautifully designed by Theme Time’s Coco Shinomiya, is the prime artifact. Dylan’s copious illustration selections build a parallel world that sets his words vibrating, while guarding their secrets, and cracking weird deadpan jokes. None of the images are captioned. You either know that’s Sam Cooke with his arm around Gene Vincent, or you don’t. You pick up Julie London calling on the telephone, or not. Deborah Kerr and Burt Lancaster roll eternally in their surf, Jack Ruby steps in when you least expect, Richard Widmark goes for his gun, Johnnie Ray crumbles up and cries, and, yes, there goes Supercar soaring into the blue.

Other names recur repeatedly in the text – Frank Sinatra becomes a particularly persistent phantom – but the figure you almost catch sight of most here is Bob Dylan himself, slipping between pages like a fugitive reflection in a shattered hall of mirrors. The mischievous feeling that he’s writing about himself – or, perhaps, all the ideas of himself he’s had to put up with – flickers again and again, and not merely when he suggests Elvis Costello “had a heady dose of Subterranean Homesick Blues” while writing “Pump It Up”.

“There’s lots of reasons folks change their names,” Dylan offers, while discussing Johnny Paycheck. “Like with many men who reinvent themselves, the details get a bit dodgy in places,” he writes about the “Ukranian Jew named Nuta Kotlyarenko.”

Want to know what Dylan thinks about divorce? About getting old? About switching style? About alienating a fanbase? How it feels to try and explain a song? Why he tours so much? It’s all here, or seems to be. Wonder what happened to the protesty guy? Well, here he is, comparing modern times to a fat undernourished child, or pretending he’s writing about Edwin Starr’s “War”: “And if we want to see a war criminal all we have to do is look in the mirror.”

Serious, playful, insightful, outrageous, disturbing, hilarious and sly, foul-mouthed and angelic, steeped in blood and lusty thoughts, it’s less musicology than a gnostic gospel with a literary tap-dancing routine thrown in. It’s a church built in a funfair, filled with trapdoors. It’ll set your hair on fire.

The Philosophy Of Modern Song by Bob Dylan is published by Simon & Schuster