Think of a song, not any particular song, just the idea of a song. Say it’s the late 1970s when Laraaji was roaming the streets and parks of New York with his electrofitted autoharp. A song with its anticipated structure and its lyrical text is there to tell you about an experience. Laraaji’s mu...

Think of a song, not any particular song, just the idea of a song. Say it’s the late 1970s when Laraaji was roaming the streets and parks of New York with his electrofitted autoharp. A song with its anticipated structure and its lyrical text is there to tell you about an experience. Laraaji’s music is the experience.

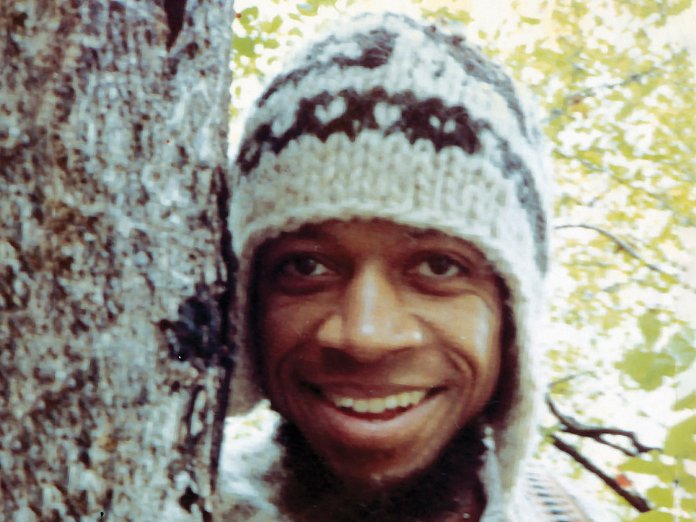

The life of Edward Larry Gordon, born in Philadelphia in 1943, appears to have been one long chain of serendipity. Raised in New Jersey, he sang in Baptist church choirs as a kid before studying piano at Howard University. A talent for performing, comedy and role play brought him to Harlem’s Apollo Theatre, where he acted as host in the mid-’60s, while also serenading legendary boho hangouts Café Wha?, the Bitter End and the Village Gate with his folkish songbook. He even scored a role as long as a goldfish recall in Robert Downey Sr’s cult ad-men madness movie Putney Swope in 1969. But this is all ancient prehistory.

A little more sand runs through the hourglass and we’re in Washington Square Park, circa 1975. Ed Gordon is by now entrenched up to his scapula in the cosmopolitan alternative lifestyle movement in which everything from yoga and meditation to pot, improvised music and barefoot dancing is involved. His guitar has been pawned and in its stead an autoharp purchased on impulse. Jenny Lynch is passing by in the park and likes what she hears emanating from the autoharp, which he has stripped of its chord bars and amplified with an electric pickup. He taps and strums the pentatonic-tuned wires with chopsticks, brushes and metal slides. Jenny is a luthier who just built a hammered dulcimer for folk musician Dorothy Carter. She writes down his number, recommends him to Carter, and before you know it he’s accompanying her and running workshops on ‘electronic autoharp experiments with tuning and phase shifters’ at the 1976 Boston Globe Jazzfest and Music Fair.

The year 1976 is an epochal time for the age of Aquarius. Progressive music, radical psychiatry and alternative medicine melt together in a quiet counterculture-shock known as New Age. A transitional flap on the mystical wing of popular culture. Hippiedom’s last sigh, impotently puffing a farewell reefer as synths and sinewaves are swung up over the ocean. The dawning of a musical age impossible to imagine even just a handful of years back at Monterey and Woodstock.

This moment is Ed Gordon’s moment. Ed Gordon, Larry G, Laraaji – a morphology of name and identity in mirror sync with his expanding musical consciousness. Punks in dark clubs and dives snarl about music and society being on a road to nowhere. For Laraaji (and fellow voyagers) music is a healing force, a pathway to the mindful zone, a daily microdose of aural Ambien. On the two unbroken sides of Celestial Vibration from 1978, he made a record of the sort of stardust he was sprinkling around at creative dance companies, holistic drop-in centres and yoga classes at that time. “Bethlehem” and “All-Pervading”, 24 minutes each, only cease because the needle must skate to the stillpoint at the centre.

They’re both here at the start of Segue To Infinity, the first of four discs. The rest are parts of this period of Laraaji’s history we’ve never heard before. They are taken from ultra-rare acetates – spotted on eBay by a sharp-eyed collector. The mint A++ white labels, credited to Edward Larry Gordon, had been retrieved from a storage unit, sold at a flea market and finally offloaded online where a college student recognised the name and made a winning bid of $114. They are now in the safe hands of the archive label Numero Group, who have form when it comes to independent and private-press New Age re-releases.

Celestial Vibration has been aired once already on Soul Jazz Records. The remaining dug-up tracks won’t disappoint anyone familiar with Laraaji’s blissful lakes of kundalini stretching beneath billowing cumulonimbi of bliss. “Ocean” would be the ideal headphone accompaniment for standing too close to a Rothko canvas. A deep enveloping background accented with scudding strokes on the zither strings. “Koto” is composed of similar sonic ions, signposting the way ahead to beatless milestones like Steve Hillage’s Rainbow Dome Musick – which in turn thumbs its way towards The Orb and other ’90s ambient noodle bowls.

So far so rapturous, but the three tracks titled “Kalimba” provide the real revelations in this collection. Here Laraaji uses the zither both as a drum and a marimba. The first of them is 18 minutes, the others upwards of 22. These are audibly a far more physical test of endurance than the other tracks here. Thrumming sequences falling somewhere between central African logdrum rituals and one of Can’s Ethno-Forgery jams. He keeps up a meditative yet somehow surging two-handed groove, striking rattling blows on the strings with wooden or metal beaters roughly four to six times per second. These “Kalimba” pieces are the most exciting addition to Laraaji’s canon – beautiful, intricate little cosmic clockwork mechanisms that must have been mesmerising to observe while they were being played. The track “Segue To Infinity”, that gives its name to the boxset, pairs Laraaji’s orcabone harp tones with lark-ascending flute from Richard Cooper. It’s the one that conforms to the most recognisable ‘New Age’ tropes although is still vastly more appetising – and less kitsch – than most of what you’ll hear on the stereo down your local crystal-and-tarot boutique.

Down on the street, Laraaji visualises his ideal record producer. The universe makes it so. A scrap of paper left in his zithercase in 1979 contains a phone number. At the end of the line is Brian Eno. Sleevenotes by Vernon Reid of Living Color, who has known Laraaji since the ’70s, and Numero Group archivist Douglas McGowan, perform admirable detective work without being able to conclude exactly when, where or for what precise purpose these unearthed tracks were recorded. Irreconcilable facts place them either just before or just after the 1980 release of Ambient 3: Day Of Radiance on Eno’s EG label.

In any case, these beautiful, vaporous exercises in musical mindfulness restored to us on Segue To Infinity are convincing proof that Laraaji didn’t need any Eno to help him read the map.