A second chance to go wild about Harry... While the stoned and tie-dyed hordes were overrunning the West Coast during 1967’s Summer Of Love, Harry Nilsson was holed up in Hollywood’s RCA Studios with Jefferson Airplane producer Rick Jarrard and an assortment of top LA session musicians working on his debut album. The 26-year-old was one of an elite coterie of literate, relatively short-haired iconoclasts that included Randy Newman and Van Dyke Parks. These were the true radicals of the era, beholden to no trends or movements, each conjuring up his own visionary world while simultaneously keeping alive the values and conventions of American musical tradition from Stephen Foster to Tin Pan Alley. But even among these buttoned-down renegades, Nilsson stood apart, with his three-and-a-half octave vocal range and childlike sense of wonder, his refusal to be ingested into any genre or to perform in public. This studio rat was rock’s Wizard Of Oz, enchanting listeners from behind a shroud of mystery. He comes into focus as never before on The RCA Albums Collection, which contains the 14 LPs he recorded for the label between 1967 and ’77 in accurate reproductions of their original sleeves, adding 123 bonus tracks, 55 of them previously unissued, the whole of it filling 17 discs. That first album, Pandemonium Shadow Show, and the two that followed, 1968’s Aerial Ballet – containing his first hit, a shimmering cover of Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin’” that was memorably used in the film Midnight Cowboy, along with his signature song “One” – and 1969’s Harry, form a pop trilogy as facile, melodious and inviting as the early works of McCartney and Elton John, while predating both by several years. Listening now to his wildly clever Beatles medley titled “You Can’t Do That” on the first album, followed two songs later by a spot-on cover of “She’s Leaving Home”, it’s easy to see why John and Paul named Nilsson as their favourite artist and favourite band during a 1968 press conference. He then threw three straight change-ups – Nilsson Sings Newman, his exquisite LP of Randy Newman songs, with Newman accompanying him on piano; the resolutely whimsical soundtrack to his animated TV movie The Point!; and Aerial Pandemonium Ballet, a radical reimagining of his first two albums – before aiming his next pitch right down the middle. For Nilsson Schmilsson, he cannily turned to commercially successful producer Richard Perry, resulting in his best-selling album and lone chart-topping single, a nearly operatic rendering of Badfinger’s “Without You”. Schmilsson streamlined the qualities of his earlier records, presenting them more directly, alternately appealing to the listener’s heart (“I’ll Never Leave You”), head (“Gotta Get Up”), sense of rhythm (“Jump Into The Fire”), sense of whimsy (“The Moonbeam Song”) and funny bone (“Coconut”). But on 1972’s Son Of Schmilsson, the follow-up to his biggest commercial success, he began the pattern of self-sabotage that beset his later work in what some critics saw as an act of self-loathing, like a petulant child carefully making a series of drawings, only to scribble all over them. The abrupt shift in tone and intent was exemplified by the refrain of “You’re Breakin’ My Heart” (“…so fuck you”) and the close-mic’d belch that opens the kickass rocker “At My Front Door”. To be sure, the LP has its share of Nilsson’s trademark romantic/ironic refinement, including the gorgeously elegiac “Remember (Christmas)” and the Newman-like ballad “Turn On Your Radio”, but bad-boy humour and hardcore cynicism drive most of the songs and performances. The change transformed Nilsson almost at once from a major recording artist into an oddity – a sideshow to the main stage of popular music. A Little Touch Of Schmilsson In The Night (1973) – his sublime album of standards, arranged by Sinatra stalwart Gordon Jenkins and produced by Nilsson’s Beatles connection Derek Taylor – gave way to the confused, largely abrasive Lennon-produced collaboration Pussy Cats, recorded during the ex-Beatle’s 18-month “lost weekend” in LA, his once-angelic voice sounding ravaged by the abuse he put it through. Then came Duit On Mon Dei, an album’s worth of largely uninspired originals, which arranger Van Dyke Parks ornamented with the requisite marimbas and steel drums. Two more wayward and maddeningly self-indulgent albums in Sandman (1975) and …That’s The Way It Is (1976) followed. Owing RCA one more album, Nilsson pulled himself together, reined in his latter-day tendency to go off the deep end lyrically and vocally, and made the most accessible, least off-putting LP since Schmilsson. Knnillssonn’s 10 songs were self-written, their keys comfortably in his mid-range where the vocal damage was less apparent, the arrangements centred on elegant strings. The overtly romantic “All I Think About Is You”, the achingly candid “I Never Thought I’d Get This Lonely”, the big-hearted, irony-free “Perfect Day”, were genuinely beautiful, and he sang them with the understated sophistication he’d perversely abandoned four years earlier. But this inviting, sophisticated and redeeming record appeared too late for RCA, for the fans he’d let down and for his career as a whole, the wayward years in effect eradicating the collective memory of the great ones. Nilsson died of a massive heart attack in 1994 at the age of 54, having recorded nothing of note after leaving RCA. But he left an enormous amount of music in those 10 years, the bulk of it gathered in this much-needed career overview of the forgotten solipsistic genius of rock’s golden age, in which the strike-outs turn out to be as fascinating as the home runs. Extras: Demos, alternate takes, single mixes, outtakes, mono versions, Italian-language versions, studio banter, radio spots. Bud Scoppa Photo credit: Tom Hanley

A second chance to go wild about Harry…

While the stoned and tie-dyed hordes were overrunning the West Coast during 1967’s Summer Of Love, Harry Nilsson was holed up in Hollywood’s RCA Studios with Jefferson Airplane producer Rick Jarrard and an assortment of top LA session musicians working on his debut album. The 26-year-old was one of an elite coterie of literate, relatively short-haired iconoclasts that included Randy Newman and Van Dyke Parks.

These were the true radicals of the era, beholden to no trends or movements, each conjuring up his own visionary world while simultaneously keeping alive the values and conventions of American musical tradition from Stephen Foster to Tin Pan Alley. But even among these buttoned-down renegades, Nilsson stood apart, with his three-and-a-half octave vocal range and childlike sense of wonder, his refusal to be ingested into any genre or to perform in public. This studio rat was rock’s Wizard Of Oz, enchanting listeners from behind a shroud of mystery. He comes into focus as never before on The RCA Albums Collection, which contains the 14 LPs he recorded for the label between 1967 and ’77 in accurate reproductions of their original sleeves, adding 123 bonus tracks, 55 of them previously unissued, the whole of it filling 17 discs.

That first album, Pandemonium Shadow Show, and the two that followed, 1968’s Aerial Ballet – containing his first hit, a shimmering cover of Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin’” that was memorably used in the film Midnight Cowboy, along with his signature song “One” – and 1969’s Harry, form a pop trilogy as facile, melodious and inviting as the early works of McCartney and Elton John, while predating both by several years. Listening now to his wildly clever Beatles medley titled “You Can’t Do That” on the first album, followed two songs later by a spot-on cover of “She’s Leaving Home”, it’s easy to see why John and Paul named Nilsson as their favourite artist and favourite band during a 1968 press conference.

He then threw three straight change-ups – Nilsson Sings Newman, his exquisite LP of Randy Newman songs, with Newman accompanying him on piano; the resolutely whimsical soundtrack to his animated TV movie The Point!; and Aerial Pandemonium Ballet, a radical reimagining of his first two albums – before aiming his next pitch right down the middle. For Nilsson Schmilsson, he cannily turned to commercially successful producer Richard Perry, resulting in his best-selling album and lone chart-topping single, a nearly operatic rendering of Badfinger’s “Without You”. Schmilsson streamlined the qualities of his earlier records, presenting them more directly, alternately appealing to the listener’s heart (“I’ll Never Leave You”), head (“Gotta Get Up”), sense of rhythm (“Jump Into The Fire”), sense of whimsy (“The Moonbeam Song”) and funny bone (“Coconut”).

But on 1972’s Son Of Schmilsson, the follow-up to his biggest commercial success, he began the pattern of self-sabotage that beset his later work in what some critics saw as an act of self-loathing, like a petulant child carefully making a series of drawings, only to scribble all over them. The abrupt shift in tone and intent was exemplified by the refrain of “You’re Breakin’ My Heart” (“…so fuck you”) and the close-mic’d belch that opens the kickass rocker “At My Front Door”. To be sure, the LP has its share of Nilsson’s trademark romantic/ironic refinement, including the gorgeously elegiac “Remember (Christmas)” and the Newman-like ballad “Turn On Your Radio”, but bad-boy humour and hardcore cynicism drive most of the songs and performances. The change transformed Nilsson almost at once from a major recording artist into an oddity – a sideshow to the main stage of popular music.

A Little Touch Of Schmilsson In The Night (1973) – his sublime album of standards, arranged by Sinatra stalwart Gordon Jenkins and produced by Nilsson’s Beatles connection Derek Taylor – gave way to the confused, largely abrasive Lennon-produced collaboration Pussy Cats, recorded during the ex-Beatle’s 18-month “lost weekend” in LA, his once-angelic voice sounding ravaged by the abuse he put it through. Then came Duit On Mon Dei, an album’s worth of largely uninspired originals, which arranger Van Dyke Parks ornamented with the requisite marimbas and steel drums.

Two more wayward and maddeningly self-indulgent albums in Sandman (1975) and …That’s The Way It Is (1976) followed. Owing RCA one more album, Nilsson pulled himself together, reined in his latter-day tendency to go off the deep end lyrically and vocally, and made the most accessible, least off-putting LP since Schmilsson. Knnillssonn’s 10 songs were self-written, their keys comfortably in his mid-range where the vocal damage was less apparent, the arrangements centred on elegant strings. The overtly romantic “All I Think About Is You”, the achingly candid “I Never Thought I’d Get This Lonely”, the big-hearted, irony-free “Perfect Day”, were genuinely beautiful, and he sang them with the understated sophistication he’d perversely abandoned four years earlier. But this inviting, sophisticated and redeeming record appeared too late for RCA, for the fans he’d let down and for his career as a whole, the wayward years in effect eradicating the collective memory of the great ones.

Nilsson died of a massive heart attack in 1994 at the age of 54, having recorded nothing of note after leaving RCA. But he left an enormous amount of music in those 10 years, the bulk of it gathered in this much-needed career overview of the forgotten solipsistic genius of rock’s golden age, in which the strike-outs turn out to be as fascinating as the home runs.

Extras: Demos, alternate takes, single mixes, outtakes, mono versions, Italian-language versions, studio banter, radio spots.

Bud Scoppa

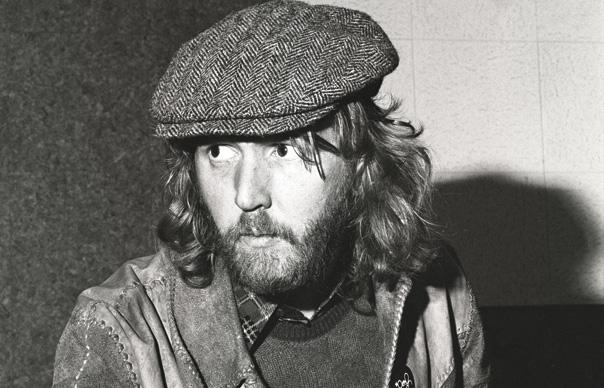

Photo credit: Tom Hanley