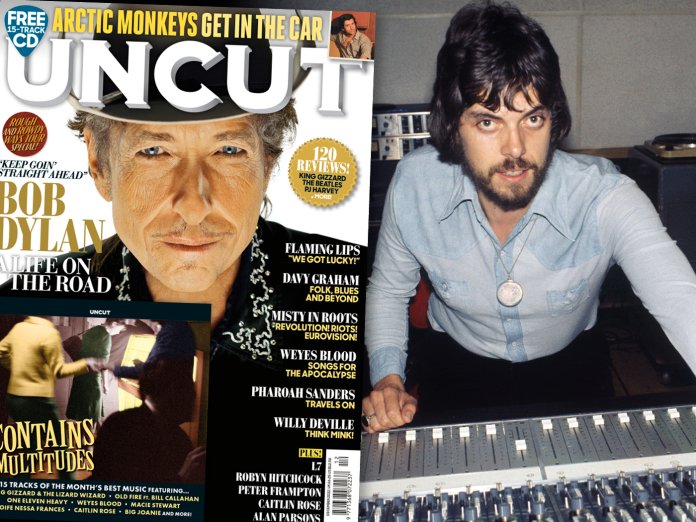

The ultimate backroom boy Alan Parsons on his massively successful “prog pop” career, and takes us back to revisit the albums that were influential to him, in the latest issue of Uncut magazine – in UK shops from Thursday, October 13 and available to buy from our online store. For an artis...

The ultimate backroom boy Alan Parsons on his massively successful “prog pop” career, and takes us back to revisit the albums that were influential to him, in the latest issue of Uncut magazine – in UK shops from Thursday, October 13 and available to buy from our online store.

For an artist who has sold in excess of 55 million albums worldwide, Alan Parsons is not a face you’d immediately recognise. “It’s because we never played live, so no-one ever saw me!” he says. “Frankly, I was pretty happy not being recognised. I saw what other artists had to deal with, and it was madness. Poor old Paul [McCartney] couldn’t go to restaurants or clubs. He couldn’t even be in his own house in Sussex – he’d have fans breaking through the fences to get a look at him!”

Parsons has always been comfortable as a backroom boy. After dropping out of school at the age of 16 he embarked on an EMI training scheme before working as a “balance engineer” at Abbey Road studios, where he assisted on key recordings by The Beatles, Pink Floyd, The Hollies and Wings, and later produced huge hits for the likes of Steve Harley, Pilot, Al Stewart and John Miles. But it was The Alan Parsons Project, established in 1976 with the Scottish musician Eric Woolfson, that made his name. Their works weren’t so much concept albums, more audio musicals, themed around single subjects, including albums based on Edgar Allan Poe, Isaac Asimov, Antoni Gaudí and Sigmund Freud. After 11 studio albums – which next month are gathered into a new boxset, The Complete Albums Collection – Parsons and Woolfson split in 1990, but Parsons has continued solo, even finally taking his music on stage. “It’s not really prog rock,” he says. “I’ve always seen it as prog pop.” Here, he takes us through his remarkable catalogue – starting with a rite of passage at notable addresses in Mayfair and St John’s Wood.

THE BEATLES

ABBEY ROAD

APPLE RECORDS, 1969

A baptism of fire for the teenage studio engineer

I started working at Abbey Road as a tape operator in October 1968, at the age of 19, and the Let It Be sessions were one of my first jobs. I was sent down to the Apple Corps studios in Savile Row in the absence of Apple’s own operational staff. I don’t appear in the original Let It Be film, but I’m in shot for a total of about 10 seconds in Peter Jackson’s Get Back, which is a thrill! My job was to keep the tape rolling and replace it when needed. The Beatles were literally recording all the time during these sessions. But it was a month later, at Abbey Road, that was the more technically complex job. Unlike Let It Be, Abbey Road was a proper studio album, like Sgt Pepper, made with great precision. The band members would record separately, usually in Studio 2, at all hours, and they always needed

to be covered by tape ops. There were seven or eight of us in total. I remember Paul doing endless takes of “Oh! Darling”. I remember George doing “Something” and “Here Comes The Sun” on his own. I remember John doing “Polythene Pam” and also coming in while I was doing the final mix of “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” and telling me to cut it dead rather than fade it out!

My line manager was Geoff Emerick, who was a genius. I remember how he got that fluttering effect on the synth sounds on “Here Comes The Sun” by threading sticky tape around one of the pressure rollers on the tape player, so it was literally juddering all the time.

The band were clearly working very separately by that stage. You barely saw all four of them together until the day they did the zebra-crossing shoot.

PICK UP THE NEW ISSUE OF UNCUT TO READ THE FULL STORY