An engaging look back at an inspiring backstory through the eyes of the band's founding friends

An engaging look back at an inspiring backstory through the eyes of the band’s founding friends

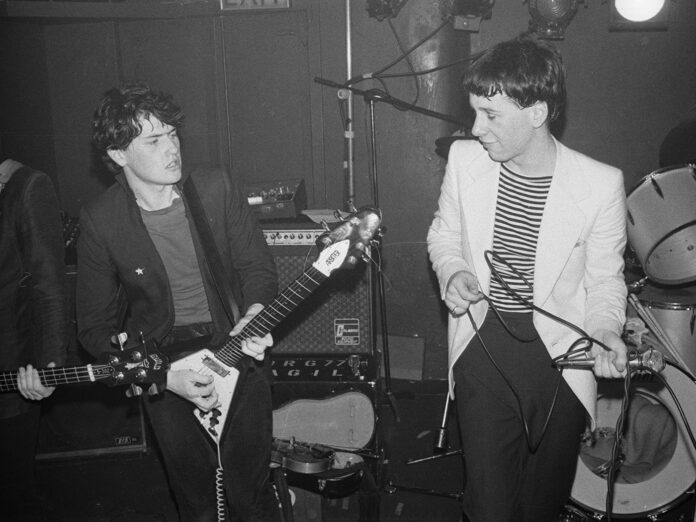

As Jim Kerr and Charlie Burchill prepared to tour their latest version of Simple Minds – described by Kerr in the film as being as much of a “theatrical ensemble” as a traditional band – Joss Crowley’s film goes back to the start, when the pair met in a building site at their new flats in Toryglen in Glasgow – a city “in a rush to modernise” as Kerr recalls.

TALKING HEADS ARE ON THE COVER OF THE NEW UNCUT – HAVE A COPY SENT STRAIGHT TO YOUR HOME

Kerr and Burchill, still great pals, return to Glasgow throughout the film, emphasising the importance of the city on their development, particularly how it gave focus to their own monumental ambition. Kerr visits the Carnegie Library in Govanhill, where his father encouraged him to read to flee the limitations of working-class life in a post-industrial city. Burchill visits Southside Music, where he bought opportunity in the form of guitars and strings. Later, they both stroll down to the Clyde to discuss the writing of “Waterfront”. But much as they recognise and appreciate the city’s role in their formation, it’s clear that Glasgow equally represented a place from which to escape. Simple Minds, and Kerr in particular, were hugely driven, and their work ethic – their determination to achieve success and their desire for continued improvement – is astonishing.

While many music documentaries take a more romantic approach to creativity, with success almost the afterthought, this is very much a different beast. That’s not to say that Simple Minds were mercenaries driven solely by success, as both Graeme Thomson’s excellent biography Themes For Great Cities and this documentary illustrate. It is interesting to learn about the recording of those early albums, particularly 1980’s magnificent Empires And Dance, as the band experimented and explored, shifting from punk into new wave through disco punk until they settled into a more masculine version of New Romantic. Well-chosen talking heads – Muriel Gray, Bobby Gillespie, Bob Geldof – add context, while there are contributions from other band members, managers, producers and Mariella Frostup, who was tape operator (credited as Mariella Sometimes due to her unreliability) on second album Real To Real Cacophony.

The UK breakthrough of “Promised You A Miracle” in 1982 was followed by international success with “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” in 1985, a song the band were initially reluctant to record but then made entirely their own – before it catapulted them into MTV stardom on the back of The Breakfast Club soundtrack. That same year they were invited by Geldof to play Live Aid – tellingly in Philadelphia rather than at Wembley – where they were introduced by Jack Nicholson and had the chutzpah to open with a new song, the terrific “Ghost Dancing”. Simple Minds were now consciously writing for arenas, in their own rush to modernise.

Seemingly on top of the world, they were paired with producer Jimmy Iovine, who wasn’t impressed and told them so. They rose to the challenge set by his no-nonsense, pugilistic approach by writing “Alive And Kicking” and then recording the mega-selling Once Upon A Time. Kerr’s delight in being stretched is tangible, but this marked their commercial high point. Having achieved their dream, Simple Minds lost direction. Street Fighting Years was a dramatic change in sound – too dramatic for American, which lost interest – and a gradual decline set in. They limped through the 1990s.

Kerr, semi-retired in Sicily, learnt Italian and sponsored a local football team on the condition they switched kits from blue to green-and-white hoops – interestingly, the only time Glaswegian sectarianism is mentioned throughout the film. But what happens when an ambitious group loses their drive and finds themselves playing half-empty clubs in the shadow of the stadiums they once filled? Kerr and Burchill identify a typically self-aware adjustment as they raise the stakes to ensure reinvention. The songs they were playing, these now represented nothing less than their lives, the sum total of everything they had achieved as men and as a band – and that deserved the fullest commitment on stage, no matter how many tickets they sold. Redemption beckoned.

The film’s laser-like honesty slips a little in the final moments, which are devoted to fluffing the new line-up – at least until Kerr and Burchill have their closing say. As Kerr contemplates retirement and the need for a “good ending… a full stop”, Burchill counters by saying, “Aye… until the comeback”. Kerr’s currant-like eyes light up. The comeback after the comeback? “Very lucrative”, he chuckles. Don’t bet against them.