The rebirth of Richard Alpert is one you can imagine George Harrison being more than a little envious of. Born in Boston, Alpert was an associate of Timothy Leary and deeply entrenched in the American psychedelic counterculture of the ’60s, until he returned after a protracted stay in India reinvented as Ram Dass, a spiritual guru set on popularising eastern teachings in the west.

The rebirth of Richard Alpert is one you can imagine George Harrison being more than a little envious of. Born in Boston, Alpert was an associate of Timothy Leary and deeply entrenched in the American psychedelic counterculture of the ’60s, until he returned after a protracted stay in India reinvented as Ram Dass, a spiritual guru set on popularising eastern teachings in the west.

Harrison, however, was a Beatle and a star, and no-one was going to let him forget it. Around the time he wrote and recorded his second proper solo album, 1973’s Living In The Material World, he was being pulled between two poles; on one hand, he was deeply exploring spirituality and continuing the inner journey that had begun in his early twenties, but on the other, having to deal with that material world of Beatles-related lawsuits, the first wave of the “My Sweet Lord” copyright infringement case and interminable struggles to get the funds from his pioneering Concert For Bangladesh to the people who needed them.

Consisting almost entirely of brand new tracks, in contrast to 1970’s anthological All Things Must Pass, Living In The Material World perfectly reflects the duality of Harrison’s life at the time. There is devotional material, such as the power-pop delight of “Don’t Let Me Wait Too Long” and the lilting “Give Me Love (Give Me Peace On Earth)”, sometimes disguised as songs of love to a partner rather than to God. There are songs set purely in the secular world, most notably the exotic R&B of “Sue Me, Sue You Blues”, a bitterly hilarious chronicle of the Fabs’ legal machinations, very much a descendant of “Taxman”.

Many of the other songs are a mix of the two, with Harrison’s trudge towards salvation slowed by petty annoyances – if the material world would only go away and leave him alone, as he pleaded in “Don’t Bother Me”, all those lifetimes ago, then he could reach nirvana. So the grand, baroque “The Light That Has Lighted The World” – the musical essence of “Isn’t It A Pity?” condensed and concentrated – calls out those “hateful” people who misunderstand him and his beliefs, while “The Day The World Gets ’Round” laments “such foolishness in man” and praises the “few who bow before you/In silence, they pray…”

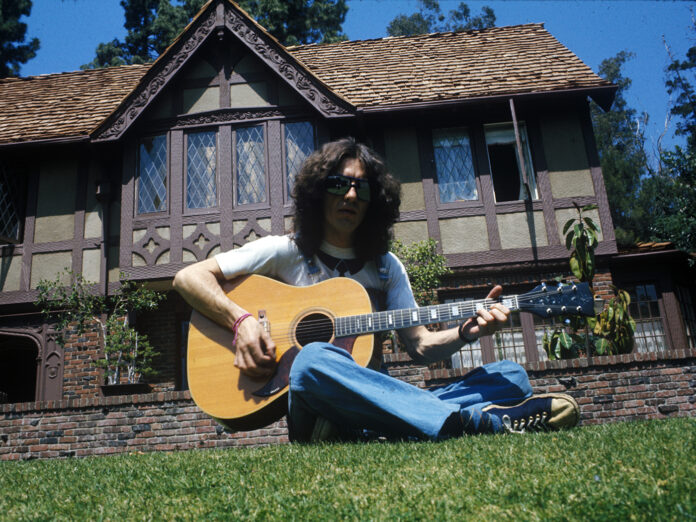

Po-faced? Pretentious? Looking at “this sad world and all the hate” in 2024, you might be stirred to say that Harrison was indeed correct about the paltry grievances that are still causing wars, and wise about the greed and ignorance that continue to poison. If a little enlightenment still wouldn’t go amiss, then two of the album’s finest songs might provide a guide. “Be Here Now”, named after Ram Dass’s first book, is a spectral, droning dirge with some of Harrison’s greatest, sourest chord changes, entreating us to “remember/Be here now… the past was/Be here now”, while “That Is All” ends the record on a hopeful note, Harrison hymning his love to the world over a beautiful, amorphous ballad, like “Something” dissolving in mountain mist.

With strings and the odd choir, this is still an epic-sounding album, but it’s far more stripped-back than All Things Must Pass, and recorded primarily at Harrison’s own Friar Park home studio with a small core of musicians. Harrison takes on all the guitar duties himself this time, including some stunning slide guitar solos and chiming 12-string acoustic work, while there are prominent keys from Nicky Hopkins, and occasional, slightly glam double drumming from Ringo and Jim Keltner. In Phil Spector’s ethanolic absence, Harrison produced himself, and this new 2024 remix by Paul Hicks and Dhani Harrison brings the album into greater relief when compared to previous releases: the orchestral arrangements are brought out of the murk, Harrison’s vocals are clearer and sharper, and the album’s peculiar air of dry, ascetic starkness is increased. The loudest moments, from the wry boogie of the title track to the soulful, rootsy “The Lord Loves The One (Who Loves The Lord)”, are funkier and more present, as if a veil has been lifted.

As well as a book and copious notes, depending on the edition, this 50th anniversary set comes with an album of alternate versions, not as revelatory as the extra tracks on the 50th box of All Things Must Pass but still with insights to impart. The complex rhythms of “Sue Me…” were pretty much sorted from the start, it seems, but it’s thrilling to hear early takes of “The Light…” and “The Lord Loves The One…”. “Be Here Now”, seemingly a later take than the final chosen one, shows just how much Harrison and his musicians changed their parts on the fly in the studio. Alongside B-side “Miss O’Dell”, there’s also an unearthed, fleet-footed version of the joyful “Sunshine Life For Me (Sail Away Raymond)”, recorded with Harrison’s heroes The Band (the song appeared with Starr’s vocals on November ’73’s Ringo).

Watch the video for “Sunshine Life For Me (Sail Away Raymond)”

When stripped of their orchestral and choral sweetening, Living In The Material World’s big ballads feel even more soul-baring. Rather than being driven by a holier-than-thou smugness, this is an album whose wracked, painful honesty and sense of deep disappointment rivals that of John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band. Harrison had attained the wealth, power and adoration that billions dream of and found it lacking, yet he’d glimpsed an alternative. “Got a lot of work to do/Try to get a message through,” he sang on the title track, a man desperately reaching for a chink of light in the gloom of The Beatles’ shadow.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.