Gentle, revealing performances from the eye of Neil Young’s 1970 storm... A certain air of serenity pervades the latest of Neil Young’s archival live releases, culled from performances at Washington, D.C.’s Cellar Door in late November and early December of 1970. That calm may be misleading: just after his stand at the Cellar Door, he stormed out of a concert at Carnegie Hall, annoyed by raucous fans who’d sneaked in via the fire exits. As Young later explained, “It was an intermission -- I just took it a little early.” No one can blame the singer for feeling tired and emotional. After all, he’d just turned 25 and the brief tour that included the Cellar Door stint capped off a year that was eventful even by his standards. With the release of CSNY’s Déjà Vu and the immediate impact of the hastily written “Ohio,” Young experienced his first taste of mega-stardom as well as the sour side of life in the supergroup, which marked the end of its tour in July with one of its customary acrimonious collapses. The boost in profile helped Young attain his first real commercial success as a solo artist with the late-summer arrival of After The Gold Rush. Having decamped from L.A.’s studios for his inaugural home set-up, he’d also been building up a massive trove of recordings with Crazy Horse, then firing on all cylinders with guitarist Danny Whitten and keyboardist Jack Nitzsche both still on board. On the personal front, matters were stormier due to the collapse of Young’s marriage to Susan Acevedo. And not long after the tour wrapped in December, he’d suffer a slipped disc while working in the garden, an injury that would leave him in a back brace for many months to come. Yet all of this tumult was either on the horizon or somehow out of the frame in the performances collected for Live At The Cellar Door. The 13 songs were originally recorded for a live album that was also slated to include material from Crazy Horse’s blazing sets at the Fillmore East in March. One of the three new songs to make their live debuts during the solo tour was “Old Man.” With Young delivering its opening lines in an almost tentative murmur, the future Harvest standout evinces a vulnerability that would be replaced by a more confident tone by the time of the performance on Live At Massey Hall 1971, recorded less than two months later. A rarity that would not get any official release until the Massey Hall disc, “Bad Fog Of Loneliness” is an affecting expression of his post-divorce inner turmoil. “So long, woman, I am gone/ So much pain to go through,” he croons. Yet his bravado immediately evaporates in the plea that follows: “Come back, maybe I was wrong.” Other Cellar Door selections reinforce the notion that Young’s always been at his most plaintive when at the piano. “I had put it in my contract that I’d only play on a nine-foot Steinway grand piano just for a little eccentricity,” he quips during the banter that opens a wistful “Flying On The Ground Is Wrong”. Elsewhere, his liberal use of the sustain pedal deepens the ache in “After The Goldrush”. More startling is the transformation of “Cinnamon Girl”, heard without the big dumb thunder of its iconic guitar riff. With Young hammering away at the ivories instead, it might’ve passed for a jaunty Tin Pan Alley-style vamp if not for the edge of sorrow in his voice. There’s a quality of softness, too, something that’s palpable throughout the performances. Its presence is surprising for an artist who was always a little too steely to ever be mistaken for a sensitive folkie. There are many sterling moments to escape from Young’s vault – but none seem quite as unguarded as the best ones here. Jason Anderson

Gentle, revealing performances from the eye of Neil Young’s 1970 storm…

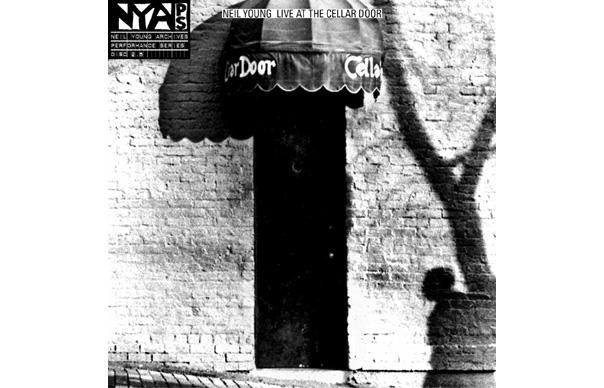

A certain air of serenity pervades the latest of Neil Young’s archival live releases, culled from performances at Washington, D.C.’s Cellar Door in late November and early December of 1970. That calm may be misleading: just after his stand at the Cellar Door, he stormed out of a concert at Carnegie Hall, annoyed by raucous fans who’d sneaked in via the fire exits. As Young later explained, “It was an intermission — I just took it a little early.”

No one can blame the singer for feeling tired and emotional. After all, he’d just turned 25 and the brief tour that included the Cellar Door stint capped off a year that was eventful even by his standards. With the release of CSNY’s Déjà Vu and the immediate impact of the hastily written “Ohio,” Young experienced his first taste of mega-stardom as well as the sour side of life in the supergroup, which marked the end of its tour in July with one of its customary acrimonious collapses.

The boost in profile helped Young attain his first real commercial success as a solo artist with the late-summer arrival of After The Gold Rush. Having decamped from L.A.’s studios for his inaugural home set-up, he’d also been building up a massive trove of recordings with Crazy Horse, then firing on all cylinders with guitarist Danny Whitten and keyboardist Jack Nitzsche both still on board.

On the personal front, matters were stormier due to the collapse of Young’s marriage to Susan Acevedo. And not long after the tour wrapped in December, he’d suffer a slipped disc while working in the garden, an injury that would leave him in a back brace for many months to come.

Yet all of this tumult was either on the horizon or somehow out of the frame in the performances collected for Live At The Cellar Door. The 13 songs were originally recorded for a live album that was also slated to include material from Crazy Horse’s blazing sets at the Fillmore East in March. One of the three new songs to make their live debuts during the solo tour was “Old Man.” With Young delivering its opening lines in an almost tentative murmur, the future Harvest standout evinces a vulnerability that would be replaced by a more confident tone by the time of the performance on Live At Massey Hall 1971, recorded less than two months later. A rarity that would not get any official release until the Massey Hall disc, “Bad Fog Of Loneliness” is an affecting expression of his post-divorce inner turmoil. “So long, woman, I am gone/ So much pain to go through,” he croons. Yet his bravado immediately evaporates in the plea that follows: “Come back, maybe I was wrong.”

Other Cellar Door selections reinforce the notion that Young’s always been at his most plaintive when at the piano. “I had put it in my contract that I’d only play on a nine-foot Steinway grand piano just for a little eccentricity,” he quips during the banter that opens a wistful “Flying On The Ground Is Wrong”. Elsewhere, his liberal use of the sustain pedal deepens the ache in “After The Goldrush”. More startling is the transformation of “Cinnamon Girl”, heard without the big dumb thunder of its iconic guitar riff. With Young hammering away at the ivories instead, it might’ve passed for a jaunty Tin Pan Alley-style vamp if not for the edge of sorrow in his voice.

There’s a quality of softness, too, something that’s palpable throughout the performances. Its presence is surprising for an artist who was always a little too steely to ever be mistaken for a sensitive folkie. There are many sterling moments to escape from Young’s vault – but none seem quite as unguarded as the best ones here.

Jason Anderson