Love’s reputation rests on their dazzling third album, 1967’s Forever Changes. But the journey there involved several different stops. Not least among these is “She Comes In Colors” – a jazzier, flute and harpsichord-peppered Arthur Lee composition from 1966’s Da Capo. The Los Angeles band’s second album – named after a musical term meaning “back to the beginning” – took a pivotal step on the odyssey from their eponymous debut’s garage rock towards an ornate, psychedelic form of rock’n’roll.

Love’s reputation rests on their dazzling third album, 1967’s Forever Changes. But the journey there involved several different stops. Not least among these is “She Comes In Colors” – a jazzier, flute and harpsichord-peppered Arthur Lee composition from 1966’s Da Capo. The Los Angeles band’s second album – named after a musical term meaning “back to the beginning” – took a pivotal step on the odyssey from their eponymous debut’s garage rock towards an ornate, psychedelic form of rock’n’roll.

PINK FLOYD ARE ON THE COVER OF THE NEW UNCUT – ORDER YOUR COPY HERE

“The first album was more minimalist, with everything recorded live,” recalls guitarist Johnny Echols, sipping ginger beer on a tour bus in Leeds, shortly before performing the hallowed catalogue with The Love Band. “But Da Capo was a more grown-up album. We wanted to push the envelope. I’m very proud of ‘She Comes In Colors’, because we’d been known as a garage rock band but suddenly jazz musicians would come up to us and ask, ‘How on earth did you guys come up with that..?’”

The seeds of this adventure had been sown shortly before the main album sessions, when Love entered Sunset Sound Recorders’ Studio One with producer Jac Holzman and engineer Bruce Botnick to lay down “7 And 7 Is”, a hurtling proto-punk number that would become their first – and only – American Top 40 single (reaching No 33).

“That single was very different from the song Arthur had written,” says Echols, explaining that it had started out as “a kind of Dylanesque folk song about Arthur, very autobiographical”. As he explains it, an endorsement deal with Vox meant they could try out pioneering new effects, such as a tremolo box for a guitar and distortion pedal for the bass. “Which no-one had then. Arthur was listening in the booth and went, ‘That’s pretty cool.’” The results gave them the confidence to experiment even more, changing producers, studios and engineers for Da Capo and blossoming with “She Comes In Colors”. Receiving little airplay outside the LA area on release in 1966, the song wasn’t a hit but has had quite an afterlife. The Rolling Stones quoted it – “She comes in colours everywhere” – uncredited, in 1967 single “She’s A Rainbow”. The Hoosiers covered it and Janet Jackson sampled it. Even Madonna borrowed from it – unwittingly – on 1999 hit “Beautiful Stranger”, with producer William Orbit later admitting borrowing from the melody. “Arthur got a credit for that,” smiles Echols. “The whole group should have been credited really, but the acknowledgement was nice.”

JOHNNY ECHOLS: “My Little Book” had done quite well as a single [reaching US 52 in March 1966], so we wanted to keep pushing with “7 And 7 Is”.

BRUCE BOTNICK: It was just really, really unusual for me. I had never heard anything like that before. But I loved the energy. The drummer [Alban “Snoopy” Pfisterer, who’d trained as a pianist, not a percussionist] struggled with the tempo. After about 30 takes Arthur said, “Sit down, I’ll play.” I guess Snoopy must have then figured out how to do it.

ECHOLS: By that time everyone was cursing at the poor man. We played it so much that by the end my fingers were bleeding, but after that we felt we could do anything. We realised we needed a real drummer, so finally got Michael Stuart [now Stuart-Ware] from the Sons Of Adam.

MICHAEL STUART-WARE: Arthur had heard the Sons play a few times. One day, he came by our pad in Laurel Canyon and said, “You guys can have this tune if you want it”, and banged out “7 And 7 Is” on his black Gibson acoustic. Our lead guitarist Randy Holden said, “That’s not really us”, so Arthur played us “Feathered Fish”. Randy went, “We’ll take that!” and we covered it. Love’s original drummer, Don Conca, was fabulous, but the drugs took over and he stopped showing up for gigs. One night Arthur asked, “Is there a drummer in the house?” So Snoopy had filled in, but was more comfortable once he switched to harpsichord. Arthur was always asking me to join and after the Sons stopped getting along, I finally said OK. When I bumped into Don Conca he said, “That’s cool, man. You’re the only drummer in Hollywood who can handle it.”

ECHOLS: Don Conca was a loud showman, like Gene Krupa or Buddy Rich. Michael was a finesse drummer. He did these rhythmic counterpoints that sounded marvellous. We all had eclectic tastes. Country, gospel, blues, jazz. Arthur and I went to the same Memphis high school as Charles Lloyd and I’d watch fascinated as he played clarinet. After we moved to Los Angeles, Charles came to see Love at [LA club] Bido Lito’s. We were drawing 10 times more people than him. He was kinda miffed, but light-heartedly. When we wanted to go more jazzy we got Tjay Cantrelli, who we’d played with in the Grass Roots, on woodwind. He was just going to play a session, but the flute changed the sound so much that he became part of the group.

STUART-WARE: I’d listened to the first Love album, but Arthur wanted to cover new ground from a jazz foundation. At the first practice at Arthur and [guitarist] Bryan MacLean’s pad on Brier, we smoked hash and listened to Charles Lloyd, Cat Stevens and Fresh Cream. Then Arthur played his new tunes on the Gibson, including “She Comes In Colors”. On stage at Bido Lito’s, Love were a natural LSD trip with no comedown, but the new songs sounded more sophisticated.

ECHOLS: We also changed producers. Mr Holzman [also Elektra Records boss] came from a folk music background and wanted everything clean and pristine, but our sound was loud, levels driven into the red. When Jac told us about Paul Rothchild, who’d just got out of prison for selling marijuana, we thought that was the coolest thing. We hadn’t heard his stuff. The only reason we hired him was because he’d gotten out of prison. We also got a new engineer, Dave Hassinger, who captured our sound as it was and got a great mix. We went into RCA Studios, because Paul Rothchild was working with The Doors in Sunset. RCA had installed an eight-track machine, so we could overdub on Da Capo. It was a brand new slate. I think Paul Rothchild expected us to do something like the first album. It took him a while to get used to these jazzier songs, but then he got on board and he was perfect.

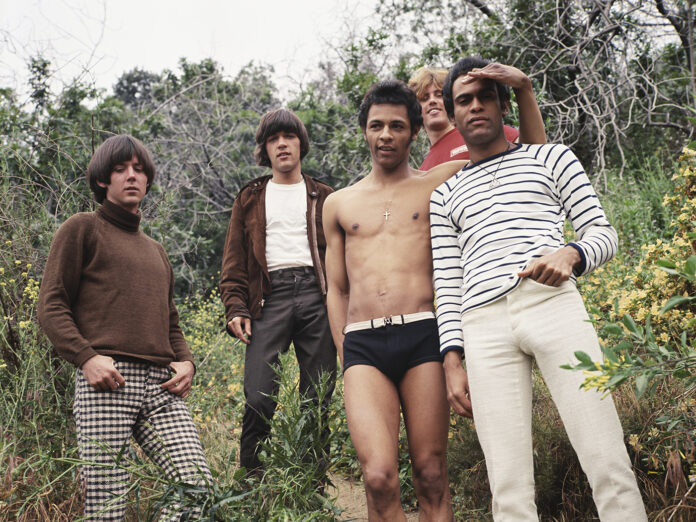

STUART-WARE: Love ruled the Sunset Strip mysteriously. Because the group didn’t play often, everyone was always, “Where are they?” Our racial diversity enhanced that mystique and was an integral part of our difference.

ECHOLS: We were a racially diverse hard rock group because Arthur and I were racially diverse and grew up in a racially diverse community. We wanted our group to reflect who we were. We didn’t want to be typecast as R&B, or play the Chitlin circuit, where Chuck Berry’s manager had to carry a 45 and say, “Pay me now

or he’s not going on.”

BOTNICK: It was highly unusual to have a black person doing rock’n’roll, before Hendrix, but Arthur never called any race issues. He dealt with you on the level of: “This is my music and this is what I want.”

ECHOLS: Arthur had taken accordion lessons and his parents had also bought him an organ. He only joined the band I had with Billy Preston in school because young ladies flocked to us. He had a musician’s soul but didn’t want to take the time to become one. His genius was to be able to sit down with a group of us and sing songs that he’d written, and as we’d find the chords he’d go, “I like that.” He assembled the music like a collage, in his head from what we played. “She Comes In Colors” was the most difficult song on Da Capo to record. It probably took seven or eight takes, because in a way it’s three songs in one, but it’s hard to hear where the changes are.

STUART-WARE: Playing unusual time signatures didn’t present much of a challenge for anyone in the group. I’d listened to Dave Brubeck in school and played in a high school jazz group. The jazzy groove on “She Comes In Colors” was one I had from the get-go. I just had to play harder because I was up against electronic instruments. The flute and harpsichord duet was groundbreaking, and Arthur’s vocal was diverse and immaculate, as always.

ECHOLS: Arthur was a showboat, an introspective child who’d found his thing by being different. In summer he’d wear a fur coat and one shoe, sweating in that coat so much it smelled. He had this idea that a rock person should be nutty, but he was a fantastic poet. Even in elementary school he was always writing little rhymes. He had the knack of taking the most mundane situation into something interesting, and you’d think, ‘Wow.’ He wrote “She Comes In Colors” about his girlfriend, Annette Bonan. She’s Annette Ferrell now, but always wore colourful clothes, like the flower children did then.

STUART-WARE: I never really knew what the songs were about. Arthur usually left it to the listener to work out the reality. If he was ever asked, self-deprecation was his blade of choice: “It’s just about some chick.” But maybe he did write that song for Annette.

ECHOLS: When Arthur sang “When I was in England town, the rain fell right down” he’d never been to the UK. I explained, “Arthur, it should be ‘London town’.” But he sang it anyway. Maybe he didn’t want to share songwriting credits, but people here think “England town” is kinda cute.

BOTNICK: By then Love should have been hugely successful, but Arthur wouldn’t tour, wouldn’t leave Hollywood. In those days to promote an act properly you had to play somewhere to get radio. I think he felt comfortable and safe in his environment, but not touring harmed their career.

STUART-WARE: Concert promoters would track me down by phone. I’d call Arthur and the answer was always no. Eventually he got mad at me for asking. I often wondered, ‘What’s with the not playing?’

ECHOLS: We played in New York, Vegas, or Massachusetts, but we couldn’t play in the South or middle America, or sometimes we’d have bookings cancelled. The problem was the racial makeup of the group. It hurt us, because The Doors and Buffalo Springfield and all those other groups were able to tour. But we were getting successful, buying houses and had women chasing us, whereas at the start we were just trying to make a living. Also, we did some dumb things. I’ll demonstrate the mindset of a rock’n’roll kid. I bought an E-Type Jaguar, and when it ran out of gas I left it at the side of the street. My father begged me to go back for it. Eventually it was impounded and auctioned. Those cars are worth hundreds of thousands now. Leaving my car was probably the dumbest thing I ever did, along with insisting that Elektra sign The Doors. We got a fantastic offer from MCA Records, who could get us into way more shops, but we knew that having Love on their label was part of Elektra’s cachet. We figured that if they had The Doors, maybe they’d let us go. But instead all the money that was going to promote Love went on The Doors. People went “What did you do that for?” Because we were dumb kids! I was barely 18 then.

STUART-WARE: Then The Rolling Stones stole the line “She comes in colours” for “She’s A Rainbow”. Wasn’t Mick [Jagger] afraid of being sued? I remember we all thought, ‘Wow. How could Mick think it was OK to do that?’

BOTNICK: We all take stuff, but I do remember Arthur being offended.

ECHOLS: When Madonna used the melody from “She Comes In Colors” for “Beautiful Stranger”, Arthur was credited as a writer.

STUART-WARE: It doesn’t bother me that neither Da Capo or Forever Changes were hugely successful. What does bother me is that we didn’t work harder to promote both albums, or play more shows just for the thrill of playing.

ECHOLS: But even though Da Capo didn’t sell a whole lot, we felt we’d arrived as a group. People like The Beach Boys were talking to us as peers. On the next album we felt we had to push it to another higher level. The universe smiled on us, we did Forever Changes, and in the 55 years since it’s never been out of print.

The Love band featuring Johnny Echols tour the UK in July – tickets can be found here

Michael Stuart-Ware’s Love book, Behind The Scenes At The Pegasus Carousel, is now available as a Kindle under the title Pegasus Continuum