This article originally appeared in Uncut Take 287 (April 2021)

“I think I called him Serge Bourguignon,” says Jane Birkin, recalling her first meeting with Gainsbourg on the set of the film Slogan in 1968. “He was quite vexed that I didn’t know who he was, so not long after that he gave me a book called Chansons Cruelles, ‘cruel songs’. It was a little leather volume with some of his lyrics, and in it was written, ‘For Jane B, with whom I’ll write Histoire De Melody IE Nelson.’ Right from the beginning he knew that he’d write this.”

Released in March 1971, Histoire De Melody Nelson did little to trouble the charts in France or abroad, but its reputation as a stunning and unique piece of work has grown immeasurably in the half-century since. Now, 30 years after Gainsbourg’s death, the influence of its knotty orchestral funk-rock is more potent than ever.

“The whole poetry of the thing is so incredible,” says Birkin, “I thought people would be screaming for it and that it would be a hit immediately. It wasn’t the case, we had to wait. Serge handed the gold record over 20 years later and said, ‘Well, at last we got it.’ But it took a long time.”

To record this Lolita-inspired concept album about a young girl from Sunderland and the Parisian man she meets, Gainsbourg and arranger/co-writer Jean-Claude Vannier tapped up their favourite London session musicians, notably guitarist Alan Parker and Dave Richmond, veterans of previous hits such as “Je T’Aime… Moi Non Plus” and “69 Année Erotique”.

“He recorded in the UK because of how we could work,” explains Parker, “what we were capable of. Serge said British musicians were the best, and that’s why there’s sometimes been a bit of disgruntlement in Paris with him not using French musicians. He was forever smoking when I knew him, and he drank quite a bit and he enjoyed it, but it didn’t make him nasty or aggressive, he just carried on as he was – the laid-back Serge, as we called him.”

The album begins with “Melody”, seven and a half minutes of hallucinatory grooving rock, a different take of which formed the bedrock for the LP’s closing track, “Cargo Culte”. The work of the British musicians is enhanced by Jean-Claude Vannier’s Paris-tracked orchestral work, while Gainsbourg and Birkin’s spoken word outlines the tragic tale of Melody, the narrator, his Rolls-Royce and all.

“In Melody Nelson there are no tunes, not like a normal pop song,” says Jean-Claude Vannier. “On ‘Melody’, the melody is only [from the] orchestra.”

“It was inspiring stuff,” says Birkin, “and it was a divine time – [Birkin’s first daughter] Kate was tiny, I was having Charlotte and all was well with the world, it seemed to me. My parents and Serge had kicked it off so extraordinarily well after such a disastrous marriage with John Barry, and I’d fallen in love with Paris and this extraordinary man… Russian, Jewish, funny, sad, a poet. It was incredible. And such good fun!

“It’s 30 years since he died this year, and Charlotte’s finally opening up his house as a museum. It’s like sleeping beauty, nothing has moved since the night he died – I don’t know anyone who doesn’t want to get in there.”

____________________

JANE BIRKIN (vocals): I used to film quite a lot of rubbish, and Serge thought doing films was a dangerous metier, so he would come along always and take a suite in beautiful hotels, if they were beautiful, or get really angry if he was in a squalid hotel, which was more often the case. He used to say it was too beautiful to write at home in the Rue de Verneuil. At the end of his life he was writing a song a night, but in Melody Nelson days he took his time. The piano and the themes and the music he did with Vannier.

JEAN-CLAUDE VANNIER (arrangement, orchestra direction): We were very close friends. We would work all the time. I first met him in London. He lived in Chelsea at this time – in Cadogan Hotel, a big hotel where Oscar Wilde spent his last night before going to jail – and we began to work together doing the music for a French movie, [1970’s] Cannabis.

BIRKIN: Serge always found great orchestras, he had Michel Colombier for the first version of “Je T’Aime…”, and that was pretty fantastic, and he did a lot with him, and he had Arthur Greenslade, and then it moved to Vannier after that, and to Alan Hawkshaw an awful lot in England [later]. Vannier was very important for Serge, because his orchestrations provided an oriental colour that has never dated.

VANNIER: After Cannabis, Serge said, “We have a new project, it is called Melody Nelson.” I said, “What is it?” He said, “I only have the title. I don’t know what it is yet.”

BIRKIN: As he was in London [with Birkin’s family] for all Christmases and Easter, and summer holidays on the Isle Of Wight, [the name] Nelson was quite normal for him [by then].

VANNIER: He said, “Have you some music in your drawer?” And I gave him some music for songs. I wrote the orchestra, parts of melodies, and some ideas. He would sing the melody to me, and then play chords on the piano.

ALAN PARKER (guitar): They were great days. I did the original “Je T’aime…” with Brigitte Bardot. That was my first encounter with Serge, and as we got on so well he booked me for this and for that.

BIRKIN: It was so charming to see Alan and Serge together, they complimented each other terribly and he was such a comforting figure for Serge. He loved working with those musicians.

PARKER: So many massive hits were done at the Phillips studio: The Walker Brothers, Dusty Springfield and so on. I’ve recorded there when you couldn’t put a pin between musicians. In those days it all went down in one, so there was a lot of pressure on everyone, particularly the engineer – you could remix it, but there was so much spill you couldn’t do much.

DAVE RICHMOND (bass): It was underground, you went down stone steps to get there, like a cellar really. But when you got down there it was very plush.

PARKER: We created that Melody Nelson sound? Yes, in a way. It was never a case of “I want this sound” or “I want that sound”, he wasn’t like that, Serge. He would say, “I want it rougher, or very sympathetique”… We were used to it – you’d have to be a semi-mindreader and come up with things until it was perfect.

RICHMOND: I think it was Barry Morgan on drums, but no-one knows for sure. We didn’t use a click track much then, apart from for film scores, and Barry’s timing was extremely good.

VANNIER: I wrote out detailed arrangements. I like improvisation in jazz, Monk, Miles Davis and so on. But in my sessions, I’m very afraid that if I let musicians improvise they will play like they are on another record. And I don’t want to have problems with that. So I write very particularly… In Melody Nelson, there is an amount of improvisation, but very light.

PARKER: With Serge a lot of it was improvisation. Vannier said he wrote it all, that’s absolute bunkum, of course he didn’t – he gave us guidance, if you like, on behalf of Serge, but then Serge also chipped in, in his way.

RICHMOND: Can you imagine it all written out?! If we’d had a part written like that I wouldn’t have been able to read it to play it! With all the bends, it would have been horrendous to read.

PARKER: There might have been one bar of an example style and then just chords – you see what they’re getting it, and then you adapt it.

RICHMOND: They just left us, me and Alan, improvising on this continuous drumbeat until they told us to stop. They might have indicated when they wanted a fill, or to bring it up or down a bit.

PARKER: Most of the time Vannier stayed in the control room, and it was Serge in the studio getting across what he wanted. The way Serge would describe things was emotion: “I want tension here, lust there.” Regarding the orchestration, we didn’t have a clue because that was being put on later. What we delivered could have interfered with some of Vannier’s orchestral lines – but it wasn’t our fault because we didn’t know what those lines were. I used a Gibson Les Paul Standard – I’ve still got it – and my Fender Deluxe Reverb with a little preamp built into it, feeding into the main amp. The feedback on “Melody” was controlled by how close I was to the amp, which way I was facing. Yes, it’s hard to control – you find a position and it’s not comfortable to play or sit in, but you tolerate it just to maintain the feedback.

RICHMOND: I was using my Burns Bison bass. I had played double bass in Manfred Mann, but someone told me there was work for electric bass players, so I went to buy an electric bass from Denmark Street. My wife said, “Oh, that looks a nice one”, because it was very impressive-looking, and that was that. But fortunately it turned out I was the only session musician using a Bison, everyone was on Fenders of various types. It was very good for that ‘click sound’ – everyone was asking for a click bass then and I became known for it. Once we’d recorded, Serge would take the tracks back to France and finish them there with Vannier.

VANNIER: After the music was recorded, he wrote the lyrics. He always saw it as a film. A film without pictures. A film in the head.

BIRKIN: Melody is a 14-year-old girl on a bike, and he’s in his Rolls-Royce – Serge did have a Rolls-Royce, he bought one after we did two films in Yugoslavia, just before I had Charlotte. We did Romance Of A Horse Thief, and having done that, we did another film [Ballade à Sarajevo], where Serge was supposed to be the head of a resistance army in Yugoslavia, if you can imagine, and I was playing a nurse. We held up the whole Nazi army by me coming out of a frozen lake and Serge gunning them down with a machine gun from behind. Serge got paid in cash, and when we got back to Paris it gave him a kick to think that with money from a communist country he was going to buy himself a Rolls-Royce. So off he went to Rolls-Royce in Paris and he found one with one of the Rs in red. It was very rare, it looked like a car from The Avengers. We needed a chauffeur to drive it because Serge didn’t have a license – so he unscrewed the radiator tap where it had the ‘spirit of ecstasy’ on it, and he put it on his mantelpiece. Of course, “Melody” mentions “Silver Ghost” and “spirit of ecstasy”, so he was probably thinking about it while we were in Yugoslavia and just after.

VANNIER: Melody Nelson is a dream, you know. But I don’t think it was a good thing to put pictures on the music [in the short film Melody, made to accompany the album]. If you see the girl, it is dead. The film is not very good, I think, and I believe that Serge felt the same way as me.

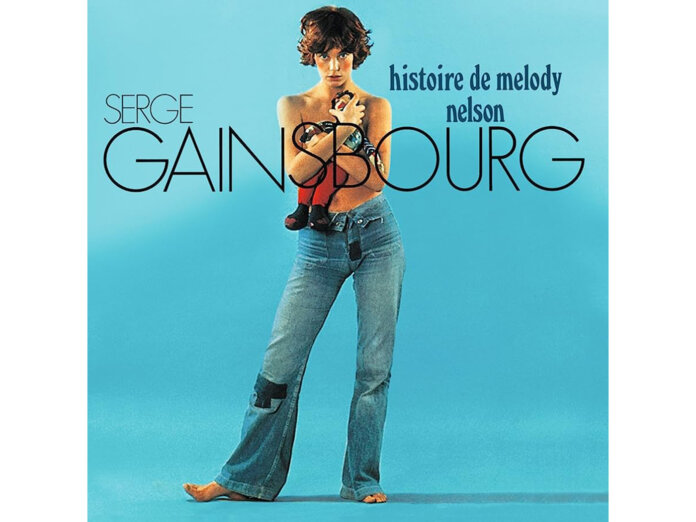

BIRKIN: In Tony Frank’s lovely photo for the cover, Serge made me wear a red wig and paint on freckles on my nose. I had red hair because my best friend Gabrielle Crawford’s daughter Lucy had red hair, and so he wanted Melody to have red hair and freckles – I think he was terribly influenced by Lolita by Nabokov. I held up my monkey so you wouldn’t see that I’d opened my jeans because I was four months pregnant.

VANNIER: The album is very far out. At the time, in the 1970s, the LP was not a success, and we passed on to other things. I don’t know what happened. It is strange for me. I liked to play, to work with Serge, he was a very close friend, and we had the pleasure of writing this album.

PARKER: Serge and I got on very well, without a doubt. When I lived in Surrey I had a studio at home, and that’s where we recorded some of that last album we did with Jane [1990’s Amours Des Feintes]. When we recorded the music for that album it was in the winter and I lived very high up on the North Downs then, there was snow and everything, and Serge arrived in his trademark no-socks and these little white leather plimsolls. “Aren’t you cold?” “No, no…” You could see, poor sod, he was shivering! But he got into his Pernod and his Gauloises, and he was ok.

RICHMOND: Until a few years ago I’d forgotten all about Histoire De Melody Nelson. I had no idea it was a cult record, I’d never bought it, never heard it until a few years ago. Now I think it’s brilliant!

BIRKIN: In those days, songs that were number one were never ours. Serge was immensely popular, but at the same time he wasn’t number one, number one was people like Claude Francois, so [it was typical] that he would write this opus and it should be recognised but not be the bestseller. He was always 20 years ahead of his time. The comfort to me is that by the time he died he knew that he was the most popular man in France.